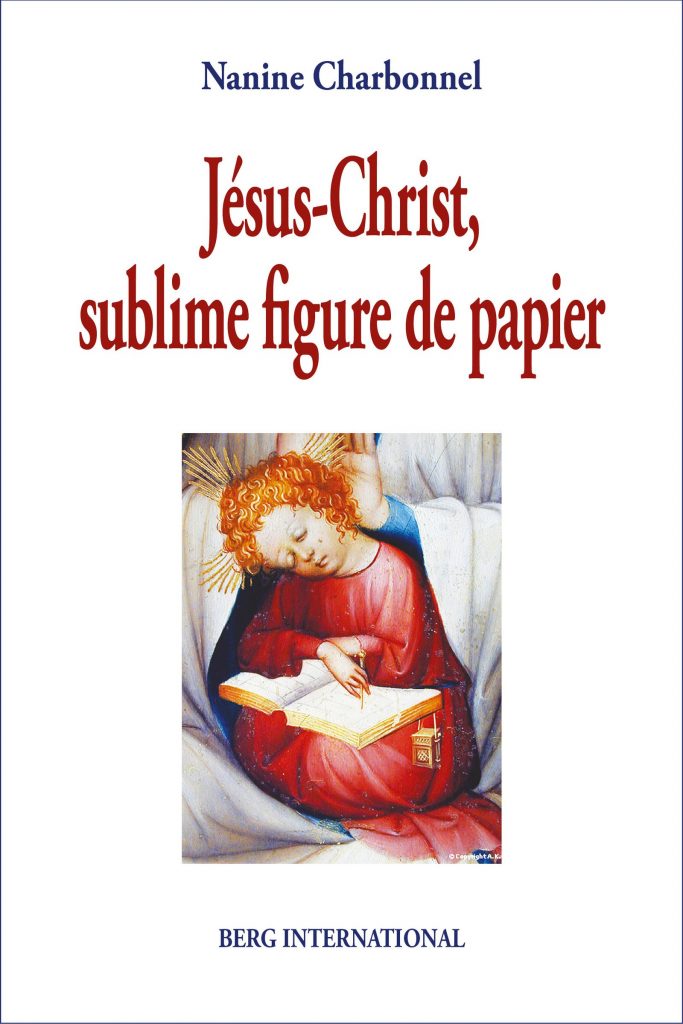

My routine was interrupted this week with the arrival of a new book in the mail, Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier by Nanine Charbonnel. Nanine Charbonnel is an emeritus professor of philosophy who describes herself as a specialist in hermeneutics. The publisher of her new book has given prominence to the fact that it contains a preface by Thomas Römer.

My routine was interrupted this week with the arrival of a new book in the mail, Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier by Nanine Charbonnel. Nanine Charbonnel is an emeritus professor of philosophy who describes herself as a specialist in hermeneutics. The publisher of her new book has given prominence to the fact that it contains a preface by Thomas Römer.

I once posted on another French philosopher who contributed articles and books presenting a case that Jesus originated as a mythical figure, Paul Louis Couchoud, and would like to do the same for Nanine Charbonnel. Unfortunately, my high school and one year of undergraduate French is very rusty indeed and I rely heavily on machine translation as my first foray into what lies before me. Expect me to appeal to readers more fluent in French to help out from time to time.

I think I can post a machine translation (with minor corrections, added fluencies and clarifications from me) of Römer’s preface without infringing copyright. I have changed the formatting (paragraphing, highlighting) totally, though:

This book which will surprise and undoubtedly also disturb many readers could also have been entitled “The Invention of Jesus”. Its author, Nanine Charbonnel, professor of philosophy breaks a taboo that has existed for more than a century in academic research on Jesus of Nazareth, the origins of Christianity and the New Testament.

From the beginning of the so-called “historico-critical” exegesis arises the question of the “historical Jesus”. His virgin birth, his encounter with the devil at the beginning of his activity, his miracles, even his resurrection of the dead, are understood by the Rationalists as mythical reinterpretations of a human figure.

