Barrett next raises what he sees as “reflective problems for atheists“. (For Barrett’s meaning of the term “reflective beliefs” see the opening post in this series: Gods (An Anthropology of Religion Perspective) and its specific application to belief/nonbelief in God, Argument for God — part 1.)

Barrett next raises what he sees as “reflective problems for atheists“. (For Barrett’s meaning of the term “reflective beliefs” see the opening post in this series: Gods (An Anthropology of Religion Perspective) and its specific application to belief/nonbelief in God, Argument for God — part 1.)

Barrett appears to be suggesting that an atheist must in some sense fight against his or her nature in order not to believe in god/s:

In addition to reinterpreting nonreflective beliefs that suggest superhuman agency, atheism requires combating conscious, reflective arguments for theistic thought. In some ways, the burden for certainty is greater for atheists than for theists. (111)

That last sentence is also problematic. “Burden for certainty”? But let’s continue.

Barrett quite rightly points out that the thrust of his explanations for why people believe in god/s or the supernatural of some kind indicates that belief is fundamentally easy. It would hardly be an explanation for the universal belief in the supernatural otherwise, though, would it! People do not need to “work hard” to figure out reasons why they believe. But then,

Given the sort of experiences they have, including the suggestion from others that God does exist, belief enjoys such rich intuitive support that no justification seems necessary. (Perhaps this is why some believers are such easy marks for those college professors that are hell-bent on dissuading them of their faith. They have few if any explicit reasons they can articulate for belief.) Atheism, on the other hand, has less in terms of intuitive support but brings more explicit rationale to the table. As a more reflective belief system, frequently intellectually discovered, atheism has more reflective opportunity for being challenged (as well as encouraged). Hence, explicit reasons for theism generally require some attention from the atheist. (111 – my bolded highlighting)

I can agree with all of that; I can even agree with those “college professors that are hell-bent” on demanding intellectual rigour from their students. In my journey out of belief, the last bastion I was left to face was my conviction that the Bible was “true” in some theological sense. Yes, I needed to address the explicit reasons for that belief just as I had had to address the explicit reasons for each other grounds for belief up till that point.

Reasons believers typically advance for their conviction that God exists are the need for agency to explain the existence of the universe and design in the world around us. Until the arrival of “Darwinism”, Barrett notes, atheists had no real “satisfying defense against their own intuitive sense that the world was designed and the congruent claims of theists.” That may be so. But I am reminded of a time when thunder was universally believed to be the noise of divine or spirit activity of some sort, according to some of our ancient records. And how for a long time planets strangely wandered in their idiosyncratic pattern — as if (how else?) moved by some divine or spirit agent.

Meanwhile, Barrett points out that Darwinism does not address “the origin of life or the mechanical fine-tuning that many astronomers and physicists have recently noted… (Leslie 1982, Leslie 1983, Carter 2002)”. Yes. There is still more to learn. Explaining thunder was but one of the first steps.

Then Barrett returns to his concern for “certitude”:

Atheists may also have epistemological difficulties that theists (depending on theology) do not have. Theists may confidently hold reflective beliefs operating under the assumption that their mind was designed by an intelligent being to provide truth, at least in many domains. For the atheist, another explanation for the certitude of beliefs must be found, or certitude must be abandoned. If our very existence is a cosmological accident and our minds have been shaped by a series of random mutations whittled by survival pressures (not necessarily demanding truth, only survival and reproduction, as a rat, fly, or bacteria can pull off with their “minds”), then why should we feel confident in any belief? And if we can’t feel confident in our beliefs, why do we go through life pretending we can? These questions may have satisfactory answers. The point is that unlike the theist, the atheist has far more explaining to do. This, too, makes atheism harder. (112 — again, my bolding)

I certainly have no problem accepting that our brains have not evolved in such a way that will enable them to grasp a complete understanding of everything we would like. I know quantum physics and even advanced maths are beyond my abilities to comprehend fully. I am quite prepared to accept that the noises I hear my old wooden house at night are the result of contraction from temperature drops, but I am not going to launch a crusade if one day we discover some other mechanism for the noises. In other words, all “certitude” is provisional — we are always open to learning more, revising the old, even discarding it, and moving on. That kind of provisionality as the bedrock is what has enabled us to survive at all, I suspect — not any unqualified or unquestionable “certitude”.

