In Revelation 12 the character of the narrator-visionary, John, is exposed to two visions in heaven: one of a woman clothed with the sun, moon and the twelve constellations who is about to give birth to a child; the other of a dragon, a war in heaven (against the one clothed in the heavenly bodies of the sun, moon and constellations?) and the fall of that dragon to earth.

Once the dragon has fallen to earth, we learn that the heavenly events were harbingers of events on earth: the woman in heaven is now seen on earth. The moment she gives birth the child is snatched away from the threatening dragon and taken to heaven. (Recall the book of Daniel: there we read that everything that happens on earth is anticipated in heaven; all earthly battles are first fought out in the skies by the heavenly representatives of the earthly powers.) The dragon then chases after the woman who has to flee into the wilderness for safety. The dragon accordingly changes its plans and turns back to attack the other children of the woman. These are said to keep the commandments of God and hold the testimony of Jesus.

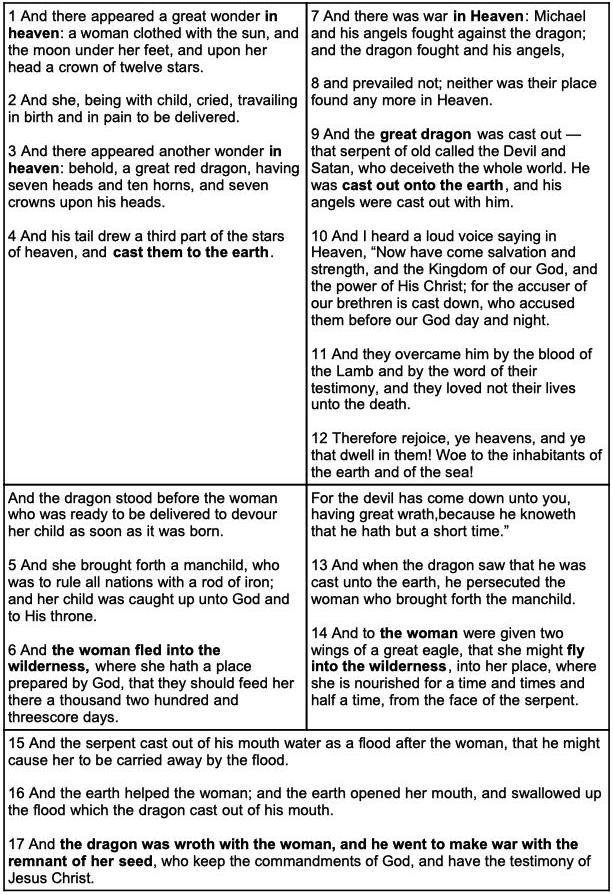

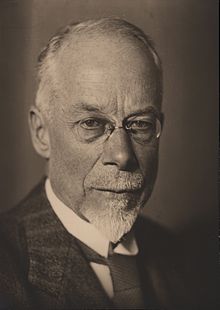

Julius Wellhausen demonstrated the parallel visions in Revelation 12 with the following table:

The following argument is a paraphrase of Wellhausen’s Zur apokalyptischen Literatur.

On earth, the dragon is evidently the Roman empire. (This conclusion derives from a comparison with the information about the beast with seven heads and ten horns in chapters 13 and 17.) The woman appears to be Zion, the twelve-tribes of Israel, who gives birth to the messiah, the one whom Revelation declares will rule the nations with a “rod of iron”. But what kind of Messiah is this? Wellhausen writes,

But it is disputed whether Sion and the Messiah are Christian or Jewish terms here. The question is not already answered by the fact that the Revelation of John as a whole, in its present form, is a Christian book. For the last author used sources and possibly Jewish sources. (Wellhausen, 218 – translation)

The episode of the birth and immediate rapture of the child from earth is unlike any Jewish expectation of a messiah that we know of, but it is also clearly not a part of all we know of Christian views of the messiah, either.

