An argument has appeared on the earlywritings forum proposing that an early form of the Book of Deuteronomy was produced in the Persian period — more specifically, in Persian period Samaria.

It is mid-semester break for me and the scholarship relating to Persian period writings in Yehud and Samaria is still fresh in my mind (see the previous two posts) so here’s my chance to offer a critical review of a few details.

Archaeologist Yitzhak Magen’s dogmatic declaration that archaeological excavations “prove unequivocally that the temple on [Mt Gerizim] was built in the middle of the fifth century BCE” (before Nehemiah’s presumed arrival in Jerusalem) is quoted uncritically. Ironically later in the discussion Peter Kirby quotes Gary Knoppers who clearly responds to Magen’s published evidence with a measure of equivocation — Knoppers is not the only scholar to observe that the actual evidence presented is by no means definitive and could point to a shrine or altar rather than a temple. Magen’s quote is presented without any apparent awareness of the entirely circumstantial nature of Magen’s evidence and the doubts raised about his interpretations in the scholarship. (As for me, I simply don’t know if there was a temple on Mt Gerizim in the Persian period but as I will explain below, if there was, in the context of other evidence it would actually pose a problem for the argument that Deuteronomy was a product of the priests of such a temple. )

Magen’s dogmatic quote is followed by Diana Edelman’s conclusion that “it is more logical to assume” a Temple was constructed at Jerusalem in the Persian period in the time of Nehemiah — after Magen’s claim that the Samarian temple was erected before then.

The significance of this chronology for Peter K is that since the Mt Gerizim temple was constructed before the Jerusalem temple, then there was hope — as we find expressed in Deuteronomy — that this would be the sole and only temple for “Israel”. (PK does appear to assume the name “Israel” designated the region of Samaria at this time.)

[Unfortunately Peter concludes this section of his argument by misapplying a quote from C. Behan McCullagh’s Justifying Historical Descriptions. PK’s argument thus far is, he notes, one that “seems like the best explanation” and “in accordance with the way historians use such arguments, no more is implied than that ‘it is likely to be true'” — but adds that there remains “some reasonable doubt about this explanation” and a better explanation might come to his awareness some time. — McCullagh wrote that arguments to the best explanation are far from conclusive (p. 26) and his point about the kind of argument that is “most likely to be true” he applied only to those arguments that meet all 7 conditions that are required for us to justify belief — such as “the battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18th June 1815, and there can be no doubt who won the battle.” But it was encouraging to at least see an effort to apply a historian’s discussions of historical method here.]

Another encouraging point was to see a reference being made to archaeologist Israel Finkelstein’s “Black Hole” paper in which he emphasizes the lack of evidence in Yehud (Persian period Judah/Judea) for the kind of scribal culture necessary to produce any of the biblical writings. This detail coheres with Peter Kirby’s case for Deuteronomy being in an early form as a pro-Samarian text, one that justified the Samarian temple on Mount Gerizim — not a pro-Jerusalem document. The Finkelstein point is followed by a copy and paste of a full 12+ pages of Gary Knopper’s chapter in Judah and the Judeans in the Persian Period that notes:

- the demographic strength of Samaria (compared to the low demographic situation of Yehud) in the Persan period — and the “flourishing” of the Samarian economy up until the early Hellenistic period.

- Hebrew script was used alongside Aramaic — though the supporting citations Knoppers applies here greatly qualify that statement.

- Most names of the period were Yahwistic.

- Cultural exchanges existed among Jews of Elephantine, Yehud and leaders of Samaria.

- Recent excavations “suggest” that “some sort of sanctuary or temple existed on Mt. Gerizim”.

This is followed by other indicators of the pro-Samarian interest of Deuteronomy, including a reference to a 2011 article by Stefan Schorch (compare my own discussion of a Schorch paper) — and arguments based on archaic Hebrew. No reference is made to controversies related to the linguistic arguments — see reference #12 in an earlier post.)

Finally, reference is made to the Yahwist temple at the Persian period Judean colony in Egypt at Elephantine. For PK, this colony followed “pro-Judean tradition” rather than Samarian according to correspondence discovered at the site. He appears to be unaware of Gard Granerød’s Dimensions of Yahwism in the Persian Period where we read:

Finally, the [Elephantine] community’s orientation towards Jerusalem and Judah suggests that the community considered itself affiliated with Jerusalem and Judah, perhaps as a diaspora community. At least two official letters written to Judah and Jerusalem are known. . . . The letters to Jerusalem and Judah were written against the background of the conflict with the Egyptian priests of Khnum and the local Persian administration in Upper Egypt. Assumedly, the conflict about the temple of YHW sharpened the community’s identity as Judaeans by providing an impetus to reconfirm its ties with the homeland, Judah. However, regardless of whether this was the case or not, the Elephantine Judaeans did not only orientate themselves towards Judah and Jerusalem; they also maintained contact with the Sanballat dynasty in Samaria (A4.7:29 par.). The Elephantine Judaeans received assistance from Samaria by means of a statement. The statement was given by a representative of the Sanballat dynasty in Samaria together with the governor of Judah (A4.9). Regardless of what implications this cooperation between Samaria and Judah may have for the political history of the provinces of Judah and Samaria, the point here is that the Elephantine Judaeans, by also orienting themselves towards Samaria thus displayed a special relationship with Samaria, a relationship that in turn seems to have been confirmed by the ruling dynasty in Samaria. (p. 32)