Returning to thunder. Yes, a naturalist has much more explaining to do than the person who attributes the noise to Hephaestus or Zeus or some other divine activity. Why should that be a problem? A child can readily imagine a monster at night; it takes some “reflective activity” to think of plumbing and other noises as the temperature drops. Not every rustle in the grass is caused by a stalking tiger.

Fighting Back Theism

“Fighting Back Theism” is a heading chosen by Barrett. For me it conjures images of the rebellious, renegade atheist fighting wilfully and desperately against the God he “knows” (or “wishes not”) to exist yet also hates. For Barrett,

Atheism just requires some special conditions to help it struggle against theism.

Barrett lists four strategies atheists deploy to “fight” against their “natural” “theistic tendencies”. (There are lots of “natural” tendencies in my mind and body — note the dualistic irony there — that I have been taught and learned to fight against and I think both society and me are the better off for that.)

Strategy 1: Consider Additional Candidates for Belief

We have mentioned “Darwinism”. Barrett returns to evolution as an explanation for how much of the world is and concludes

The agency of God was systematically replaced by the agency of natural selection. And I do mean agency. One of the embarrassing realities for evolutionary theorists is the difficulty of consistently thinking or talking about natural selection without using mental-states language. At an implicit level, natural selection amounts to a sanitized and scientifically sanctioned “god” that may displace God. (113)

Yes indeed. Evolutionary explanations do so often use the language of mental states. Our desire to avoid predators made us faster, harder to see, more intelligent, etc. So we evolved wings “for the purpose of” escaping predators. Decent science books will also make it clear that such language is simplistic, even sometimes metaphorical. That is indeed witness to the power of our “mental tools” and HADD in particular, but acknowledging this tendency does not really imply we are being dishonest and fighting against the evidence, surely. On the contrary, if there is any mental fight its goal is to maintain honesty.

Besides, is there really anything negative to be said about “considering additional candidates for ‘belief'” in any circumstance? Would a just (and non-narcissistic) God seriously condemn “strategy 1”?

Strategy 2: Reduce Theism-Consistent Outputs from Mental Tools

That strategy sounds to me like one that should be commended — as long as the alternatives are amenable to scientific testing. Their answers might be wrong, but we would at least be on the voyage to truth if we continue that way and steadily eliminate the explanations that fail scrutiny.

Barrett says this atheistic strategy has two punches:

a. reduce urgent situations: HADD, recall, is especially active in moments of urgency. No atheists in foxholes? Similarly, no atheists in situations where one’s livelihood depends on subsistence hunting or on agriculture where one’s decisions directly impact on one’s ability to support one’s family. It’s harder to be an atheist when in poverty, Barrett strongly intimates. So a wealthy and comfortable existence is likely to lead to more atheists. Ah yes, the lesson of Lazarus and the rich man.

b. hide non-human agency: Being immersed in an urban culture is conducive to atheism, Barrett affirms. That is, hiding oneself from “wilderness or natural systems” encourages atheism.

Strategy 3: Reduce Secondhand Accounts That Might Become Evidence for God

Recall the Doug story in the previous post. Barrett writes,

Avoiding religious people altogether so that you do not hear their stories would help avoid troublesome “evidence” that seems to support God. (114)

I don’t think atheists like myself avoid religious people in order not to hear such stories as Doug’s. Rather, I think that the conclusions drawn from such stories too often violate the basics of scientific reasoning and it becomes painful to be exposed too often to people who cannot accept and seriously consider alternative interpretations, to people who are too intent on imposing their theistic interpretation on others without serious assessment of alternatives. I have my own favourite stories I used to tell as a believer in divine healing and angelic interventions so I think I know where the theist is coming from.

Another instance Barrett mentions is an account by anthropologist Scott Atran:

Consider one more example. Anthropologist Scott Atran has recounted the following sort of incident in Central America among the Maya people. Bitten by an extremely dangerous venomous snake, a Maya hunter consulted the forest spirits for help. He refused medical aid from the anthropologist and instead “listened” for the forest spirits to tell him which plants to use as a remedy. After consulting the forest spirits, he gathered a few choice plants, applied them, and fully recovered from the bite. In a reportedly common case such as this, a direct appeal to gods is followed directly by great fortune. Concluding that the forest spirits saved the man’s life makes great intuitive sense. Given the way our minds operate, to think anything else would be peculiar and aberrant and require explanation. (55)

