Here is the final post discussing the introductory chapter of Rivka Nir’s The First Christian Believer: In Search of John the Baptist where she sets out her case for the John the Baptist passage in the writings of Josephus being a forgery.

For readers with so little time, the TL;DR version:

- The baptism of John that is described in Josephus’s Antiquities is shown to be significantly different from Jewish Pharisaic baptism (Pharisee baptism was for ritual cleansing of the body independently from any call for moral purity; the Josephan John’s baptism was for bodily purity but required moral purity as a precondition);

- It is also significantly different from the baptism attributed to the Essenes (and the hermit Bannus) by Josephus — for the same type of reason it was different from the Pharisee baptism);

- That baptism of John appears instead to be very like baptism we read about among Jewish sectarians as in the Qumran scrolls and the Fourth Sibylline Oracle (moral purity was a precondition for the bodily sanctification effected by baptism);

- That same type of baptism we read about in the Dead Sea scrolls and Fourth Sibylline continues to appear among early Jewish Christian sects as witnessed in the Pseudo-Clementines (moral purity a precondition for bodily purification) — the early Christian baptism appears therefore to have emerged from the Jewish sectarians;

- The Josephan passage is polemical, apparently attacking what we associate with the orthodox Christian Pauline baptism that was a ritual performed to effect the forgiveness of sins and new spiritual life. (The Pauline and gospel baptism — especially as in the Gospel of Matthew — has nothing to do with physical purity.)

- Origen appears to have not known of the John the Baptist passage in Josephus but we first read of awareness of it in Eusebius. We can conclude that the passage was inserted by a member of one of the early Jewish-Christian sects late third or early fourth century.

-o-

To refresh your memory, here again is the Josephan passage with the description of his baptism highlighted:

| But to some of the Jews the destruction of Herod’s army seemed to be divine vengeance, and certainly a just vengeance, for his treatment of John, called the Baptist. For Herod had put him to death, though he was a good man and had exhorted the Jews who lead righteous lives and practice justice towards their fellows and piety toward God to join in baptism. In his view this was a necessary preliminary if baptism was to be acceptable to God. They must not employ it to gain pardon for whatever sins they committed, but as a consecration of the body implying that the soul was already thoroughly cleansed by righteousness. When others too joined the crowds about him, because they were aroused to the highest degree by his sermons, Herod became alarmed. Eloquence that had so great an effect on mankind might lead to some form of sedition, for it looked as if they would be guided by John in everything that they did. Herod decided therefore that it would be much better to strike first and be rid of him before his work led to an uprising, than to wait for an upheaval, get involved in a difficult situation, and see his mistake. Though John, because of Herod’s suspicions, was brought in chains to Machaerus. the stronghold that we have previously mentioned, and there put to death, yet the verdict of the Jews was that the destruction visited upon Herod’s army was a vindication of John, since God saw fit to inflict such a blow on Herod (Ant. 18.116-19). |

Not a Jewish Pharisaic Baptism

Nir sets aside any possibility that the account of John’s baptism as quoted above could be a typical Jewish Pharisee baptism of the time. The Pharisaic baptism, she explains, was entirely for the purpose of cleansing the body from ritual impurities — from contact with a corpse, skin diseases, bodily discharges, and such. It had nothing to do with moral purity or righteous behaviour. To achieve forgiveness for spiritual sins one had the sacrificial cult of the Temple.

What about those passages in the Prophets that speak about washing away sins? One of many examples:

Wash yourselves; make yourselves clean; remove the evil of your doings from before my eyes; cease to do evil, learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow’ (Isaiah 1:16-20)

Some scholars have speculated that such passages were interpreted by some Jews of the day as the basis of a new baptismal ritual, one that requires repentance and spiritual purity before being immersed in water:

The similarity between the initial immersion of the Qumran community and John’s immersion probably stems from a common use of the book of Isaiah. Thus, the idea that one could be made clean in body only if one was pure in heart is probably to be derived from an interpretation of the book of Isaiah that was current among several groups in Second Temple Judaism. (Taylor, The Immerser, 88)

Such passages as these attest the early association between physical and moral purification, such as meets us in the Johannine baptism. And the ideas are close. Whoever invented the epigram “ Cleanliness is next to Godliness,” it is a fair summary of Pharisaic conceptions on the subject under discussion. (Abrahams, Studies in Pharisaism, 41)