Here PK overlooks what might be the most damning detail against the plausibility of Deuteronomy being a product of Persian period Samaria. That fact that most personal names found were Yahwistic, the evidence for at least a shrine of Yahweh in Mt Gerizim and assuming a Temple to Yahweh somewhere in Samaria at the very least, — all of that data needs to be studied in the context of contemporary Yahwistic practices, not interpreted through the text of Deuteronomy itself. It is the date of Deuteronomy that is in question here — not the date of Yahweh worship.

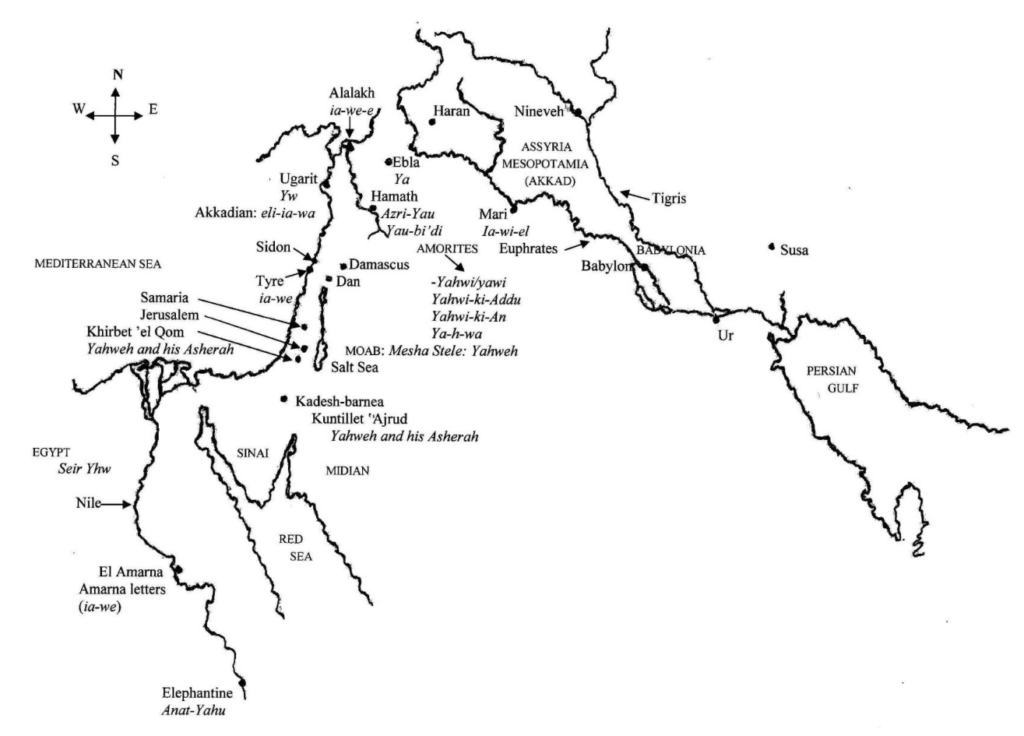

The cult of Yahweh or of some form of that name is found throughout the Levant. It is not unique to Samaria or Judea.

The Elephantine finds demonstrate that the cult of Yahweh followed practices that were alien to the precepts we find in Deuteronomy. The simple fact of the existence of a temple to Yahweh in Elephantine undercuts the notion that priests of Yahweh (see the above quote for cordial relations between Samaria and Elephantine) demanded a single place of worship for Yahweh. Further, Yahweh was worshipped alongside other deities, including his wife. See the linked references in the previous post. It is not until the Hellenistic period that archaeology locates specifically “biblical” precepts being embraced by communities in Palestine.

As for Russell Gmirkin’s thesis of a Hellenistic date and Alexandrian provenance for the Pentateuch, including Deuteronomy, it remains untouched by the above criticisms and coheres more neatly (according to McCullagh’s principles of sound historical argument) with both the archaeological and textual witnesses.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I had the understanding that after “the Return” the Judah sort ordered the Elephantine cester to destroy its temple and the Samaritans to do the same with their temple. I also was lead to believe that a small army was sent to Samaria to carry out the destruction of their temple as the only temple was to be in Jerusalem. This seems to make sense as the temple in Jerusalem was a major profit center for the priesthood and they didn’t want any competition. There was no ideological rationale for the one temple policy that I can glean from my reading.

You’re thinking of Hasmonean events in the second century — that’s when the Judeans compelled others to follow their rules. Like some modern day politico-religious extremists.