So should we see in this narrative evidence for forest spirits? Barrett seems to think so:

But I imagine that most American or European urbanites or suburbanites can easily dismiss the story as a bit puzzling but not worth much careful evaluation. Why not? My hunch is that part of the answer lies not with some inherent incredibility about the event but because the experience of some hunter in Central America has little inherent importance for European or American professionals. We live in a social environment in which there is a great plurality of daily demands and experiences, and consequently others’ experiences are (intuitively) a less important database for evaluating beliefs. (114)

Or is there a possibility that more scientific explanations, explanations that draw upon a vast array of human experience and observation that can be brought to bear upon the Mayan story, hold explanations that tend to be more scientifically verifiable and without any need for the reality of a forest spirit?

Strategy 4: Surround Yourself with Ample Opportunities for Exercising Reflective Thought

Barrett’s fourth strategy: It is reflective thought that overrides nonreflective tendencies that so easily enable belief in deities so it follows that environments that allow for more opportunities for reflective thought are more likely to see atheistic. I find it somewhat odd that Barrett describes such a social system as a “strategy” “for fighting theistic tendencies.”

Barrett illustrates how reflective thought might “fight against” theistic tendencies in such environments:

In these reflective environments, events and phenomena that might encourage theism may be handled with cool consideration, and alternative frames of reasoning may be developed. For example, alleged “miracles” or acts of God may be relabeled as simple chance occurrences, for although “chance” does not qualify as a satisfactory nonreflective explanation, with proper statistical and probabilistic training, “chance” can go a long way toward avoiding needless hypothesizing about why something happened in the reflective mode. Similarly, medical “miracles” or what might be seen as the healing power of a god could be reexplained in the terms of medical science. Those events that may be truly explained could be reflectively explained with no appeal to deities. Those that cannot truly be explained might be labeled in appropriate jargon suggesting that they need not be explained, as in cases of spontaneous remission or placebo effects. (114-15)

Surely this is special pleading. Does Barrett not believe in chance at all? Does he really think so little of science that he considers it an “alternative explanation” for healing? Does he seriously think that someone who concedes ignorance rather than appeal to God for an answer is somehow biblically arrogant?

Why Atheism Is Where We See It

Compared with the near inevitability of theism, atheism appears to lack the natural, intuitive support to become a widespread type of worldview. (115)

It is surely our reflective thought that has been the main tool to bring us out of the stone ages. Unfortunately, this sentence is not meant as an argument for spreading enlightenment and scientific values through various forms of education.

For Barrett, atheism has had something of a notable surge in areas of Europe and North America in the last fifty years. Barrett rejects the “atheists’ explanation” for this emergence, that atheism has become more widespread with the rise of “scientifically and technologically advanced societies and its prominence in nations with strong education systems.” This explanation, Barrett says,

strokes elitist egos . . . (115)

