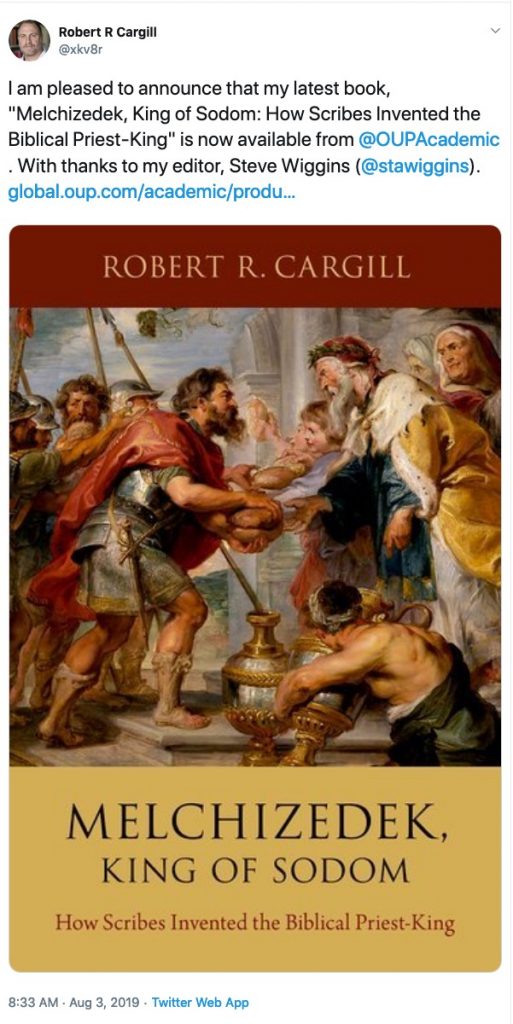

This title caught my eye:

A quick bit of googling brought me up to speed on the general idea. From Melchizedek king of Sodom in Genesis 14? by Matt Colvin:

Now, I am not a higher critic, but I have read the collected works of David Daube, and I have learned that where there are difficulties and ugly seams in a narrative, it is worth digging to see if there is an elegant solution to the problems. I think the following facts require consideration:

1. “Melchizedek king of Salem” appears with no introduction. He is not mentioned anywhere earlier. He is not among the 4 kings on one side or the 5 kings on the other. The chapter is swarming with kings, but the king of Salem is not among them until he is suddenly introduced apropos of nothing.

2. The “king of Salem” is mentioned one verse after we are told that “The king of Sodom went out to meet Abraham after his return…” If the king of Salem is one person, and the king of Sodom is another, then verse 17 shows Abraham meeting the king of Sodom, when suddenly the king of Salem intrudes and gives Abram a blessing. Meanwhile, what is the king of Sodom doing? Just standing around watching this transaction?

3. Why would the king of Salem give Abraham a blessing? The king of Sodom, on the other hand, has just been defeated and plundered by Chedorlaomer and company, so he would naturally be thankful and full of good feelings for Abraham, who has just defeated Chedorlaomer et al. in turn.

4. Further, no sooner has Melchizedek blessed Abraham than the king of Sodom resumes conversation with Abraham as though they had never been interrupted! Such convolutions fly in the face of everything that Robert Alter has taught us about the economy of reported speech in The Art of Biblical Narrative.. And the king of Salem vanishes, never to be mentioned again until Psalm 110:4 (and again in Hebrews 6-7). Abraham and the king of Sodom act like the king of Salem had never been there. They act, that is, as if they are the only two parties present or active.

All these considerations are very old. They have exercised the Rabbis, who give creative solutions.

5. Verse 20 says that “he gave him a tithe of all.” The author of Hebrews of course takes this to mean that Abraham tithed to Melchizedek. But the verb would most naturally taken with the same subject as the previous verbs, which were “And he blessed him and he said…” Furthermore, why would Abraham give tithes to an unknown king?

Imagine… if the king of Salem is actually the king of Sodom, we would have…

1. No interruption of the narrated meeting, but rather, further information given about it: the single king (of Sodom/Salem) is given a name so that we can know who he is before he exchanges words (and would-be gifts) with Abraham.

2. No need for a sudden change of subject (#5 above), since unlike the king of Salem, the king of Sodom has a very good reason to give Abraham a tithe, for Abraham is the victorious conqueror of the conqueror of the king of Sodom.

3. A much better unity to the passage. The discussion of whether Abraham should take the goods and give the king of Sodom the persons follows very naturally on the information that the king gave him a tithe. Recognizing his indebtedness to Abraham, he attempts to pay him with a tenth of all he has, but requests the favor of keeping the persons. Abraham refuses to take anything, just as will also insist on paying for the cave of Machpelah instead of accepting it as a gift from Ephron the Hittite in Genesis 23. He will have no debt-friendships with peoples of the land at all.