I had assumed a Persian-era origin hypothesis was linked to the story of Josiah’s reforms.

It seems a Samaritan provenance would not be very consistent with Deuteronomy being ‘discovered/planted’ by Josiah’s chief propagandist.

It may have been circular reasoning, but it was the central pillar was it not?

If Josiah’s legacy has now been thrown under a bus, what problem does this Samaritan hypothesis even offer to solve?

Oops, I am confusing myself. Josiah would be pre-Persian of course!

I don’t recall the account of the reforms being linked to scribes of the Persian era, but it sounds as if it might have been the kind of notion that Philip Davies once might have proposed. He was in one sense a “kick-starter” of “minimalism” and at the time he preferred to date things to the Persian period.

From what I understand there is no necessary connection between the two.

The Persian era as a setting for “good times” for the “revival” of the Pentateuchal religion has been well explained as a reaction against certain “sufferings” under the Hellenistic rulers — a common literary motif was to imagine a preceding time when there had been something closer to a “golden age” — and the age preceding the Hellenistic rulers was the Persian one. —

By the way, the author of that discussion once told me that I should never fault an argument for being circular (I was reminded of this by your reference to circularity) — I was admonished to always find a more respectable way to address the argument. Seriously! 🙂

Peter Kirby has already responded to this post on the earlywritings forum. The main critical response, I gather, is this section:

When we’re talking about the request to rebuild Elephantine, we’re talking about ca. 407 BCE. I suggested in this thread that, if there were any pressure from Samaria to prevent a building/rebuilding in Jerusalem, it was already unsuccessful. It thus would seem that the governor of Samaria did not have control over Yehud in the late fifth century BCE, let alone Elephantine. My suggestion was not that Deuteronomy was established as the law of Samaria and from that point forward was used to prevent building sacrificial sites anywhere (and outside of Samaria). But I was trying to find a plausible date and context in which someone could be hopeful that such a program could be achieved, and that date and context that I suggested was 5th century BCE Samaria, as the sacred precinct was being constructed there, the site mentioned in Deuteronomy. The idea of maintaining a central shrine at Shechem may have seemed to have been a hopeful notion even when it was presented in Deuteronomy. It would have soon proved unworkable, as the existing temple at Elephantine (until its destruction in 410 BCE according to the Elephantine text) and a likely site at Jerusalem by the late fifth century BCE would have proven.

So far the northern Israelite origin of Deuteronomy still seems to have plenty to say for it, as documented in this thread. I look forward to the demonstration that we actually can conclude in favor of an Alexandrian provenance for the Pentateuch according to McCullagh’s principles of sound historical argument. It’s always nice to see a good case come to fruition. I appreciate the way that this champions the cause of a neglected argument, just as this thread also takes up a couple arguments (fifth century BCE dating, northern Israelite origin) that has also been relatively neglected, compared to its merits.

I don’t at the moment recall any evidence that Samaria had actual control over Yehud in the Persian era. The evidence addressed, as far as I am aware, on the whole points to collaboration and cultural sharing. Schorch makes that point himself as I have shown in another post here — even though he sets the collaborative authorship of the Pentateuch in the Persian period himself.

The view of the “northern Israelite origin” of Deuteronomy is confused with a Persian-period hypothesis. (Incidentally, I don’t think there are any secure grounds for referring to Samaria as “Israel” during or prior to the Persian period.) They should not be equated. A Samarian or “northern” influence can apply to any time period — Iron Age, Persian or Hellenistic.

The approach of the argument here is “How can we find an argument to undergird the Persian period hypothesis for Deuteronomy?” That’s fair enough but only if we also expend as much effort in studying and comparing alternative hypotheses. That was very much a principle at the heart of McCaugh’s discussion on historical reasoning. Otherwise it becomes little more than confirmation bias in action.

And why the interest in establishing the Persian period hypothesis? I suggest that the rationale is because that’s what the Bible itself implies. It is a return to/persistence in the bad old days of Albrightian “biblical archaeology”, only a little more subtly expressed.

That’s not a valid method — as Israel Finkelstein himself finds himself having to emphasize. (Though he himself falls into the same trap when he relegates the bulk of the biblical corpus to the time of Josiah partly on the basis of implications read into the biblical narrative.) The valid method is to examine all Persian period primary evidence and see what that can tell us. Only after doing that (for each possibe period, too) and in the light of that primary evidence do we seek to understand textual sources that are of an uncertain date but could theoretically be as late as the Hellenistic period.

Scholars who took this genuinely “scientific” method seriously were/are accused of seeking to “debunk”, be “contrarian”, even “antisemitic”, etc. That’s not so at all. There’s no interest in “being different/debunking” etc at all that I have detected. That’s a cheap ad hominem response to avoid facing the methodological problems raised by alternative approaches and conclusions. Sound historical methods too often seem to arouse such hostility among too many with an interest in both Old and New Testaments, sadly. But fortunately there are some inspiring exceptions!