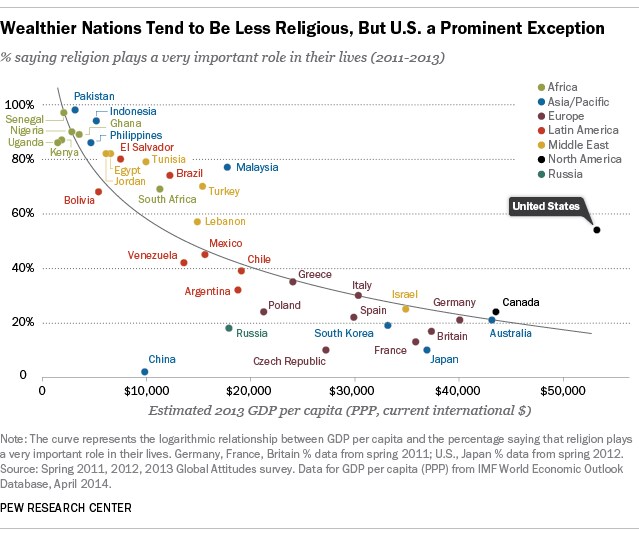

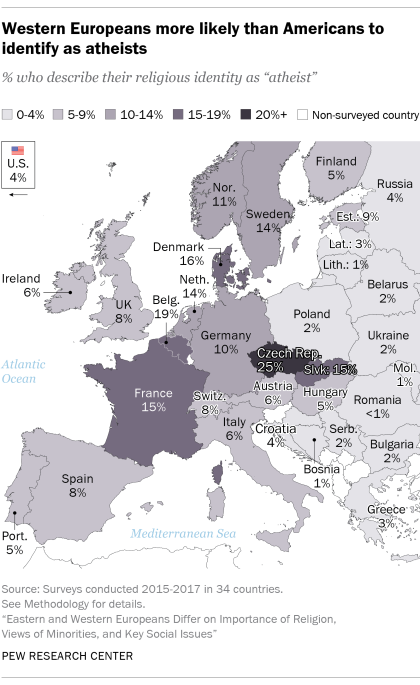

There’s a bit of ad hominem for you. No, says Barrett, look at the United States, a very highly educated nation, but one with a notably “high rate of theism”. Besides, according to the International Social Survey Program (1991), there is only a “weak correlation between atheism and education within Europe, Canada, and the United States.” Further, look at all the philosophers and scientists in the world who “are theists” (115). Barrett does not address reasons for the United States being an outlier in such comparisons. Compare, for instance, the following charts:

Again Barrett introduces a defensive ad hominem:

Formal education does impact the success of atheism, but the relationship is not the simple “only dumb people believe m God” that seems so common among academics.

A crutch for the poor, suffering, and disenfranchised?

While Barrett acknowledges some truth to the claim commonly heard since Marx and Freud that religion is a comfort for those in dire circumstances (where living standards have improved religious belief has also declined) but is quick to point out that this cannot be a satisfactory explanation for religious belief. After all, he points out, religion has another side to it:

However, this account ignores the fact that religion also has the ability to terrorize and oppress. The promise of heaven may make death less threatening, but what about hell? Morality, poverty, and suffering may be related to religious commitment but with more nuance than the “religion as a crutch” hypothesis suggests. (115)

Well, I think one of Barrett’s peers and a very prominent name in the anthropological study of religion, Harvey Whitehouse, answers that particular objection. See Understanding Religion: Modes of Religiosity. Whitehouse suggests that fear-factor is part of the equipment that protects certain kinds of religious modes against the “tedium effect”.

Few walked through the door to atheism until after World War II

Barrett early spoke of a mushrooming of atheism in the “last fifty years” and a page later he pinpoints the period after World War II. Knowing he is a Christian, and even one with a penchant for evangelizing despite his academic integrity in his scholarly publications, am I wrong to wonder if he is somehow suggesting we are living in “the last generation”? Maybe that’s an unfair thought. Barrett’s point is that though there have been “a small number” of atheists in earlier ages,

Before the industrial revolution, atheism almost did not exist. People might have rejected organized religions, but they did not cease to believe in God or gods of some sort, including ghosts and spirits. The industrial revolution opened the door, but few walked through until after World War II. The distinctive characteristics of societies in which atheism seems to have a foothold include urbanization, industrial or postindustrial economies, enough wealth to support systems of higher education and leisure time, and prominent development of science and technology. (116)

Urban settings contribute to atheism in two ways, according to Barrett:

-

- diverse people and perspectives come into close contact; alternative views (reflective interpretations) are more widely shared; people in other parts of a city who claim to have experienced God tend to mean nothing to others who are not in direct contact with them or their lives;

- in an urban environment our HADD (agency detectors) default to detecting human agencies, or the agency of society or the market or the government, etc. Preindustrial societies are more in touch with “the natural world” and how insignificant humans are in the larger scheme of the changes of seasons, weather patterns, plagues, droughts, etc. There is less urgent need to detect a non-human agency for one’s survival in an urban environment.

I think such descriptions are somewhat exaggerated but even if true they are hardly grounds for (reflective) belief in God.

Another exaggeration, I suggest, is when Barrett writes

We’ve all heard the saying that there are no atheists in foxholes. A safer claim is that there are no atheists in the preindustrialized world. Subsistence hunter—gatherers, farmers, and others with traditional, organic lifestyles are almost uniformly theists of one sort or another and always have been. With any distribution beyond a few peculiar individuals, true atheism (the rejection of all superhuman agents, including gods, ghosts, ancestors, demons, and spirits) has occurred only in communities largely divorced from natural subsistence and hence only in industrialized or postindustrialized contexts. On examination, the preindustrialized world and foxholes have much in common to encourage theism: survival-related urgency to make sense of the world, a reliance on natural and not human processes for survival, and being surrounded by apparent agency that cannot be simply attributed to human endeavor or simply ignored. (117)

Yes, moving away from a subsistence existence does allow one more opportunities for reflective thought. If that means that forces we once attributed to spirits are now attributed to physical laws then so be it, and I don’t think Barrett would disagree with that in principle since he goes on to say,

Similarly, having the time to contemplatively consider various ideas does not necessarily lead to atheism. Plenty of atheist scholars have actually reflectively found their way to theism. My point is that the naturalness of religion may be discouraged by the artificial (meaning human-made) pursuit of knowledge.

