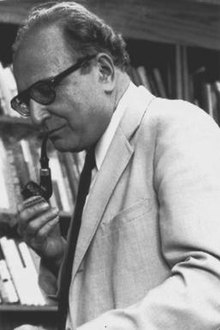

Trying to understand what is happening in the United States has led me to new areas of reading, including The Politics of Unreason: Right-Wing Extremism in America, 1790-1970 by Seymour Martin Lipset and Earl Raab. The opening paragraph of the Preface to that book:

This particular analysis of right-wing extremism in America began to emerge in reaction to the McCarthyism of the early 1950’s. Lipset’s article attempting to place that phenomenon in a historical and sociological context was the first to apply the concept of the “radical right” to American social movements.1 That article briefly surveyed some of the earlier movements from the Know-Nothings to the Ku Klux Klan, and pointed to ways in which American values made for a greater degree of political intolerance here than in other relatively stable democratic countries. (p.xv)

1. S. M. Lipset, “The Radical Right,” British Journal of Sociology, I (June1955), pp. 176-209 . . .

So back to the 1955 article I went as my starting point. The first part of the article posits several “sources of right-wing extremism in American society”.

Status and Class Politics

Class Politics: During periods of economic depression political movements or parties seeking economic reform, a redistribution of income, have gained the upper hand.

Status Politics: Periods of prosperity, full employment, with many able to improve their economic position, we have the rise of those seeking to preserve the status quo. As groups aspire to maintain or improve their social status conflicts ensue. Some groups feel frustrated at being excluded and others feel their status is threatened by new aspirants.

Enter Scapegoats

The discussion is about status politics. (Of course, in 2016 we had economic growth but at the same time many were being left behind. This was surely a significant difference from 1955.)

The political consequences of status frustrations differ considerably from those resulting from economic deprivation, in that there is no clear-cut political solution for the problem. There is little or nothing which a government can do to relieve these anxieties. It is not surprising, therefore, that the political movements which have successfully appealed to status resentments have been irrational in character, that they focus on attacking a scapegoat, which con- veniently symbolizes the threat perceived by their supporters.

Who are the scapegoats? They are ever the same . . .

Historically, in the United States, the most common scapegoats have been the minority ethnic or religious groups. Such groups have repeatedly been victims of political aggression in periods of prosperity for it is precisely in these times that status anxieties are most pressing.

Compare today, immigrants especially from the south, and Muslims.

Scapegoats: the historical pattern

Before the Civil War there was widespread anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiment throughout the nation (e.g. the Know-Nothing or American Party)

Late 1880s, another period of prosperity, another anti-Catholic movement, the American Protective Association (A.P.A.).

Latter day Know-Nothingism (A.P.A.ism) in the west, was perhaps due as well to envy of the growing social and industrial strength of Catholic Americans.

In the second generation American Catholics began to attain higher industrial positions and better occupations. All through the west, they were taking their place in the professional and business world. They were among the doctors and the lawyers, the editors and the teachers of the community. Sometimes they were the leading merchants as well as the leading politicians of their locality. (Humphrey J. Desmond, The A.P.A. Movement, 1912, pp. 9-10)

1920s saw the height of the Ku Klux Klan (the 1930s Depression saw its relative demise).

1900-12, another period of high prosperity, the Progressive Movement.

Richard Hofstadter has suggested that the movement was in large measure based on the reaction of the Protestant middle class against threats to its values and status. On one hand, the rise of the “robber barons”, the great millionaires and plutocrats of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, served to threaten the status of many old families, upper middle class Americans who had previously considered themselves the most important group in society. Their position was challenged by the appearance of the new millionaires who were able to outdo them in philanthropy and in their styles of life. On the other hand, this movement, like previous expressions of status politics, was opposed to immigration. It viewed the immigrant and the urban city machines based on immigrant support as a basic threat to American middle-class Protestant values. The Progressive movement had two scapegoats—the “plutocrat” millionaires, and the immigrants. (pp. 178f)

Lipset was able to write that protest movements arising out of economic depressions lack scapegoats. Scapegoats are attacked when people see a threat to “the American value system rather than its economy.”

