Couchoud thought that John the Baptist epitomized and popularized the Jewish hopes for a coming Judge from Heaven — as shown in my previous post in this series (the entire series is archived here).

Christianity was born of the travail of the days of John. The Baptist gave it two talismans with which to bind souls:

- the advent of the Heavenly Man in a universal cataclysm,

- and the rite of baptism which allowed the initiates to await, without apprehension, the Coming of the Judge.

(p. 31, my formatting)

At first the teaching spread like wildfire but without John’s name attached to it as its IP owner.

Before long the teaching became enriched with various kinds of additions. First among these additions were new names for the Heavenly Man: Lord, Christ, Jesus.

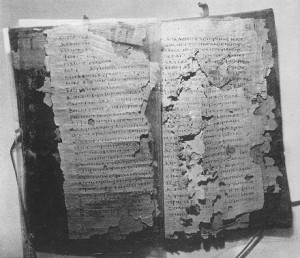

Lord as a title was derived from Psalm 110:1

The Lord said unto my Lord,

Sit thou at my right hand,

Until I make thine enemies thy footstool.

To whom could this have been addressed? Surely not to the Messiah, the Son of David, waited for by the Pharisees. David would not have called his son “my Lord.” It must have been to the Son of Man who, according to the Revelation of Enoch, was placed on the throne of his glory by God Himself. (p. 31)

Since David as an inspired prophet makes it clear that the Son of Man is enthroned at the right hand of God and calls him Lord. So believers could also call the Son of Man their Lord.

(Note that the title “Son of Man” was used as a Greek expression, too. Think of Christianity as moulded very largely by Greek speakers.)

Christ, Christos, “is a somewhat barbarous translation of the Hebrew word which means consecrated by unction, Messiah.” Continue reading “The First Signs of Christianity: Couchoud continued”