Forgive the longer than desirable delay since my last post on Nanine Charbonnel’s book, Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier. (See the Charbonnel tag for all posts in this series.) The fault lies entirely with my failure to maintain my knowledge of basic French over the years so that it’s been a harder than usual struggle to be reasonably confident that I have grasped the details of the rather technical discussion in the second chapter.

Forgive the longer than desirable delay since my last post on Nanine Charbonnel’s book, Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier. (See the Charbonnel tag for all posts in this series.) The fault lies entirely with my failure to maintain my knowledge of basic French over the years so that it’s been a harder than usual struggle to be reasonably confident that I have grasped the details of the rather technical discussion in the second chapter.

The theme of this chapter is the remarkable range of meanings that can be teased out of the basic consonants of the early Hebrew biblical text. It is a mistake, Charbonnel points out, to think of the Hebrew text as being vowel-less. Yes, it is true that vowels were not written down as part of the original text, but without vowel sounds the consonants could not be pronounced at all. Seen from that perspective the vowel sounds can be considered the very soul, life, of the otherwise lifeless consonant text.

Further, the fundamental unit of the Hebrew language, consistent with other Semitic languages, was a (generally) three consonant root. To this three-letter foundation could be added suffixes and prefixes and, and by changing the internal vowel sounds one could produce a very wide array of nouns, adjectives and verbal forms. To paraphrase a quotation Charbonnel draws from a doctoral thesis by David Banon (University of Strasbourg),

it is as if the Semitic language had an unfinished character, a character that requires the reader to complete. In this respect the Hebrew text would look like the Creation that is not yet quite completed and that requires the man, the Adam, to perfect.

With such flexibility inherent in the text there is a possibility of endless play on interpretations and meanings.

Some other ways in which the Hebrew text acquires such plasticity:

Hebrew letters are also numbers. So words have numerical values. The sum of the value of each letter can be compared with the value of another word and inferences of interpretation can be thus drawn between the two words.

Each letter has a meaningful name. The letter for “b” (ב), for instance, is beth (or rather, BTH), and beth means house. So each consonant can be likened to a meaning or another word.

Some letters double as grammatical essentials. He (ה) is also the definite article, “the”; it is also a feminine ending; and also a word-ending signifying direction (towards); it can also indicate a question.

Certain letters can change the meaning or time or tense (whether an action has been completed or is on-going) associated with a word. To roughly paraphrase rather than exactly translate another passage,

When there is no yod (י) the verb’s meaning is assigned to the past, the action is accomplished. When there is a yod prefix, the verb is unfulfilled, or conditional, subjunctive. To assign the sense of future, simply add a yod before the verb. The yod is shaped like a hand with a pointing finger, indicating something to be arrived at or decided. So the future is open. And it is because of this openness that yod is the first letter of the name of the Lord, Yahweh. Whenever a yod will be written or read its will evoke the name of the Lord and His opening up of the future.

Encore plus étonnant, il suffit bien d’une autre lettre, un waw (jouant le rôle de préposition, donc avec une voyelle), pour ‘’convertir” (sémantiquement) la forme verbale de l’inaccompli en accompli (en gardant cette fois, pour le ‘’il”, le yod, qui marquait le futur), et inversement (la forme de l’accompli, avec son suffixe). C’est le fameux ‘’waw conversif” :

« Ce W- qui ajoute une nuance de succession est parfois appelé waw conversif, car il donne à chacune des formes la valeur temporelle ou aspectuelle qui est celle de l’autre forme quand cette dernière n’est pas précédée de waw. Les formes précédées de ce waw sont appelées formes converties. Ce trait syntaxique et stylistique, […] est caractéristique de la langue littéraire biblique. »

Le phénomène est énigmatique.

Peut-être son apparition est-elle liée à la narration, et elle s’expliquerait dans le cadre de l’évolution de celle-ci (il correspond à un passé simple, dans une suite narrative). Quoi qu’il en soit de son origine, il paraît cependant difficile de nier son existence sémantique, et la structure mentale qu’il peut forger. Qu’en est-il de l’influence de ce mécanisme sur la pensée biblique ? Faut-il dire que l’accompli obtenu ainsi, peut exprimer «le temps passé mais avec l’espoir de l’avenir» ? Il nous semble au moins qu’il accentue encore l’instabilité dans la temporalité, que nous allons approfondir plus loin.

Restons-en au poids des lettres. Insistons sur un degré de plus dans la possibilité de confusion. Pour cette transformation de la forme inaccomplie en un accompli, le waw dit conversif (ou inversif) se distingue du waw conjonctif (car le waw peut aussi être simplement la conjonction de coordination : le ‘’et” français), en ce qu’il est vocalisé ‘’a” et est suivi d’un redoublement de la consonne suivante. Mais quand il s’agit de transformer la forme accomplie (en inaccompli), le waw qui la précède est vocalisé ‘’shewa” (= é), ce qui ne permet pas, dans ce cas, de le distinguer d’un waw conjonctif…

Ainsi c’est le contexte seul, mais aussi parfois la pure décision du lecteur qui interprète le waw comme étant la conjonction ‘’et”, ou comme étant le signal de la forme inversée (qui par un accompli signifie alors un inaccompli…).