Barrett is not critical of scientific advances per se. He calls science a “double-edged sword for religious thought”: it has magnified the wonders of the universe but on the other hand. . . .

phenomena previously understood only in terms of the activity of gods now can be understood either in completely naturalistic terms or in some complex combination of natural and divine causes.

I presume that allows for belief in that oxymoron “divinely guided evolution”.

Scientism?

Barrett objects primarily to the way we have come to view science as potentially opening the way to “solving all problems” and “answering all questions”.

Though science cannot really explain why the universe is fine-tuned to support intelligent life or why we should behave morally, perhaps some day it will. This unbridled optimism in the power of science finds faithful followers among many educated citizens of urban Australia, Canada, Europe, and the United States, though professional scientists and philosophers of science tend to be less sanguine than intellectuals a step or two removed from the art. Scientism serves as a reflective safety net for atheists. As I have argued, theists do not believe in God because of apparent design in the universe, but belief in design finds a mutually supportive match with the idea of God. However, issues such as apparent design may be problematic for atheists unless they have a device such as scientism to assure them that even if they do not personally have a satisfactory explanation for apparent design, surely science either has one or will come up with one. (118)

Science may always have its limitations but it surely cannot follow that we should turn back to our nonreflective intuitions.

I found Barrett’s concluding paragraph in this chapter slightly distasteful and littered with special pleading. Perhaps some hypersensitive mental tool of mine — a hyperactive evangelical detection device, “HEDD” (my neologism) — is detecting a subtle evangelical message:

To summarize, atheism has a chance to emerge and spread only among the more privileged members of the developed nations of the world—in Europe and North America particularly. As a testament to its naturalness, even in places where oppressive, totalitarian regimes have tried to crush theism, such as in China or the former Soviet Union, theism remains strong, though hidden, among common folk. Only privileged minorities enjoy atheism. If religion is the opiate of the masses, atheism is a luxury of the elite. This may be especially true of academics not because we are so much smarter (though we like to think so) or so scientifically minded (a higher proportion of physicists than sociologists are theists) but because we enjoy an environment especially designed to short-circuit intuitive judgments tied to natural day-to-day demands and experiences. This is why atheism may seem so natural to those in the academy when evidence suggests otherwise. To adapt a simile from anthropologist and developmental psychologist Larry Hirschfeld, atheist academics marveling about how strange it is for people to be religious is a bit like two-headed people discovering one-headed people and thinking how odd they are. Religious belief is the natural backdrop to the oddity that is atheism. (118 — bolded hightlighting is mine)

I enjoyed Barrett’s discussion of his hypothesis for why it is so easy for us to believe in god/s. I found his argument for belief in God problematic and his arguments relating to the rise of atheism in the modern world to be very limited. (One facet of the question I think Barrett overlooks is the social nature of religions and religious belief, and the evidence that people will profess commitment to beliefs for social reasons while not personally being impressed by those beliefs.) I highly commend that Barrett’s explanations for the ease with which we believe in spirits to be read alongside other cognitive and anthropological explanations such as those by Whitehouse and Boyer.

Barrett, Justin L. 2004. Why Would Anyone Believe in God? Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

There are atheists in foxholes. But even if the aphorism were true, and there were no atheists in foxholes, it would be a better argument against foxholes, against war, than an argument against atheism.

In other words, even though the threat of death may drive some or many to seek aid (real, imaginary, or perhaps fetishistic like carrying a rabbit’s foot) in desperation, that has little to do with whether or not theism is true.

Whenever I see an author who doesn’t understand what natural selection is and conflates it with the origins of life and wants to talk about fine-tuning, I have a hard time listening to anything else they say. Likewise, when they dare to touch on the concepts of morality without confronting how profoundly immoral religion is, they’re either woefully ignorant or intentionally avoiding the problem.

