We have two models for the origin of the biblical and its ancillary literature.

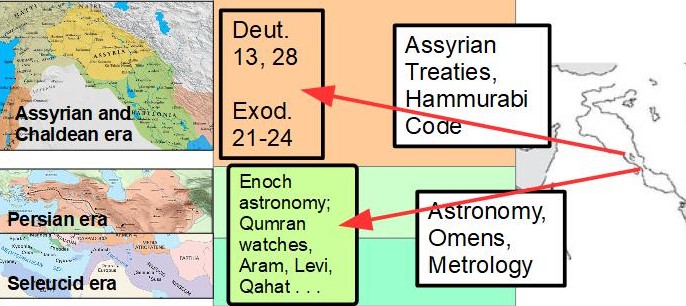

According to Seth Sanders in From Adapa to Enoch we have a progression from the late Iron Age to the Seleucid era.

- The early period (during the time of the kingdom of Judah before its exile) we have “public genres of power” that appear to draw upon the primarily cuneiform law codes and vassal treaties of Mesopotamia. In “Judea” these genres acquired a narrative framework.

- Later, in the postexilic period, we find instead secret genres of knowledge that drew upon the scribal traditions of omens, astronomy, etc. The primary facilitator for this development was the spread of the Aramaic script as a common scholarly language.

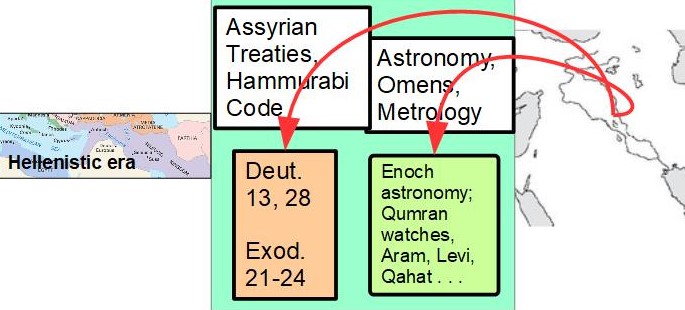

Russell Gmirkin’s view is that the above texts of Deuteronomy and Exodus are rather products of the Hellenistic era. The elements of the political and legal documents of Mesopotamia are relatively few and subsumed within the sort of literature that Plato was promoting in Laws. The narrative framing of such laws was also enjoined by Plato.

Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible does not cover the noncanonical literature so the following diagram is my own, not Gmirkin’s. Throw the stones at me for what follows. I have, however, drawn upon other scholars who also set out reasons for their suspicions that the canonical texts were the product of the Persian and/or Hellenistic eras. (Philip Davies whom I mentioned in the previous post looks largely at the Persian era.)

I imagine that with this latter scenario there are different schools, some of them possibly opposed to each other. The diagram below makes it appear that they are contemporaneous but I do not think that should not be seen as strictly the case.

The diagram also only mentions the same texts as above (law codes and public curses) but that is only for comparison purposes. In fact just about everything from Genesis to Daniel is included here. (Philippe Wajdenbaum in Argonauts of the Desert extends the Greek influence from the legal codes to details of the narrative framework of those laws.) The pseudepigraphical texts are another story.

I am only running through a mind-game here. If there were in fact opposing scribal schools, and if the Greek literature was an influential factor in the formation of what became the canonical texts, do we find a glimpse of the origin of that division in the following passage of Plato’s Laws, Book 7. We know the Pentateuch condemned the study of the stars, but why?

ATHENIAN: Next let us see whether we are or are not willing that the study of astronomy shall be proposed for our youth.

CLEINIAS: Proceed.

Continue reading “More Thoughts on Origins of Biblical and Pseudepigraphical Literature”

I have been posting on points of interest in Seth Sanders’ From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon and have reached a point where I cannot help but bring in certain contrary and additional perspectives from another work I posted on earlier, Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.

I have been posting on points of interest in Seth Sanders’ From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon and have reached a point where I cannot help but bring in certain contrary and additional perspectives from another work I posted on earlier, Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.