And it is this concern with the protection of traditional American values that characterizes “status politics” as contrasted with the regard for jobs, cheap credit, or high farm prices, which have been the main emphasis of depression “class politics”. (179)

It is interesting to reflect on the above in the light of the more complex economic situation since 2016 and the dramatic change in economic hopes since the COVID-19 crisis in 2020.

The State of Tolerance in America

Depressingly, Lipset was able to write in 1955

The historical evidence, some of which has been cited above, indicates that, as compared to the citizens of a number of other countries, especially Great Britain and Scandinavia, Americans are not a tolerant people

Australians as a whole seemed to be far less tolerant of minorities than they are today, too. Dramatic social changes were spawned in the 1960s and we continue to see greater openness, acceptance, of those who were once excluded. Yet there also lies the problem. Europe also saw a rush of enlightened values in the 1920s only to have them met by the intolerance of extreme right-wing movements.

We know the deprivations imposed on German and Japanese Americans during the two world wars.

Political intolerance has not been monopolized by political extremists or war-time vigilantes. The Populists, for example, discharged many university professors in state universities in areas where they came into power in the 1890’s. Their Republican opponents were not loath to dismissing teachers who believed in Populist economics. Public opinion polls, ever since they first began measuring mass attitudes in the early thirties, have repeatedly shown that sizeable numbers, often a majority, of Americans oppose the rights of unpopular political minorities. In both 1938 and 1942, a majority of the American public opposed the right of “ radicals ” to hold meetings. (p. 180)

One explanation for this special degree of American intolerance has been “the basic strain of Protestant puritanical morality which has always existed” in the U.S.A.

Americans believe that there is a fundamental difference between right and wrong, that right must be supported, and that wrong must be suppressed, that error and evil have no rights against the truth. This propensity to see political life in terms of all black and all white is most evident, perhaps most disastrous, in the area of foreign policy, where allies and enemies cannot be grey, but must be black or white. And it is also evident in domestic politics. (p. 180)

Outsiders like myself cannot help but be somewhat bemused by the sometimes extreme vitriolic rhetoric with which two main parties with comparatively very little daylight between them have been denounced. I attempted to frame that previous sentence in a way that lay responsibility on both sides, but that is not the situation today. Extreme right-wing groups, including the President, regularly denounce Democrats as if they are the very embodiment of anti-American traitors seeking to destroy the nation economically, politically, ideologically.

The differences in fundamental economic philosophy and way of life between the Democrats and Republicans in America are far less than those which exist between Conservatives and Socialists in Great Britain. Yet political rhetoric in this country is on a level comparable only to that used in Europe in campaigns between totalitarian and their opponents. While McCarthy has indeed sunk American political rhetoric to new depths, one should not forget that his type of invective has been used quite frequently in American politics. For example, Roosevelt called some of his isolationist opponents, “Copperheads”, a term equivalent to traitor. If various impressionistic accounts are to be believed, many Republicans, especially Republican business-men, have a far deeper sense of hatred against Roosevelt and the New Deal, than their British or Scandinavian counterparts have against their Socialist opponents.

Lipset further sees a “lack of aristocratic tradition in American politics” as a contributing factor to extremist rhetoric in politics.

Almost from the start of democratic politics in America, the political machines were led by professional politicians, many of whom were of lower middle class or even poorer origins, who had to appeal to a relatively uneducated electorate. This led to the development of a campaign style in which any tactic that would win votes was legitimate. Thus, Jefferson was charged with “ treason ”, with being a French agent before 1800, and Republicans waved the ” bloody shirt ” against the Democrats for many decades following the Civil War. In order to involve the masses in politics, politicians have resorted to attempting to make every election appear as if it involved life or death for the country or specific strata.

Then it was crying wolf. In 2020 I think there really are wolves at the door.<

Then Lipset wrote of the regular factor of “mass immigration”. We know the role migrations through the southern border, as well as immigrants from Muslim nations, have played in the 2016 election. But Lipset here raised a perspective that I had not quite grasped the same way before — the nature of “Americanism”.

