Oh my god. The lies we were taught in school. I have just finished listening to an interview with (v.i.p.) Shashi Tharoor about his book on the British rule of India: Inglorious Empire: What the British Did To India.

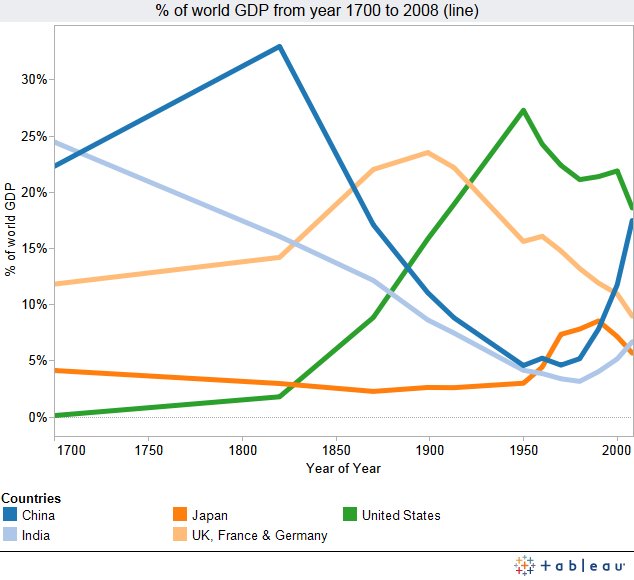

- Before the British arrived India represented over 20% of the world’s GDP (textiles, steel, shipbuilding…) and had done so for centuries. By the time the British left it was reduced to 3% of world’s GDP.

- There is an eyewitness account the British smashing Indian looms and breaking or cutting off the weavers’ thumbs so they could not rebuild the looms and resume production.

- The Indian export textile industry was effectively destroyed as Indians were forced to sell cotton to Britain and then buy back inferior British textiles.

- The railways did little to benefit Indians until after the British left.

An interesting datum given today’s situation…

- The British were the ones responsible for introducing the Hindu-Muslim antagonistic divide. The Hindus and Muslims were united, serving under common native command, to oppose the British. The British responded by initiating policies that over time succeeded in their aim of building hostility between the two faiths — the old “divide and conquer” tactic.

And we are reminded again of the genocidal policies that I first read about in Mike Davis’s Late Victorian Holocausts. This time, however, it was Winston Churchill himself who emerged as the Stalinesque monster, diverting grain from regions where millions were dying in order to build up reserves for remotely hypothetical threats in Europe. Churchill is on record as saying the deaths are the Bengalis own fault for “breeding like rabbits”.

And on and on it goes…..

And we were taught how different the British empire was from any other previous empire. The British empire was a civilizing boon to the world, spreading law and civilization and lifting the standards of living of its subjects.

The only redeeming detail in Tharoor’s account is that there were many British voices who saw the reality of what was happening in their own day and did speak out. But like the anti-war and anti-neoliberalism voices today they were sidelined by those with the power.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I read a book years ago called “The Great Hedge of India”, which was about a hedge/barrier built by the British extending eventually some 2,500 miles across India to control the salt trade in Bengal and other parts. Sections of the hedge exist to this day. The hedge acted to reinforce the British monopoly on salt, allowing exorbitant prices to be charged to the natives. The Salt Laws weren’t finally abolished until the Gandhi revolution.

I wonder if it is going too far to suggest that what Britain did to India is what Trump thought the U.S. should have done to Iraq.

Yes; the British most likely were economically bad for India:

https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2017-04-11/legacy-of-british-rule-is-still-holding-india-back

but the economic decline of India mostly occurred decades before British imperialism became a major force there:

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/seminars/seminars/conferences/econchange/programme/williamsonvenice.pdf

Likewise, the very primitive textile industry of 18th century India was highly labor-intensive, continued well into the 20th century (though in a diminished state), and was a technological dead end. India’s modern textile sector fell behind Japan’s in the early 20th century due to the British being less willing to combat wildcat strikes than the Japanese and India having a more segmented labor market:

https://pseudoerasmus.com/2017/10/02/ijd/

“The British were the ones responsible for introducing the Hindu-Muslim antagonistic divide.”

Nonsense. The rise of the Delhi Sultanate was hardly peaceful.

If you want to read real economic history, search Pseudoerasmus’s tweets and posts.

https://twitter.com/search?f=tweets&vertical=default&q=from%3Apseudoerasmus%20tharoor&src=typd

Have you read Tharoor’s book or do you disagree with some of the points he concludes simply because other works have given different conclusions? Tharoor’s work is certainly an attack on standard views. I’d check out both sides of the arguments before jumping in with a firm opinion either way. Examine the data, the evidence cited for each argument.

“Have you read Tharoor’s book or do you disagree with some of the points he concludes simply because other works have given different conclusions?”

The latter.

Yes; India did shrink as a percentage of world GDP under British rule because Europe, Japan, and the Americas became much richer during the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries, while India’s GDP per capita grew far less. Whether India would have taken the route of Europe, the Americas, and Japan without British rule is an open question, but, as with China, I suspect it was doomed to shrink as a percentage of world GDP regardless of whether its institutions were native or foreign.

Relative rises and falls in global GDP are not the point. . . .

From the book (I have highlighted the critical point responding to your apology.)

Various types of graphs and graphics illustrating global GDP over past 2000 years are set out at https://infogram.com/Share-of-world-GDP-throughout-history

One example:

Another:

FYI, here are the British and Indian real GDPs per capita from the Maddison Project (the red/magenta series are based on within-country data; the blue/cyan series on between-country data; between-country data is collected sporadically):

https://againstjebelallawz.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/countrygdps.png

I think you are missing the point of the argument, no?

I’m not here to argue. I’m here to inform.

The post is about a published argument. You are welcome to provide information that you can demonstrate relates to that argument. Your information completely misses the point. 🙂

(Or perhaps you can inform us how your information relates to the argument presented.)