Was a crucifixion in heaven possible? conceivable?

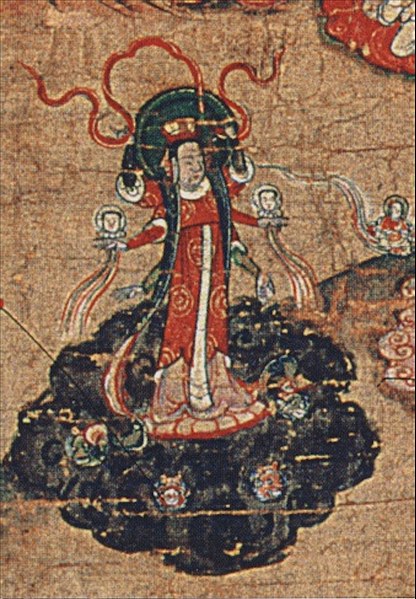

But the following, again, is the cause of men’s dying: A certain virgin, fair in person, and beautiful in attire, and of most persuasive address, aims at making spoil of the princes [= archons] that have been borne up and crucified on the firmament by the living Spirit . . . .

Acta Archelai 8, describing a third century Manichean answer to the question, Why death?

What gave rise to Gnosticism from within Judaism?

Birger Pearson’s answer is very similar to what I think led to the emergence of Christianity from within Judaism. If gnostics fell away from Judaism by rejecting its god as a blind and ignorant Demiurge who gave a law that enslaved its followers to the ways of the flesh, Christianity offered a positive response to similar circumstances, a new covenant grounded in an allegorical revision of the old rather than an outright rejection of it:

Birger Pearson’s answer is very similar to what I think led to the emergence of Christianity from within Judaism. If gnostics fell away from Judaism by rejecting its god as a blind and ignorant Demiurge who gave a law that enslaved its followers to the ways of the flesh, Christianity offered a positive response to similar circumstances, a new covenant grounded in an allegorical revision of the old rather than an outright rejection of it:

One can hear in this text echoes of existential despair arising in circles of the people of the Covenant faced with a crisis of history, with the apparent failure of the God of history: “What kind of a God is this?”‘ (48,1); “These things he has said (and done, failed to do) to those who believe in him and serve him!” (48,13ff.). Such expressions of existential anguish are not without parallels in our own generation of history “after Auschwitz.”

Historical existence in an age of historical crisis, for a people whose God after all had been the Lord of history and of the created order, can, and apparently did, bring about a new and revolutionary look at the old traditions and ‘assumptions, a “new hermeneutic”. This new hermeneutic arising in an age of historical crisis and religiocultural syncretism is the primary element in the origin of Gnosticism.

Pearson, Birger. Gnosticism, Judaism, and Egyptian Christianity. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 1990. p. 51