Charbonnel, 44-46

Charbonnel follows with a discussion about what I take to be the waw consecutive and that looks interesting but, alas, that I have given up attempting to translate even with the aid of Google. I quote the passage in the side-box for anyone with the competence to do the honours and be kind enough to produce a translation in the comments.

The final point enabling further multiplications of interpretations listed, surely especially significant at the time the New Testament works were being composed, was familiarity of many authors with Aramaic as well as Hebrew. The languages are very close but significantly some differences involve reversals of meaning.

Such details about the scripts and languages need to be kept in mind whenever we seek to make sense of the biblical writings, Charbonnel concludes.

Mystical Power of the Letters

— It is the written text that is sacred but what is read or seen on the page can be different from what is actually read aloud or spoken. The writing is sacred but the meaning is impossible to comprehend without an instructor.

— While the text itself is sacred, there can be some confusion in the meaning. Puns and word-play, moreover, can become an integral part of the meaning of the text and not mere incidental coincidences. Some letters are very similar and easily confused (e.g. resh ר and daleth ד) with potentially disastrous changes in meaning. Again to offer another crude paraphrase of my interpretation of a passage in Charbonnel’s text:

Letters serve not only as support for revelation but as an integral part of it. Since the world stands on the Torah, according to one tradition, any attack or breaking of the text puts creation in danger. . . . An 11th century saying: “If by accident you omit or add a single letter you destroy the whole world.”

It is forbidden to allow two letters to touch one another in order to preserve the distinctive sacredness of each, with all of its variable potentials of meaning. Quoting Marc-Alain Ouaknin, Mystères de la Bible,

The letters are all autonomous. Every letter is a world, every letter is a universe. The scribe therefore scrupulously writes each letter paying attention that there is no contact between two letters. In case that happens the book would be unfit for liturgical reading. (Machine translation, p. 48)

Letters, their forms, ranks, numbers, meanings, have something of a mystical power:

In Hebrew, father and mother begin with Aleph, son and daughter begin with Beth: Beth is thus the second generation, the one who has already received the teaching of her eldest, Aleph. (Charbonnel’s quotation, p.49, from LES SYMBOLES DANS LA BIBLE: LE SENS CACHÉ DES LETTRES HÉBRAÏQUES )

In the back of my mind as I read these pages I am wondering to what extent it all applies to the authors of Second Temple and early Christian texts. As if reading my mind Charbonnel states:

The belief that the letters of the alphabet are sacred powers is not only found in the esoteric doctrines of the Middle Ages (the Kabbalah) but certainly also in the period of the writing of the Old Testament texts (from the sixth to the first century before Christ.) (machine assisted translation, p. 49)

How the Bible Stories are Shaped by the Above Mechanisms

Continue reading “Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier. Chap 2a. The Sacred and Creative Power of the Hebrew Text”

Like this:

Like Loading...

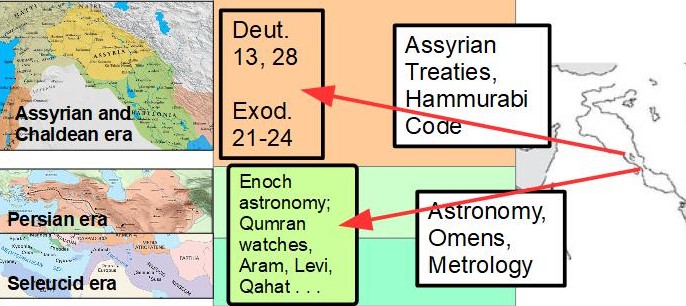

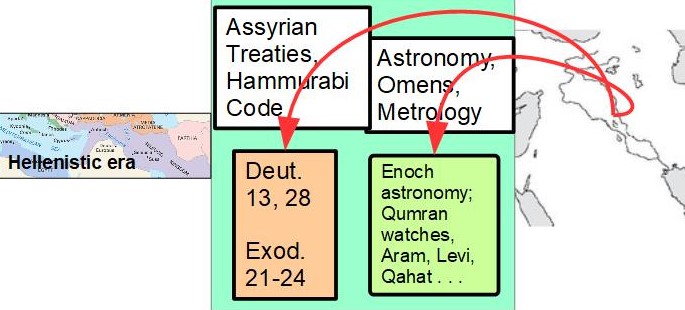

I have been posting on points of interest in Seth Sanders’ From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon and have reached a point where I cannot help but bring in certain contrary and additional perspectives from another work I posted on earlier, Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.

I have been posting on points of interest in Seth Sanders’ From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon and have reached a point where I cannot help but bring in certain contrary and additional perspectives from another work I posted on earlier, Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.