If you are more interested in

- why a second messiah in the first place? and

- why the tribe of Joseph for a second messiah?

skip to the end of this post where I cite one of several explanations.

I don’t know the answer to the question in the title (in part because much depends upon how we define and understand the origins of “Christianity”) but I can present here one argument for the possibility that there was a belief among various Judeans prior to the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE that a future messiah was destined to be killed. (This post goes beyond previous posts addressing messianic-like interpretations of the Suffering Servant passage in Isaiah 53 that we find in Daniel and the Enoch literature and builds upon other earlier posts addressing the evidence in later rabbinic and other Jewish writings.)

I don’t know the answer to the question in the title (in part because much depends upon how we define and understand the origins of “Christianity”) but I can present here one argument for the possibility that there was a belief among various Judeans prior to the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE that a future messiah was destined to be killed. (This post goes beyond previous posts addressing messianic-like interpretations of the Suffering Servant passage in Isaiah 53 that we find in Daniel and the Enoch literature and builds upon other earlier posts addressing the evidence in later rabbinic and other Jewish writings.)

We focus here on a 2005 article by David C. Mitchell in Review of Rabbinic Judaism, “Rabbi Dosa and the Rabbis Differ: Messiah Ben Joseph in the Babylonian Talmud“. I find a number of aspects of the article questionable, but nonetheless Mitchell does present a somewhat technical argument in support of the possibility of a pre-Christian belief in a slain messiah.

Recall that in my recent post, Suffering and Dying Messiahs: Typically Jewish Beliefs, we read a Jewish narrative from the early 600s CE describing a Messiah son of Joseph being slain in battle against end-time forces of evil. The earliest surviving reference to the Messiah ben (=son of) Joseph is in the Talmud. If you are like me your first reaction to hearing that will be “How can writings up to several centuries into the Christian era possibly be used as reliable sources for events and ideas in first century Palestine?” But also if you are like me you will be at least open to hearing the case being made. So here it is as I understand it.

Talmud: Rabbinic writings made up primarily of two parts, the Mishnah and the Gemara.

The Mishnah purports to be the written collection of oral traditions of rabbinic debates and teachings. The Mishnah was completed around 200 CE.

The Gemara is rabbinic commentary on the Mishnah and is said to have been composed between 200 CE to 450 CE.

There are two broad chronological eras represented in the Talmud: the Tannaitic and the Amoraic.

The Tannaim is identified by Hebrew text and represents ideas prior and up to 200 CE.

The Amoraim is identified by Aramaic text and represents the period subsequent to 200 CE.

In the Mishnah we sometimes read both Hebrew and Aramaic text in the one section. We understand that the Aramaic text has been added by rabbis post 200 CE to fill out or clarify the earlier Hebrew account.

It will help to know some important terms relating to the Talmud. I explain these (hopefully not misleadingly simplified) in the side box.

The earliest known references to Messiah ben Joseph are found in a section (or tractate) called Sukkah. (Scroll through the Talmud page at http://www.halakhah.com to see where it sits in the broader collection.) The Sukkah tractate relates to the Feast of Tabernacles (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sukkot).

I copy the first of these passages, Sukkoth 52a, as Mitchell himself sets it out, with the later Aramaic passages in italics, but I have added bolding to make it clearer:

“And the land shall mourn family by family apart. The family of the house of David apart and their women apart” (Zech. 12:12). They said: Is not this an a fortiori conclusion? In the age to come, when they are busy mourning and no evil inclination rules them, the Torah says, “the men apart and the women apart.” How much more so now when they are busy rejoicing and the evil inclination rules them. What is the cause of this mourning? Rabbi Dosa and the rabbis differ. One says: “For Messiah ben Joseph who is slain;” and the other says: “For the evil inclination which is slain.” It is well according to him who says, “For Messiah ben Joseph who is slain,” for this is what is written, “And they shall look upon me whom they have pierced, and they shall mourn for him like the mourning for an only son” (Zech. 12:10); but according to him who says, “The evil inclination which is slain:” Is this an occasion for mourning? Is it not an occasion for rejoicing rather than weeping?

I understand from Mitchell’s discussion that the highlighted words above are translations of Aramaic text. The remainder is rendered from Hebrew.

Accordingly we have in this section of Mishnah, typically dated prior to 200 CE, later rabbinic additions in Aramaic. But the Aramaic text is quoting references to Messiah ben Joseph that are in Hebrew text.

Mitchell argues that the Aramaic script is the work of Amoraic (post 200 CE) rabbis commenting on a tradition from the Tannaitic era (prior to 200 CE). He disagrees with another scholar (Joseph Klausner) who believed we should interpret the passage as indicating that the tradition of Messiah ben Joseph itself originated some time in the later Tannaitic era (200-450 CE).

Let’s back up a little. Let’s see what light the broader context might be able to shed on the question of dating.

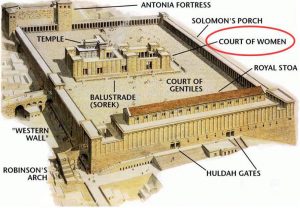

Immediately prior the section mentioning Messiah ben Joseph we read about worshipers at the end of the first day of the Feast going down to the Court of Women at the Temple where a significant change is encountered: Continue reading “How Early Did Some Jews Believe in a Slain Messiah son of Joseph?”