Anyone who suspects graphic details in a narrative are a sign of authenticity of a text or eye-witness source needs to read Anthony Grafton’s Forgers and Critics : Creativity and Duplicity in Western Scholarship (1990). In this blog post I’m sharing my notes from his first chapter.

According to Anthony Grafton, there are two claims that remind readers of the possibility of forgery at work:

According to Anthony Grafton, there are two claims that remind readers of the possibility of forgery at work:

- the claim that a writer had copied accurately every word of the ancient texts before him (how could readers know? is the assertion intended to put readers off the scent of something suspicious?)

- the claim that a document was found in miraculous or extremely lucky circumstances (e.g. the High Priest Hilkiah just happened to find in the Temple for King Josiah the Book of Deuteronomy that had eluded all priests before him; Egyptian medical texts claim to have been found “under the feet of Anubis”, etc. — see my notes on Davies’ discussion of the Book of Deuteronomy re the book’s fraudulent provenance.)

Greece, 6th and 5th centuries b.c.e.

Solon and Pisistratus, Athenian statesmen, were suspected of interpolating lines into Homer’s Iliad to give Athens a more prominent role in the Trojan War than Homer had originally given that city.

Acusilaus of Argos, author of an account of gods, demigods and human heroes, claimed his source of information was a set of “bronze tablets discovered by his father in their garden.”

He thereby created one of the great topoi of Western forgery, the motif of the object found in an inaccessible place, then copied, and now lost, as the authority for what would have lacked credibility as the work of an individual. (p.9)

Ctesias, an historian who wrote a gossipy account of Persian history that regularly contradicted another famous historian, Herodotus, claimed to have superior sources. He claimed he had accessed and read the official archives of Susa.

He thereby enriched forgers with another of their favourite resources, the claim to have consulted far-off official documents, preferably in an obscure language.

Greece, 5th and 4th centuries b.c.e.

Public inscriptions declaring the rights and possessions of cities, and producing documentary evidence to support these claims, sprang up during an era of city-state rivalries.

Antiquaries compiled from local tradition, logical inference, and thin air full lists of their cities’ early rulers, their temples’ early priestesses, and their games’ early victors.

When such claims could be supported with a bit of padding out from details of ancient treaties and other documents, historians and orators would come to the rescue and find just the texts they needed to publicly quote in the inscriptions.

Temples were also in rivalry with one another, so the more records that could be “found” that supposedly demonstrated that gods themselves had visited them in the past, or that miraculous cures had been performed by their gods, the better. To meet the need appropriate historical inscriptions were found, and so were relics discovered that “proved” the cures.

The Peace of Mid 5th century b.c.e., the Greek Battle of Marathon hero, Callias, was sent to Persia to conclude a peace treaty. During the 4th century the stone monument claiming to be this peace treaty came under question. Suspicions were aroused by Theopompus who noticed that the script it was carved in, the Ionian alphabet, had never been used by the Athenians until the end of the 5th century. Anachronisms thus made their appearance as a tool for detecting forgeries.

Why the historian Thucydides preferred Oral Testimony. Thucydides is famous well known for asserting that direct oral testimony was always to be preferred by an historian to written testimony. This suggests, of course, that written records could not be interrogated and established in the same way oral reports could.

The irony here is that Richard Bauckham in his “Jesus and the Eyewitnesses” uses this claim of Thucydides to assert that ancient historians (pre-Enlightenment characters) used more reliable evidence than (post-Enlightenment) moderns, and writes of “eyewitness testimony” as if it were something holy, unquestionable, raw experience — and writes at length about the “testimony” of holocaust survivors. So it is interesting to read Grafton’s take on Thucydides’ method here: written testimony could not be questioned the way oral testimony could. I can’t imagine Bauckham seriously suggesting that the gospel authors spent time “interrogating” their eye-witnesses.

The Literary, Library and Book market revolutions

By the fourth century b.c.e. educated people were aware that literary works by specific individuals carried distinctive styles and sets of concerns.

Canons of classic texts began to emerge as exemplars of the best in prose and poetry. Schools taught pupils to imitate these. A favourite school exercise was to give students an assignment of writing letters in the style of, and expressing the interests of, well-known authors. Some of these could easily have become accepted as genuine once they went into circulation.

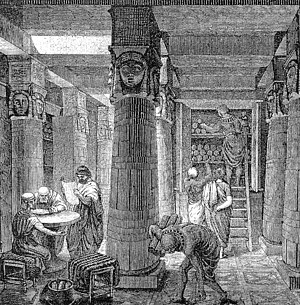

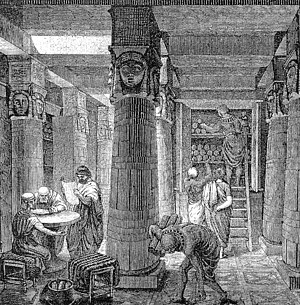

According to Galen, the demand for texts from the literary masters in the canons soon outgrew supply. Libraries, schools, and wealthy individuals sought new and old works at great expense. Forgers produced hitherto unknown works (supposedly) by famous authors and sold those to the major libraries as well.