4. The word Salem (שלם) is somewhat similar to Sodom (סדם), so that it is just possible that “Salem” is a corruption of “Sodom”. But it may be possible to come up with other explanations for the substitution of the city name Salem for Sodom in verse 18. For instance, Wikipedia notes that W. F. Albright reads “melek-shelomo” = ”a king of his peace”, sc. ”a king allied to him”. It adds, “if the Albright reading is accepted, this would then imply that the whole interchange was with the King of Sodom.” This seems to me a highly desirable conclusion from a narratological viewpoint. (The estimable Jesuit scholar of Aramaic, Joseph Fitzmyer, mentioned Albright’s suggestion here.)

I don’t know if Robert Cargill’s book contains a similar argument but would not be surprised at some overlap.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

That’s an interesting and tidy solution. I’m usually sceptical of emendations of any kind, though, since the text does in fact say שלם and not סדם.

There is a long tradition of emendation to the MT wherever such seams appear, but I always have the suspicion that the very inappropriateness of the text (at least from the perspective of most 20th century critics) is itself evidence of something more reliable than the tidying up that is attempted.

One thing that always sticks out in my memory is in Habakkuk, the anchor bible version by Francis Andersen emended this one verse that said something like “evening wolves” to say “desert wolves”. A slight change in the Hebrew, but that’s the point where I realized such arguments were inherently weak without manuscript evidence. The taste of the critic just isn’t convincing enough since such tastes change constantly.

If it is emended from סדם to שלם, it is emended at an oral level and not scribal.

More difficult is the name ‘Melkizedeq’ without a definite article. We know the king’s name in Sodom: Bera.

So the changes are thoroughgoing.

Are there any ancient orthographies giving סלם here or ha-Melk ha-Zedeq there?

It certainly reads like an edited passage. Perhaps having the King of Sodom give a blessing to Abe was too embarrassing, so a new fictional character had to be invented. Nothing out of the ordinary for Biblical redactors.

Salibi lays out his argument that the passage has been mis-translated. Not a cunning linguist, but it makes sense to me.

Way back in 1901, Herman Gunkel argued that the entire Melchizedek passage, Gen. 14:18-20 was ans interpolation. While Colvin thinks that v.20b (“And he gave him one-tenth of everything”) refers to the King of Sodom giving to Abraham, I think he misses the sacerdotal element: this tenth is equivalent to the priestly tithe, and for this reason seems inextricably linked, conceptually, with Melchizedek’s priestly status. And it doesn’t sit terribly well with verse 21, where he asks Abraham to give HIM the people and take not some, but all the goods. So I agree with Gunkel on this.

I would tentatively suggest that even the reference to Lot looks tacked on, in order to bind this story into the main narrative which places Lot in Sodom. Lot’s role and significance here is minimal, to say the list. Here are verses 11 & 12:

(11) And they took all the goods of Sodom and Gomorrah, and all their provisions, and they departed;

(12) And they took Lot and his goods – the son of Abram’s brother – and departed – and he lived in Sodom.

The final verb of verse 11 completes the raid – “and they departed”. We then backtrack to hear of Lot’s abduction in verse 12. There is a very odd phrase order in this verse, which I’ve reproduced in the translation above, and it looks like an addendum – the repeated word “departed” suggestive of a a resumptive repetion of the same word it the end of verse 11.

Something similar happens in v.16:

(16) And he brought back all the goods – and he also brought back his brother Lot, and his goods, and also the women – and the people.

The reference to Lot seems like an addition here as well (signalled by “and also”). Removing both references to Lot in this chapter does not even slightly damage the the narrative. So, removing Lot and Melchizedek, this is how verses 16-21 read:

(16) And he brought back all the goods […] and the people.

(17) And the king of Sodom went out to meet him, after his return from the slaughter of Khedorla’omer and the kings that were with him, at the vale of Shaveh (ie the King’s Valley).

[…]

(21) And the king of Sodom said unto Abram: ‘Give me the persons, and take the goods to thyself.’

(22) And Abram said…. etc

Which has a clear and neat narrative logic.

Such a small point to belabour about folk that never existed and events that didn’t happen. Perhaps someone should tell him there is no dead horse left to flog – it is long-a-go glue.

Quite right, too! It is a stupid waste of time to ever even think of studying any ancient mythology or beliefs in the supernatural or legends of supra human heroes. Let’s burn or bury all such books and articles and dedicate our resources exclusively on “The Truth!”

The book is not so much the wood for the trees, but “Isn’t this an interesting twig?” while stood in the Amazon rainforest oblivious to it being a man-made environment, gone to seed for neglect, and the archaeology of the civilisation it has overgrown. Let’s get some accurate understanding of the fascinating whole before haring of after trite details. It isn’t yet the time or place for that.

You might not realise what you have accomplished here over the last decade or more. You’ve collected all the weapons and all the ammunition; fired it off; and killed a cod-academic discipline stone-dead. What lingers is a zombie. I am saying rhetorically to the “scholars” so-called: “Alchemy is retired; can we have some Chemistry, please?”. I care probably more than I should about this. 🙂

Well……. Ok……..

If you don’t like what the text says or if you don’t understand what the texts say and the text does not support your assumptions then let us change the text to fit our perceptions of the text.

I like wrestling with the text more then wrestling with a women. My enjoyment is much longer lasting. 🙂