Americanism as an Ideology: Un-Americanism

A third element in American life which is related to present political events is the extent to which the concept of Americanism is an ideology rather than simply a nationalist term. That is, Americanism is a creed in a way that “Britishism” is not. The notion of Americanism as a creed to which men are converted rather than bom stems from two factors :

first, our revolutionary tradition which has led us to continually reiterate the superiority of the American creed of equalitarianism, of democracy, against the old reactionary monarchical and more rigidly status-bound system of European society ;

and second, the immigrant character of American society, the fact that people may become Americans—that they are not simply born to the status. While foreigners may become Americans, Americans may become “un-American”.

This concept of “un-American activities”, as far as I know, does not have its counterpart in other countries. American patriotism is allegiance to values, to a creed, not solely to a nation. An American political leader could not say, as Winston Churchill did in 1940, that the English Communist Party was composed of Englishmen, and he did not fear an Englishman.

Unless one recognizes that Americanism is a political creed, much like Socialism, Communism or Fascism, much of what is currently happening in this country must remain unintelligible. Our national rituals are largely identified with reiterating the accepted values of a political value system, not solely or even primarily of national patriotism. For example, Washington’s Birthday, Lincoln’s Birthday, and the Fourth of July are ideological celebrations comparable to May Day or Lenin’s Birthday in the Communist world. Only Memorial Day and Veteran’s Day may be placed in the category of purely patriotic, as distinct from ideological, celebrations. Consequently, more than any other democratic country, the United States makes ideological conformity one of the conditions for good citizenship. And it is this very emphasis on ideological conformity to certain accepted common political values that legitimates the campaigns to locate the “un-Americans” in our midst. (pp. 181f – my formatting)

Now that explains a lot, at least to me. Outsiders may roll their eyes with some bemusement at the way Americans seem to “go over the top” with their expressions of nationalism but the above puts those expressions in a dangerous perspective.

There is much more to Lipset’s article, of course, but the above are the points that held special interest for me by way of background to come to terms with understanding what seems to be a very serious threat to the world should the election later this year go the way Trump is working towards.

Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1955. “The Radical Right: A Problem for American Democracy.” The British Journal of Sociology 6 (2): 176–209. https://doi.org/10.2307/587483.

Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Earl Raab. 1970. The Politics of Unreason: Rightwing Extremism in America, 1790-1970. Patterns of American Prejudice Series ; v. 5. New York: Harper & Row.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Thomas Frank has recently published on Populism and its foes in the US:

http://americanempireproject.com/blog/a-brief-history-of-anti-populism/

Your link to Thomas Frank’s extract from his book leaves part of my post exposed. I began the paragraph on the Progressive (Populist) movement with

In the context of Frank’s account I should restore Lipset’s sentences preceding the above:

According to Frank the progressive movement was not necessarily intolerant, as there were efforts to unite people along class lines rather than by race or ethnicity:

[quote]Populism’s strategy for taking on the region’s one-party system, as Woodward described it, was to organize “a political union” between white and “Negro farmers and laborers within the South,” a shocking affront both to racist tradition and to the interests of the local moneyed class. The Pops, Woodward continued, “ridiculed the clichés of Reconciliation and White Solidarity.”

The bolder among them challenged the cult of racism with the doctrine of common action among farmers and workers of both races.[/quote]

And also this:

[quote]Toward immigrants themselves the People’s Party was remarkably open. A granular investigation of the attitudes of Kansas Populists toward immigrants found precisely the opposite of what present-day theorists insist is always the case with populism. Kansas in the 1890s was a state filled with just-arrived people, and the Populists competed vigorously for their votes; Populist officeholders, meanwhile, came from Ireland, Germany, Sweden, and so on.[/quote]

Like a lot of things it would appear this movement is more complex than it might seem.

The point is Hofstadter’s suggestion of an underlying values conflict at a prosperous moment. Even Frank at least concedes there were certainly racist and intolerant elements among the Progressives. “Movement” might be a difficult word to define in this context.

— Or perhaps Hofstadter was wrong. And so was Lipset in that case.

Another comparison between Trump’s populism and the populism of Bryan’s Progressive movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century period appears in Richard Conley’s recently published Donald Trump and American Populism:

. . .