At public orations and dramatic performances audiences would as likely as not be being treated to forgeries. (p. 12) The famous names sold.

Libraries contained multiple copies of works by the famous playwrights Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, and prose works by Plato, Hippocrates and Aristotle, but many of the titles attached to these names were outright forgeries.

Librarians reacted by compiling lists of what they judged to be genuine works in their collection, and others judged as spurious. Librarians and literary scholars devised various tests to attempt to determine which works were genuine and which spurious.

So, for example, at a time when there were 130 plays in circulation claiming to be by the playwright Plautus, scholars such as Varro judged only twenty or so to be genuine.

Sectarian rivalries to prove the greatest antiquity

Orphic and Pythagorean sects. Members of groups or sects such as these chose to live by authoritative texts of their so-called founding masters who had supposedly lived in distant antiquity.

The need for ancient texts by such groups was met by those willing to make the effort to supply it.

Egyptian, Babylonian and Jewish pride produces more “proof texts”. After being conquered by Alexander the Great and ruled by Greek dynasties, scribes and priests from these peoples restored some of their cultural pride by managing to prove that their histories and famous texts showed that they were older and more prestigious in literary, philosophical and religious accomplishments than the Greeks.

These “proof texts” were meant to impress a Greek audience since they were written in Greek, although they claimed to have been translations of earlier texts.

The Jews, for example, produced a Greek version of the Bible, although they claimed it was a translation of an earlier Hebrew one. They went further, however. They also claimed that their Hebrew Bible was the very source of inspiration for those famous Greek philosophical ideas of Plato etc.

Epicurean, Pythagorean and Zoroastrian sects, not to be outdone, had to offer texts that could claim the same or greater antiquity than the Middle Eastern ones.

How to create a text with the glamour of divine authority

- It must appear to come from a respectfully distant historical past

- It could be written in the first person as if spoken by either

- a divine figure

- or one of his human companions

- or an authoritative interpreter of his teachings

- It should (unlike “normal” literary genres) preferably offer a variety of functions, instructing in both methods of worship and daily life conduct

Forgeries of this kind abounded, and the methods used to detect them grew in sophistication as the complexity of the forgeries became ever more baroque. (p. 15)

Not questioned by Grafton, but surely entitled to the question, is the traditional scholarly dating of the Pauline epistles and the canonical gospels. Scholars who rely on internal evidence only to say that Paul wrote in the 50’s or the gospels were written not long after 70 c.e. seem to me to be leaving the door wide open for the trap Grafton warns against here. Surely external evidence — when we can see OTHERS first knew of these texts — should surely carry much more weight than it currently does. But to be this careful, it would mean ascribing the letters of Paul — and all the gospels — to the second century! Oh no – impossible – . . . . That would change EVERYTHING! Yup! Especially if we can see how they so conveniently met the “timely needs” of those others! Whoops . . . .

A sophisticated forgery classic: the Letter of Aristeas

Date: probably 2nd century b.c.e.

Purpose: To explain the origin of the Greek version of the Old Testament or Jewish Bible, the Septuagint, the LXX.

Contents:

- The librarian of the Egyptian Alexandrian library, Demetrius, writes to his king Ptolemy Philadelphus “about acquisitions policy”. He points out that the library lacks a copy of the “Books of the Laws of the Jews”, and that the only extant ones are in Hebrew and of inferior quality since they have not had royal warrant to guarantee their accurate transmission.

- The king responds giving Demetrius permission to ask the Jewish high priest, Eleazar, to send 6 representatives from each of the twelve tribes of Israel “to prepare a perfect, official translation.”

- The letter defends the ritual codes of the Jews in the Law, explaining that these are all allegories for deeper philosophical conduct and are not meant to be interpreted literally. The ethical standards of the Book are praised.

- The letter concludes with the acceptance of the new translation by all the Jews at Alexandria.

Evidence of forgery:

The Demetrius in question was never the librarian of the Alexandrian library under Ptolemy Philadelphus (who disliked him). Grafton cites Pfeiffer, History, 100-101 for other errors as well, but I have not yet had a chance to consult this.

Sophistication of the lie:

The author uses the methods that Alexandrian critics had developed to correct texts and detect fakes to make his own text seem all the more credible.

Example:

- he uses the allegorical method to “explain away” or justify the crude dietary and other ritualistic codes of the Jews just as other contemporary scholars had used allegory to rationalize the more barbaric and tasteless sections of Homer.

- he discusses how the correct translations were arrived at in part through standard textual criticism — collating all the variant manuscripts and emendations available — to suggest the most scholarly methods of determining accuracy were used and to strengthen the credibility of his narrative

- rather than just tell a narrative story about the negotiations between Demetrius and Ptolemy, he “quotes word for word” from Demetrius’ memorandum. Adding a touch of realism like this (a lie within a lie) enhances the credibility of his letter.

