I was about to start the next post in my series attempting to justify seriously questioning the “bedrock fact” status of the crucifixion of Jesus when I came across a new publication by Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan, The First Paul: Reclaiming the Radical Visionary Behind the Church’s Conservative Icon.

There are some interesting enlightening details in it, and, (sorry to say, but Borg and Crossan are big enough to take and deserve it) some incredible howlers of both method and conclusions that I would never have expected in a work by scholars of such high repute. Maybe this is because they were leaning more to accessing a popular reading public than the scholarly guild with this one. I am reminded of earlier posts where I have expressed some disgust against scholars who know better yet see fit to short change their popular readership like this. For my most recent protest, see my remarks on Pagels and King in A Spectrum of Jesus Mythicists and Mythers. I’ll address one of these lower high school level howlers in a future post. But first, something good and interesting from the book. (Anyway, I guess that’s one of the reasons for my blog — to attempt to make a bit more accessible some of the thinking of scholars on these sorts of topics.)

On page 127 they write:

For many centuries, the death of Jesus has been understood by most Christians as a substitutionary sacrifice for sin, as a substitutionary atonement, as this theological understanding is called.

This way of seeing the death of Jesus is very familiar. Most Christians today, and most non-Christians who have heard anything about Christianity, think that the cross means, in slight variations:

Jesus died for our sins.

Jesus is the sacrifice for sin.

Jesus died in our place.

Jesus is the payment for sin.

For this understanding, the notions of punishment, substitution, and payment are central. We deserve to be punished by God for our sins, but Jesus was the substitute who paid the price. The issue is how we may be forgiven by God for our sin and guilt.

Then follows what must be a bombshell for most fundamentalists in particular:

But this understanding is less than a thousand years old. (p.128)

So where did it come from?

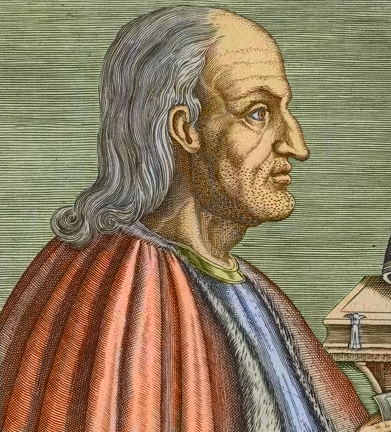

Borg and Crossan answer: It came from a theological treatise, Cur Deus Homo? = Why Did God Become Human? by Anselm of Canterbury, first published in 1097.

This is Anselm’s argument:

- All people have disobeyed God. So all people are sinners.

- Someone has to pay for our sin. Forgiveness means that compensation must be made for the offence or crime. If no payment was required for sin, then it would imply God does not think is anything very important.

- Since God is infinite, our debt to him is also infinite. But we are finite, so are incapable of paying the price owed.

- Jesus is infinite, and when he became human he could pay the full cost of the penalty for us as a substitute sacrifice. So we can be forgiven.

And this has been the understanding of Christianity in general ever since! Well, I never knew that! Just Kipling Just So story, only it’s probably true! 😉

Mel Gibson and his “patron pope”, John-Paul II who apparently loved his The Passion of the Christ movie, have both preached the same Anselm Cur Deus Homo? doctrine.