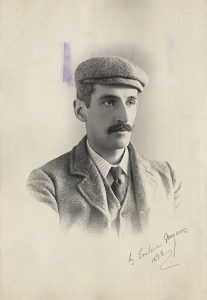

- Thus, Ernest Renan, in his inaugural lecture at the College de France, spoke of “the man Jesus” who “reached the highest religious level that ever before man attained” was “deified” after his death (OEuvres Complètes, n, 329-330). In 1862 these words caused a scandal and provoked the temporary dismissal of Renan from his professorship at the College de France.

- Renan’s statement is part of what is now called “the first quest” of the historical Jesus, which began in the eighteenth century with the posthumous publication of the texts of Hermann Samuel Reimarus by the philosopher Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. Reimarus highlighted the historical Jesus who never wanted to found a new religion, even the Church, but who was an eschatological preacher. His failure was transformed by his disciples who created the myth of his resurrection and ascension. A distinction was made between the “historical Jesus” and the “Christ of faith”, a distinction accepted until today by the totality of university researchers and historians.

At the beginning of the research on the historical Jesus, the question of the proofs of his existence (outside the New Testament texts) was nonetheless posed.

- In the middle of the nineteenth century, Bruno Bauer argued that Christianity born in the second century was a sort of syncretism combining different religious ideas (Jewish, Greek, Roman). Jesus is not at the origin of this Christianity, but a literary fiction to give this “new religion” a founder.

- At the beginning of the twentieth century the German philosopher Arthur Drews published a book The Christ Myth, in which he considered the figure of Jesus as the personification of an earlier Christic myth, showing that all the epithets of Jesus were borrowed from mythologies Jewish and Greek.

These theories remained marginal however and, despite the fact that in the 1st and 2nd centuries there are no texts outside the New Testament clearly attesting to the existence of a Jesus of Nazareth, the historicity of such a character is almost no longer questioned.

- Thus Daniel Marguerat, eminent exegete of the New Testament, says: “the meaning of his deeds and actions, not his existence, is debated today” (p.13, in his Introduction to the edited volume Jesus de Nazareth. Nouvelles approches d’une énigme, Geneva, Labor and Fides, 1998).

According to Nanine Charbonnel, author of this book, this distinction between the historical Jesus and the reinterpretations of his life and death in the Gospels has been detrimental to research. Relying on a “rationalization” of evangelical texts, it has prevented the deep understanding of these texts by questioning them almost exclusively from this idea of a historical core and thus seeking the historical basis of certain pericopes as well as indications of borrowing from Judaism or reinterpretations after the death of Jesus in others. Faced with the affirmation shared by believing scholars and agnostic intellectuals that Jesus is a historical figure of whom we know almost nothing historically, the author of this book proposes to read the New Testament texts from the idea that Jesus Christ would be a “paper figure”. The philosopher’s approach includes a severe critique of hermeneutics, and in particular the current called “hermeneutic phenomenology”.

This book proposes to read the Gospel tales as midrashim, reminding us rightly that it is impossible to read the New Testament texts without locating them in their relation to the Old Testament (in Hebrew and Greek). As a midrash, an exegesis and reinterpretation of earlier texts, evangelical tales set up a theology of fulfillment through narratives, drawing largely on the texts and themes of the Hebrew Bible. Nanine Charbonnel shows it in pedagogical tables indicating the different borrowing and rewriting that can be found behind the tales of the Gospels. She then details the function of the characters appearing in the Gospels, like the twelve apostles, representing the twelve tribes of the new Israel, and Mary, the Jewish people who begets the Messiah. Jesus is the new Adam, the new Moses, the new Elijah and the new Elishah, but also the new Joshua and the incarnation of the “suffering servant”, a messiah who brings together different messianic traits. The Gospels no longer appear as compilations but as creative works repeating and transforming statements in the Hebrew Bible.

To understand the figure of Jesus Christ as a sublime invention of the human mind is the main thesis of this book. It is possible that many readers are reluctant to follow the author in this way. Nevertheless, it is difficult to deny the midrashic character of many pericopes of the Gospels. Everyone will be free to draw conclusions from this midrashic reading which will have the great merit of going beyond the dichotomy between “myth” and “history”.

Before I post an outline of Charbonnel’s discussion in her opening chapter I want to address the word “midrash” and how it has been related to the gospels. I don’t believe this will seriously detract from her presentation, or from the theses presented by others who have used the term in similar ways, but I think we should be aware of scholarly differences pertaining to the term whenever we see it.