- he writes for two audiences: for Jews of Palestine to demonstrate that the Greek translation is superior to their Hebrew version; for gentiles to demonstrate that the Jewish ritual laws are not meaningless but allegorical philosophical codes.

- his motive is not money, but a desire to assert the spiritual authority of the Septuagint over the Hebrew bible.

Grafton comments that this forgery is one of the most complex to survive, but it is really but one example of a very large population. “The early Christians produced them by the dozen” (p.17)

Christian forgeries

Scholars have long recognized that 1 and 2 Timothy, and Titus, are forgeries, just as much as the Apostolic Constitutions. Their intent, of course, was to use the names of old authorities, and first-person accounts, to attempt to settle doctrinal disputes within the church.

The more exotic the claimed origin, and language, the better

Publics could be more impressed if a document could be said to have originated in a foreign (holy — e.g. Egyptian, Etruscan) language, with an explanation that its Greek translation could only partially capture the full power of the original.

This was the case with the text of the demigod Hermes Trismegistus, which was in fact written in Greek for Greek reader, despite its claim to have had an Egyptian origin. It still impresses some people today, although it was originally a pastiche of Greek philosophical tags and poorly understood Egyptian sayings and traditions — but it seemed exotic and appeared to have had an Egyptian origin.

Another case was the “thunder calendars” of supposedly Etruscan origin. These explained the meanings of thunder on any given day of the year. The text claimed to have been composed word for word from primeval demigods, Tages and Tarchon. Its claim for Etruscan provenance was enough to persuade many of its value.

This (4th century c.e.) is another classic sophisticated forgery that may have no other purpose than the amusement of its author (although it claimed to be a compilation of works of six scholars). To strengthen its claims for authenticity it even cited the very shelf-number of a non-existent text:

“the ivory book” containing a senatus consultum signed by the emperor Tacitus. It was in bookcase 6 at the Ulpian Library, where the “linen books” containing the deeds of Aurelian were also housed.

Nothing could have done more to enhance the credibility of this dedicated but self-mocking imaginary scholar, whose curiosity embraced even the smallest details of imperial lives and works — who ironically represented himself as admitting to Junius Tiberianus, the prefect of Rome, that “there is no writer, at least in the realm of history, who has not made some false statement. (p.19)

Forgery under the nose of the true author?

Would forgers even have dared to pass off spurious works under the very noses of the authors they were forging? It happened.

Galen is best remembered as a medical writer. He wrote a complaint that he could walk through the streets of Rome and see on sale books claiming to be by himself (Galen Physician) that he had not been responsible for at all. He went on to attempt to explain how readers could tell the difference between his works and the spurious ones circulating under his name.

But this is a point that those familiar with the letters of Paul know, although this comparison is my own, and not Grafton’s that I am inserting here. In a letter that is judged by many scholars to be a forgery itself, “Paul” warns his readers to beware of letters circulating that claim to be from him. So the idea of forgeries within the time and area of their namesakes was certainly a plausible one at the time. See 2 Thessalonians for discussion, and 2:2 in particular.

Galen was also a textual critic who wrote analyses of earlier medical works. In his preface to Hippocrates, On the Nature of Man, he addresses different views of the work, some that had argued the whole book was a forgery and others who had argued but a single line was an interpolation.

Galen argues that the first part of the work was genuine, but the latter part was certainly forged. His arguments:

- the first part was referred to by Plato in Phaedrus, so had to have been in existence then

- the second part contains anachronisms, such as technical terms for “unbroken” and “urines” that early Greek doctors never used but that were only otherwise used by recent medical practitioners.

Julius Africanus, Christian scholar and Roman librarian

Julius Africanus wrote a letter to Origen demolishing any hope of any thoughtful person accepting the story of Susanna as belonging to the original Book of Daniel — which it is attached to in the Greek, though not in the Hebrew version.

Again, his arguments are interesting for their “modernity”:

- The Jews in the disputed text enjoy more freedom than was in fact the case during the Babylonian captivity

- Daniel in the disputed text prophesied in direct speech, unlike the Daniel in the other text who spoke via angelic visions

- The story was too silly to be a Greek mime

- The story contains two crucial elaborate puns — in Greek — so it could not have been a translation from the Hebrew.

Conclusion

Anthony Grafton continues with a discussion of Jerome’s detection of forgeries, even in the supposed canon of Biblical works, and then moves into the Middle Ages, and on to the present day.

It is interesting to see that the tools or arguments used today for detecting forgeries were in use even in ancient times. It is equally interesting to see that the arguments that exposed forgeries then failed to persuade those who wanted to believe they had the genuine literature, just as much as the same tools today fail to convince any Mulder who “wants (or needs) to believe”.

Can recommend an earlier companion post to this one, Rosenmeyer’s Ancient Epistolary Fictions.

Like this:

Like Loading...