Entirely speculative and contrary to the extant evidence, replies Nir. Jewish Pharisaic baptism was for the purification of the body “from natural and unavoidable states of impurity, such as contact with a corpse”. It was not “conditioned on inner moral repentance or spiritual purification.” (p. 53) The passages in Isaiah, the Psalms, Ezekiel, Jeremiah speaking of being cleansed or washed from sins are figurative. (I would add that such passages, if interpreted as the basis of a baptism ritual, would be more likely to prompt a baptism that is contrary to the one described in Josephus’s Antiquities because those passages speak of “washing away sins”, being “cleansed from sin” — as if the washing itself performs the moral purification.)

Yes, Philo did compare physical impurity with moral impurity, but at the same time he recognized the place of sacrifices in moral cleansing.

What of the Essenes and that hermit mentioned by Josephus, Bannus?

In War 2.119-61, Josephus describes the immersions of the Essenes. They bathed in cold water (άπολούοντοα τό σώμα ψυχροΐς ϋδασιν) for ‘purification’ (εις άγνείαν), and would wash themselves before meals (129), following defecation (149), or contact with a Gentile or person of inferior status in the sect (150). About Bannus, an ascetic hermit who lived in the wilderness, Josephus recounts that he would wash himself frequently in cold water, by day and night, for purity’s sake (λουόμενον πρός άγνείαν, Life 2.11) (Nir, 55)

That is, baptism for both is

- self-administered

- daily

- in cold water

- for physical purification

and Josephus uses similar terms for both.

With the support of an article by Bruce Chilton Rivka Nir observes of the baptism found here:

It has nothing to do with prior repentance or moral and spiritual purification: its administration requires no preaching or urging; it is no collective mass baptism and does not constitute an initiation rite into some elect group. Furthermore, the Essene and Bannus immersions were not a substitute for the sacrificial cult.

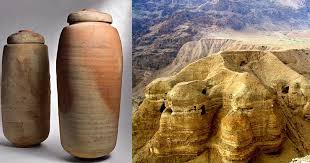

It may not be an “orthodox” Jewish baptism of the era, but Rivka Nir does see an overlap between the Josephan account and what we read in the Qumran scrolls. The key text is the Community Rule (dated by orthography and paleography between 100 BCE and 50 CE).

A Jewish-Christian Baptism

Rivka Nir’s argument is that Jewish sectarian baptisms stressing moral purity as a condition for ritually cleansing the body by immersion existed side by side early Jewish-Christian sects in opposition to the Christian baptism known to us from the Pauline tradition.

We start with the evidence for Jewish sects having a baptism in parallel with what we read about John’s in Josephus.

Qumran scrolls

In the Community Rule 1QS 2.26-3.12 we see the same type of baptism that Josephus depicts for John — ritual cleansing of immersion into water is effective if one is first repentant:

And anyone who declines to enter the covenant of God in order to walk in the stubbornness of his heart shall not enter the community of his truth … For it is by the spirit of the true counsel of God that are atoned the paths of man, all his iniquities, so that he can look at the light of life. And it is by the holy spirit of the community , in its truth, that he is cleansed of all his iniquities. And by the spirit of uprightness and of humility his sin is atoned. And by the compliance of his soul with all the laws of God his flesh is cleansed by being sprinkled with cleansing waters and being made holy with the waters of repentance. May he, then, steady his steps in order to walk with perfection on all lhe paths of God, as he has decreed concerning the appointed times of his assemblies and not turn aside, either right or left nor infringe even one of all his words. In this way he will be admitted by means of atonement pleasing to God, and for him it will be the covenant of an everlasting Community.

Also as with the Josephan baptism of John we see the effect at a community level.

At Qumran, as in John’s baptism, justice (righteousness) was the means to purification and expiation of sins . . . And like John’s baptism, the Qumran baptism appears to have been one of the conditions for admission to the congregation: and it was similarly a collective baptism and a substitute for the sacrificial cult. (Nir, 60)

Also the Fourth Sibylline

Another Jewish group, one responsible for the Fourth Sibylline (dated to about 80 CE), takes the same position: Continue reading “John the Baptist — Another Case for Forgery in Josephus (conclusion)”