Revelation 12 can hardly be interpreted in any way that allows for a growth of the child to manhood, his life and ministry on earth, nor of his death on earth. Revelation 12 clearly leads readers to understand that the child is snatched up to heaven the moment it is born. Note that in verse 4 the dragon is standing beside the woman waiting for the moment the child is born. There is no scope for the child to grow to adulthood on earth.

Many Christians have interpreted the woman of Revelation 12 as the church. But that view likewise brings insuperable difficulties with it. How can the messiah be the son of the church, one born through the church? The Christian church holds the Christ to be its head, not its child.

If we think of the woman as Israel, however, there is no problem with the idea of the messiah being born from that nation represented as a woman. Jesus was born of his mother Israel or more specifically, Judah.

Another difficulty with reading Revelation 12 as an orthodox Christian text is that it claims the primary enemy of the messiah is the Roman empire. Not the Jews, or any group among the Jews such as the Pharisees or Herodians. In Revelation 12 the only enemy of the messiah is Rome. The Jews are the (loving) mother of the messiah. But Rome is not depicted as the enemy of the messiah from the moment of his birth but even before his birth! How do we make sense of this from a Christian perspective?

Revelation 12 allows no room for a crucifixion of the messiah, certainly not on earth. The Jews are not enemies of the messiah in Revelation 12. Only the Romans are his enemy.

From all of this it follows that the flight of the woman into the wilderness cannot be an allusion to the flight of Christians from Jerusalem to Pella to escape the final destruction of Rome in 70 CE, nor can that flight of the woman in Revelation 12 be a reference to any part of the body of Christianity at any time. The flight to Pella of the Jewish Christians is said to have happened some near 70 years after the birth of the messiah. That time gap is not possible for Revelation 12’s account of the birth of the child and flight of the woman. The two are effectively simultaneous events.

Wellhausen concludes,

The child is not the historical Messiah of the Christians, but an imagined one of the Jews. The vision consists of a Jewish prophecy. (220 – translation)

The author of Revelation 12 is drawing upon the time schedule of the book of Daniel to come to 1260 days. In Daniel we read of a persecution by Antiochus Epiphanes and the visionary of Revelation is expecting a similar time-table with the Roman oppressors.

The woman of Revelation 12 is the portion of the Jewish nation that escaped from the Roman army and continued to maintain their polity elsewhere. These were the Jews who fled from Jerusalem and thus escaped a deadly encounter with Roman forces. These Jews — many Pharisees and scribes opposed by the zealots — became the seed of a future Jewish cultural-religious (rabbinical) revival.

The Romans lost interest in pursuing those Jews and turned against those who remained in Jerusalem.

We know from the later chapters of Revelation that the messiah will come from heaven to crush the forces of evil and rule over all nations.

So why has the author of this chapter described the earthly birth of Jesus at all? What was the point?

Wellhausen finds the answer to that question given by Eberhard Vischer :

Vischer already answered this aptly. There seems to be a compromise between two equal demands. On the one hand, according to the old conception, the Messiah must come forth from the people of Israel, on the other hand, according to Daniel, from heaven. This is rhymed by the assumption that he was born of the mother Sion shortly before the beginning of the three and a half years, but that he was caught up into heaven immediately after his birth and thus did not stay on earth during the time of need. (Wellhausen, 221 – translation)

An analogy can be found in Isaiah chapters 7 to 9: Immanuel (“God with us”) is born at the beginning of a critical time, then disappears from view for a while, and suddenly appears in full glory at the end. That’s Wellhausen’s comment, but he adds that obviously in Isaiah there is no contrast between heaven and earth as abodes for the Christ but that Isaiah does present the pattern of birth, disappearance and return at maturity at the moment of the final stage of the crisis.

So what does all of this have to do with the new series I have begun about Revelation 11 and the command to measure the temple? Continue reading “Revelation 12: The Woman, the Child, the Dragon – Wellhausen’s view”