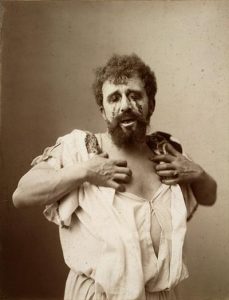

In one of the more memorable scenes in Greek drama, Oedipus reacts to the sudden revelation of his actions by moving off-stage and blinding himself. Critics over the centuries have pointed out the tragic meaning of his inner blindness before, contrasted with his outer blindness afterward. But while Oedipus’s blinding occurs out of sight, a messenger describes the gruesome details.

Jocasta has committed suicide. Oedipus has at long last fully understood the awful truth:

Bellowing terribly and led by some

invisible guide he rushed on the two doors, —

wrenching the hollow bolts out of their sockets,

he charged inside. There, there, we saw his wife

hanging, the twisted rope around her neck.

When he saw her, he cried out fearfully

and cut the dangling noose. Then as she lay,

poor woman, on the ground, what happened after.

was terrible to see. He tore the brooches—

the gold chased brooches fastening her robe—

away from her and lifting them up high

dashed them on his own eyeballs, shrieking out

such things as: they will never see the crime

I have committed or had done upon me!

Dark eyes, now in the days to come look on

forbidden faces, do not recognize those

whom you long for—with such imprecations

he struck his eyes again and yet again

with the brooches. And the bleeding eyeballs gushed

and stained his beard—no sluggish oozing drops

but a black rain and bloody hail poured down.

So it has broken—and not on one head

but troubles mixed for husband and for wife.(Oedipus the King, Sophocles Translated by David Grene)

Some dispute surrounds the etymology of the word “obscene,” although many insist that it comes from the Greek ob-skene — referring to actions such as explicit sex and violence that must occur off-stage. But while the death of Jocasta and the blinding of her son-husband may be obscene to look at, the Greeks apparently did not find them too obscene to describe.

Oddly, however, the death of Jesus in the canonical gospels occurs “on-stage” and “on-camera,” while his resurrection does not occur within the narrative, nor is it described in a flashback. In Mark, generally believed to be the first narrative gospel, Jesus is crucified, and the people pass by, mocking and deriding him. And when he dies, it happens in full view of Jewish and Gentile witnesses.

And yet Jesus’ resurrection does not occur in the flow of Mark’s narrative. It happens with no witnesses. It happens — when? After sunrise? Or in the dark?

The young man at the tomb tells them:

Do not be alarmed. You seek Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has risen; he is not here. See the place where they laid him. (Mark 16:6b, ESV)

Who is the young man? Just as in a fairy tale, the women don’t know, don’t ask, don’t care. How did Jesus rise? Was he instantly elsewhere? Did he rise under his own power? Were angels involved? What happened?

Matthew adds several details, including an earthquake and an angel who rolls away the stone and sits on it. The Roman guards quiver and then pass out. But it seems Jesus has already left the building. The angel says the same thing as Mark’s “young man.” They seek him here, but he is elsewhere. “He is risen.”

Why does the burial scene come to a close, followed by the discovery of the empty tomb? Let’s consider some reasons.

♦ No Witnesses

Those looking for historical reasons for the lack of a description could point to the narrative “fact” that nobody was present to witness the resurrection. The gospels indicate that his followers had left to observe the Sabbath, and that no one returned until Sunday morning. Hence, logically we might assume that with no witnesses, the resurrection had to remain a mystery.

Yet we have other narratives in the gospels in which only Jesus is present. He prays alone at Gethsemane as the disciples sleep. Before walking on the sea, he prays alone on a mountain top. Satan tempts Jesus, even transporting him to different vantage points. These events had no human witnesses, but we have records of what happened. So why was the resurrection different?

♦ A mystery?

Perhaps the mechanics of the resurrection process were part of the inner mysteries of the cult given only to the disciples and certain initiates. Was the soul reunited with the body? By what means?

Did the original myth entail some sort of full transformation into what Paul called “a spiritual body”? Or did that not happen right away? Was he in some weird transition state, leading John to add the story about Jesus asking Mary Magdalene not to hold him? (I have not yet ascended to the Father.)

