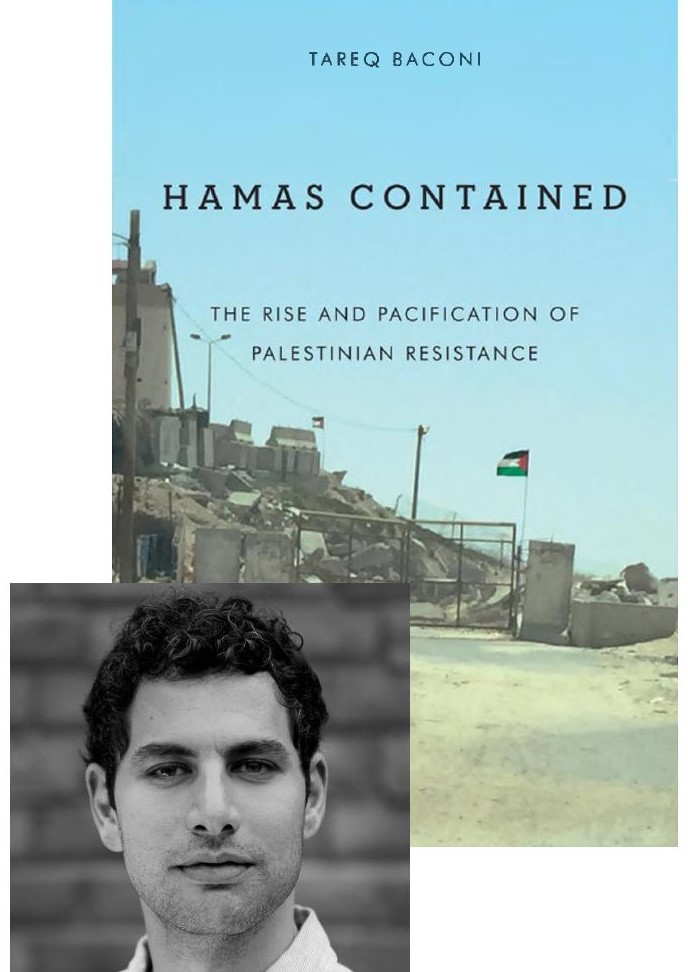

I have read four studies of Hamas and have this evening begun to update my information by beginning my fifth, Hamas Contained : The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance by Tareq Baconi. So far I have only read the Preface and already I wish everyone could read it and follow up by speaking out and doing their little bits to spread light on a world that is too often lost behind distortions of reality.

Sections of the Preface that hit home with me:

The simplistic binaries that frame conversations of Palestinian armed struggle evoke the condescension expressed by colonial overlords toward the resistance of indigenous peoples. “Palestinians have a culture of hate,” commentators blast on American TV screens. “They are a people who celebrate death.” These familiar accusations, quick to roll off tongues, are both highly effective at framing public discourse and insulting as racist epithets.

Bolded emphasis in all quotations is my own.

I have often found discussions about Hamas very difficult so when I read the following I recognized something immediately:

The prevailing inability or unwillingness to talk about Hamas in a nuanced manner is deeply familiar. During the summer of 2014, when global news rooms were covering Israel’s military operation in the Gaza Strip, I watched Palestinian analysts being rudely silenced on the air for failing to condemn Hamas as a terrorist organization outright. This condemnation was demanded as a prerequisite for the right of these analysts to engage in any debate about the events on the ground. There was no other explanation, it seemed, for the loss of life in Gaza and Israel other than pure-and-simple Palestinian hatred and bloodlust, embodied by Hamas.

Totally absent from any discussion, it seems, is any serious consciousness of the “broader historical and political context of the Palestinian struggle”.

Whether condemnation or support, it felt to me, many of the views I faced on Palestinian armed resistance were unburdened by moral angst or ambiguity. There was often a certainty or a conviction about resistance that was too easily forthcoming.

Oh yes. Black and white. Right and wrong. Good and evil. The simplistic paradigms that have always guaranteed the perpetuation of ignorance and suffering.

Tareq Baconi explains that what he attempts to do in the book is to

peel back all the layers that have given rise to the present dynamic of vilifying and isolating Hamas, and with it, of making acceptable the demonization and suffering of millions of Palestinians within the Gaza Strip. . . . This book works to advance our knowledge of Hamas by elucidating the manner in which the movement evolved over the course of its three decades in existence, from 1987 onward. Understanding Hamas is key to ending the denial of Palestinians their rights after nearly a century of struggle for self-determination.

At the end of his Preface Baconi discusses the wide ranging archival and other sources he has used for this purpose.

Story 1

Personal anecdotes have the potential to encapsulate hundreds of words of analysis. One discussion was with a young boy that took place about a year after the 2014 Israeli assault on Gaza:

The conversation was during the Islamic month of Ramadan in 2015, and everyone was sluggish from the June heat. I asked him about the school year he had just finished and whether he was happy to be on holiday. He shrugged. “Sixth grade was fine,” he said, “a bit odd.” He was in Grade A and he used to look forward to playing football against Grade B. That past year, though, the school administration had merged several grades together. The classes were crowded and the football games less enjoyable. I wondered aloud to the boy why the school administration had done that. Annoyed that I was not engaging with the issue at hand, that of football politics, he answered in an exasperated tone. “Half of the Grade A kids had been martyred the summer before,” he snapped. The kids who had survived no longer filled an entire classroom.

Story 2

Another conversation with a Gazan boy (driving his taxi) who was about to graduate from his final school year:

I asked him what he wanted to do postgraduation — always a fraught topic in a place like Gaza. He said he “was thinking of joining the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades,” Hamas’s military wing. I had seen posters throughout the city and on mosque walls announcing that registration was open for their summer training camps. A few of his friends had apparently signed up. Why, I asked. He replied that he wanted to “fight the Jews.” He’d never seen one in real life, he added, but he had seen the F-16s dropping the bombs.

Almost a decade into the blockade of the Gaza Strip, which had begun in earnest in 2007, “Jew,” “Israeli,” and “F-16” had become synonymous. A few years prior, this boy’s father would have been able to travel into Israel, to work as a day laborer or in menial jobs. While it would have been structurally problematic, that man would have nonetheless interacted with Israeli Jews, even Palestinian citizens of Israel, in a nonmilitarized way. This is no longer the case. One could see in my driver how the foundation was laid for history to repeat itself. Resistance had become sacred, a way of living in which he could take a great deal of pride serving his nation.

Reality is complex

Here is why I wish many people would read this book: Continue reading “Understanding Hamas in Gaza”