Here is an author who has spent months or years of their life writing a book while pretending to be an expert, yet the lack of expertise is evident. How do I take Barrett (and other authors) seriously when they obviously don’t care enough to learn the basics, or they’re being intentionally dishonest?

This wasn’t a debate where he had to respond to questions on the fly. This was a book, where he had all the time in the world to get it right. Where he could call in experts to help, and have numerous people review it.

And yet he didn’t.

I hate to lean towards malice, but Barrett obviously is a fairly intelligent person and he can write pretty well. It’s hard to give him the benefit of the doubt and assume incompetence when he’s demonstrating so much competence.

Just a quick steer to avoid PEW research as providing any meaningful statistics on religion and atheism. In the UK we had a decade of public policy, particularly BBC programme making priorities, because our census asked “what is your religion?”, 70% of the UK ticked Christian.

If then asked “do you believe in god?” almost all of that 70% said “no, of course not”. 100% of the Jewish population would have answered ‘Jewish’, but fewer than 15% are actual believers.

What our census and Pew measure is religious cultural background. Not belief.

It has been a struggle to get believable stats out of this process but 75% non-believers emerge when you amalgamate all the agnostic, atheist, other non-believers and interrogate how many professing a faith actually believe in a god.

The figure for theists is further inflated by the crystal gazers and others who reply “I don’t believe in god but there must be something.”

7% of our population attend worship but many of those are parents achieving a minimum level of attendance so their children can go to a faith school. Thankfully only 1% of those UK kids between 19-24 identified as Christian.

I am so proud that, despite compulsory religious education and daily act of Christian worship in all schools – yes, our education system is that backward – that 99% of our children have not fallen for Christianity.

Perhaps there is an innate human understanding of the absurdity of deities that leads children to naturally reject them?

Yes, understood that one must always be careful to read exactly what the figure is measuring. Fortunately I have found the polling of Gallup and Pew to be thorough in that the volumes they make available online do fully explain each question, the caveats to be aware of, what is not measured and what is, in each instance. So long as we compare apples with apples I think we get some reasonable valid comparison.

In the tables in the past we have two measures: one is of the view that religion plays a significant role in one’s life, so we know that that figure is of cultural information and not personal devotion or beliefs; but the second table is a comparison of those who “identify as atheists” — that is quite specific.

Re “Reasons believers typically advance for their conviction that God exists are the need for agency to explain the existence of the universe and design in the world around us” I have heard this stated over and over but my experience with ordinary people, vast numbers of them, that they spend no time thinking about these topics, none at all. The people who do think about these things are thee well educated, who have a great deal of time for reflective thought.

Can you imagine a child wondering about “agency to explain the existence of the universe and design in the world around us” at all? Do these questions come up in their secular educations? Only in small contexts in which the explanations for “why?” are readily available (Why do forests exist? Why do mountains exist? Why do lakes exist? Each question followed by the natural history of such.

The only places such questions would arise are in college classes and … in churches.

Actually, it is the Hephaestus-believer who has much more explaining to do: How sure are we that there is really a Hephaestus in the first place? Is he the only possible cause of thunder? How and why is he making thunder at all? How confident can we be of an explanation if there is no way it could be falsified, and a contrary one fits the evidence just as well?

To state the obvious: The fervent Christian has similar explanatory mountains to climb.

The religious has no answer to such questions, except “It is forbidden to ask those questions! ”

A search for the true, demonstrable, predictable causes of thunder would generate all kinds of other new, useful information. Tattooing “Goddidit!!!” on your hand and clapping it over the mouth of anyone who posed some interesting question about the natural world could only halt rational investigation.

This whole series has been a parade of elementary errors of logic: Question-begging. Arguments from incredulity. Ad hoc explanations. Ad hominems. Motivated reasoning. Strawmen.

How about this for a reason to be an atheist: If this is the best they’ve got, I’m not impressed.

PSEUDO-SCIENTIFIC BLINDNESS OF ATHEISTIC CLARITY

The reasons for atheism are not in the reasons that are made public, because they are only pretexts. The real motive is that the atheist wants to live without God! Belief in or denial of God cannot be separated from the fact that the atheist’s freedom depends on this choice. “I am content with the choice to be an atheist because I feel more intelligent and free because no one is guiding my choices.” So motivated by a subjective desire for freedom, but with hard moral parameters.

See:

https://darhiwum.blogspot.com/2024/03/pseudo-scientific-blindness-of.html