Definitions, a necessary complement to the previous post and clarification for future posts. . . .

Definitions, a necessary complement to the previous post and clarification for future posts. . . .

Raphael Lataster asserts that he is “not a mythicist per se”, with the term “mythicist” meaning, in this context, “the view that Jesus did not exist.” He explains,

I do not assert that Jesus did not exist. I am a Historical Jesus agnostic. That is, I am unconvinced by the case for the Historical Jesus, and find several reasons to be doubtful. (pp. 2 f)

Lataster compares the term “mythicist” with “strong atheist” and “hard naturalist” and the term “historicist” with “theist”. The “historical Jesus agnostic” is compared with the “God agnostic”.

I understand the comparisons but feel they do not sit comfortably with those mythicists who have continued to hold fast to their Christianity.

Lastaster proposes a third term, “ahistoricist“,

to encompass both the ardent ‘mythicists’ and the less certain ‘agnostics’. This avoids the false dichotomy, which I think historicists (much like theists) have been taking advantage of. They often frame the debate as only being between the right and the wrong, the reasonable and righteous historicists versus the silly mythicists, ironically appearing as unnuanced and dogmatic fundamentalists in the process. With my proposed terminology, it shall become much more transparent that there are many more scholars that question Jesus’ historicity than is typically thought; that this is not such a silly idea. (p. 3)

I can say that I find the evidence for a historical Jesus to be inadequate and conclude that there is no need to postulate a historical Jesus to explain the letters and gospels and origins of Christianity. In that sense I could call myself a mythicist, but my position would be tentative. I would remain open to new evidence and insights emerging to change my mind. That sounds the simplest and most “scholarly” approach to me, but I have to admit that terms have long been charged with prejudicial associations and for many people the term “mythicist” implies an unnecessary dogmatism. Or would Lataster’s definition make me an “agnostic” — one who does not believe in the historicity of Jesus until further evidence or insights are presented? So I can understand Lataster’s point. Except that scholars like Thomas Brodie — who are Christians who believe Jesus was not a literal historical person — would surely prefer a comparison that did not carry associations with atheism. I suspect liberal Christians who are atheists yet believe in a historical Jesus likewise would not fit comfortably into the comparison. The world is a complex place and the making of definitions is often hard.

Raphael Lataster introduces yet another term, the Celestial Jesus. This is the Jesus of Paul, Lataster explains (p. 13). It appears to me that Lataster is following Richard Carrier at this point. Carrier’s definition of a “minimal Jesus myth” consists of the following five points:

-

At the origin of Christianity, Jesus Christ was thought to be a celestial deity much like any other.

-

Like many other celestial deities, this Jesus ‘communicated’ with his subjects only through dreams, visions and other forms of divine inspiration (such as prophecy, past and present).

-

Like some other celestial deities, this Jesus was originally believed to have endured an ordeal of incarnation, death, burial and resurrection in a supernatural realm.

-

As for many other celestial deities, an allegorical story of this same Jesus was then composed and told within the sacred community, which placed him on earth, in history, as a divine man, with an earthly family, companions, and enemies, complete with deeds and sayings, and an earthly depiction of his ordeals.

-

Subsequent communities of worshipers believed (or at least taught) that this invented sacred story was real (and either not allegorical or only ‘additionally’ allegorical).

(Carrier, p. 53)

Lataster writes

[W]e can refer to the Biblical Jesus, or more specifically, the Gospel Jesus, as the general version of Jesus portrayed in the Gospels and held dear by believers, while the Celestial Jesus refers to the possible early Christian view of a Jesus that did not appear on Earth, as portrayed in the Pauline Epistles. (p. 13)

I fear the terms “mythicists” or “ahistoricists” may run into difficulties up ahead with such a foundation. Though Earl Doherty (whom Carrier follows), and before him, independently, Paul-Louis Couchoud, postulated a Pauline Jesus who was entirely “celestial”, Paul’s letters can be read differently. As Roger Parvus has shown, it is possible that Paul’s letters allow room for a Jesus who came to earth for a short time in order to be crucified.

Another “mythicist” option is also plausible: it is not inconceivable that Paul’s “crucified Christ” was preached in opposition to another Christ, a conquering Christ, as per the Book of Revelation, a Christ who was at no point crucified — according to Couchoud’s thesis (see “The Creation of Christ: An Outline of the Beginnings of Christianity” by P. L. Couchoud at vridar.info).

Carrier is following Earl Doherty’s thesis at this point, yet despite Doherty’s monumental contribution to raising public awareness of the question of Jesus’ historicity, I do not think that a “celestial Jesus” is a satisfactory notion of an equivalent to a “mythicist” Jesus. To express the point in its crudest terms, myths do not have to be restricted to “celestial realms”. And in the case of the “Jesus myth” idea we do have other options. Other “Jesus myth theories” have postulated a narrative arising in B.C.E. times, in particular around the time of Alexander Jannaus who is on record as having crucified 800 (mostly) Pharisees.

For the sake of compatability and consistency with Raphael Lataster’s discussion, I will try to keep in mind the need to refer to “mythicism” as the more inclusive “ahistoricism“.

The Gospel Jesus

The Gospel Jesus is evidently a figure crafted from a wide range of literary sources. The question for the study of Christian origins is Who/What gave rise to those gospel narratives? Somewhere along the line the Pauline notions gained dominance, although through the second century certain powers found opportunity to forge new concepts in his name. But before that time there were others with quite different notions of “Jesus” — one who had been slain in heaven, another who had been crucified by Herod (not Pilate), and one who had in the meantime descended into a place below the earth in order to release lost souls.

Any definition of a Jesus who is an alternative to a “historical figure” ideally should allow for all such apparent notions of “Jesus”, and more.

We will move on and next look at Raphael Lataster’s analysis of Bart Ehrman’s argument against the “ahistoricist” view and for the “historicist” Jesus.

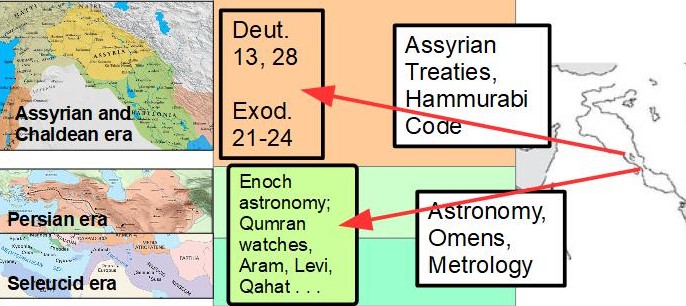

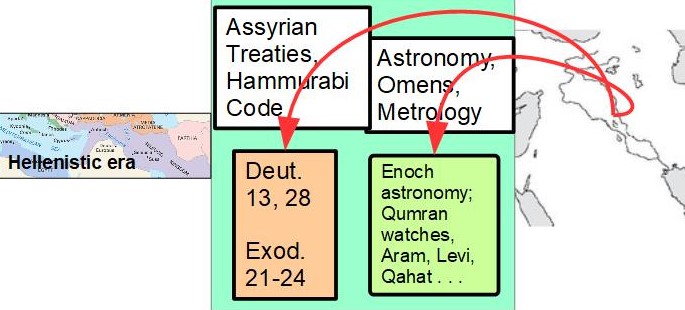

I have been posting on points of interest in Seth Sanders’ From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon and have reached a point where I cannot help but bring in certain contrary and additional perspectives from another work I posted on earlier, Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.

I have been posting on points of interest in Seth Sanders’ From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon and have reached a point where I cannot help but bring in certain contrary and additional perspectives from another work I posted on earlier, Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.