All posts reviewing Nathanael Vette’s Writing With Scripture are archived at Vette : Writing With Scripture

With thanks to T&T Clark who forwarded me a review copy.

The claim that the scriptural character of early Christian narrative illustrates its non-historical character is one conservative exegetes have been anxious to dismiss and radical exegetes have been eager to embrace. For conservative exegetes, the scriptural language of the Gospel narratives always has its basis in ‘fact’.

. . . .

Radical exegetes, on the other hand, begin by assuming the non-historical character of the Gospels. On this basis, anything and everything can be seen to have a scriptural origin.

. . . .

Both are remarkably confident about the ability of scholarship to uncover the historical details behind the Gospels, in their presence or their absence. Both affirm that the scriptural character of the Gospels has its basis in either ‘fact’ or ‘fabrication’ . . . . . Given the choice between ‘history remembered’ and ‘prophecy historicized’, the exegete will inevitably choose whichever confirms their presuppositions. (NV, 199f)

Those words, extracted from the opening pages of the concluding chapter of Nathanael Vette’s Writing With Scripture, indicate to me, an outsider, that the study of Christian origins through the Gospels is fundamentally about faith, belief, or challenges to faith and belief than about historical research as it is understood and practised in History Departments and Faculties. Note the words “anxious”, “eager”, and “remarkably confident”. Those words describe an emotional commitment. Note the terms “begin by assuming” and “confirms their presuppositions”. Those words point toward a flawed methodology that I will address below.

Mark Goodacre’s mid-way position between conservatives and radicals, as I understand it through NV’s discussion, posits that each “story unit” (or pericope) in the Gospels should be assessed in its own right for whether or not we might reasonably conclude that it derives from a prior source of some kind, whether that source be historical memory or some kind of legendary tale. So when we read an episode in the Gospels that borrows terminology from Scriptures, instead of concluding that we are reading either history that happened to coincide with words of Scripture or fiction composed entirely out of Scripture, we would do better to infer that we are reading “tradition scripturalized”. But this is the same flawed methodology simply working from different assumptions.

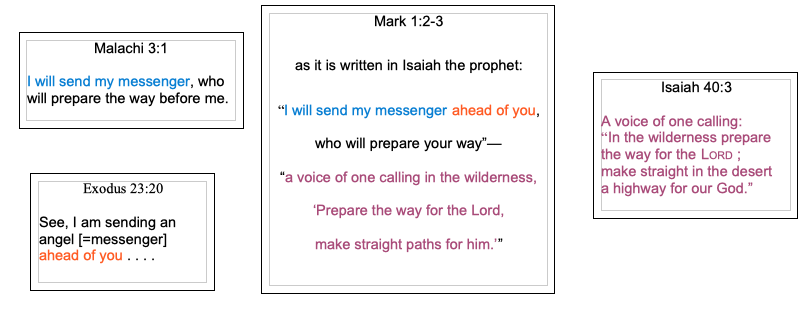

NV goes “one step further” than Goodacre:

But this analysis can go one step further: scripturalization can also describe the literary process by which Mark as an author used scriptural elements to compose and model episodes in their life of Jesus, creating scripturalized narrative. That Mark used the Jewish scriptures in this way depends in large part on whether this practice can be identified in other works from the period. If it can be shown across a diverse group of texts that the Jewish scriptures were regularly used to compose new narrative, then it would be appropriate to speak of scripturalized narrative as a stylistic feature of Second Temple literature. (NV, 29)

At the end of his study NV concludes:

We found that scripturalized narratives usually have their basis in some underlying tradition. This is seen most clearly in those episodes which relate to a scriptural figure or episode. At one end, scripturalized narratives can result from a close and profound exegetical engagement with their source: by narrating Gen. 9:1-7 in the language of Genesis 13 and 15, the Genesis Apocryphon ties the Abrahamic covenant to the Noachide covenant (part 3). At the other end, long and complicated narratives can be triggered by a single word – i.e. the two fiery furnaces of Pseudo-Philo or simply reflect the similarity of one figure with another – i.e. Abraham with Job in the Testament of Abraham (part 4). Whilst it is possible for a figure to be pieced together entirely out of scriptural material for no perceptible reason – i.e. Pseudo-Philo’s Kenaz and Zebul (part 2) – this is the exception not the norm. In most cases, the compositional use of scriptural elements in scripturalized narratives has been triggered by some aspect of the source text or tradition. (NV, 201)

The Methodological Flaw

Continue reading ““Some Underlying Tradition” — a review of Writing With Scripture, part 10″