John, whose risen Jesus actually appears at the tomb, implies that Jesus’ outward aspect after the resurrection may have been different, since Mary did not at first recognize him.

♦ A taboo?

If early followers deemed it a mystery, then a literal, narrative description of the resurrection may have become taboo. They may have even considered it a kind of blasphemy to describe the moment of reanimation and exit from the tomb. This taboo would exist as a powerful tension against the normal requirement for gospel miracle stories to contain amazed witnesses who go and tell others.

Mark’s sole witness can only say that Jesus is risen. Actually, the verb here is in the passive voice, and I’ve fallen into an apologist trap. The correct translation of the Markan passage is: “He has been raised.” To use the present tense of the verb to be with the past participle of the verb to rise allows a certain amount of theological ambiguity; it focuses on the current state of Jesus. But Mark clearly wrote that Jesus was raised, presumably by God.

Some commentators have suggested that the legend of Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead in the Fourth Gospel serves as a stand-in for the “real” resurrection. The audience wants to witness a resurrection scene, and by God, John was going to give them one.

(Note: In the Gospel of Peter, the stone rolls away of its own accord, and two exceptionally tall men enter the tomb. They escort Jesus — also very tall — out of the tomb, and are followed by a talking cross. This seems to be a rather late and obscure legend.)

♦ Theological considerations

According to scholars, the Passion Narrative probably existed before the first full narrative gospel, and that Mark probably used it as a source. They note that the narrative style changes, as the vignettes are longer and become more connected when compared, for example, to the earlier pericopae of Mark, which are brief and often connected only with the introductory adverb, immediately.

The main points of the extended passion story include the entry into Jerusalem, the ruckus at the Temple, the Last Supper, the betrayal, the Trials, and the Crucifixion. But the resurrection itself is merely alluded to after the fact.

On the other hand, the main points of Paul’s kerygma include Jesus death, his burial, the resurrection, and his post-resurrection appearances. These seem to be key features in the Christian confession from quite early on. Yet one of the four corners of Paul’s foundation remains un-narrated and un-depicted in the canonical gospels.

Adelbert Denaux put it this way in “Matthew’s Story of Jesus’ Burial and Resurrection (Mt 27,57–28,20)“:

We discover the four core data of the kerygma in the gospels, even though they have necessarily been broadened and given new emphases. To begin with, it is remarkable how an extensive narrative of Jesus’ passion precedes the short description of his death. In its integration into the passion narrative, the motif of the death is the most strongly developed, both narratively and theologically. Jesus is betrayed, misunderstood, denied, abandoned, arrested, falsely accused, condemned to death, maltreated, ridiculed, robbed of his human dignity, and finally crucified. The cruelty of Jesus’ death is hereby illustrated, but at the same time also made acceptable and “interpreted” in the light of the Scriptures.

At the other end of the four gospels, the motif of the ascension is added by Luke. Mk 16,19 also mentions Jesus’ ascension, but this mention does not belong to the original gospel of Mark; it is a part of the inauthentic ending 16,19-20 being added later. Moreover, an appearance narrative was also lacking in the original gospel (Mk 16,9-18 as well was added later by a second hand); one finds (at most) an allusion to it (16,7).

In the gospels, three out of the four traditional data are described as visible events: death, burial and appearances. One datum is not described, namely the resurrection. This event is communicated, revealed and leaves a negative, ambiguous trace in the world, namely the empty tomb. (Denaux 2002, emphasis mine)

These are just some of the things I’ve been mulling over on this cold Easter day. Your thoughts?

A few other posts on Vridar in which we’ve discussed Oedipus:

- The Young Man in the Tomb in “The Existential Jesus”

- Jesus was no physician

- Are the Gospels Really Biographies? Outlining and Questioning Burridge

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

The event we now perceive as the “crucifixion” was originally the resurrection. It was only reinterpreted as his death, with the iconography following suit later. A simple shift through rewriting. The liturgy of the Holy Week, however, retained some of the cultic representations of the original events. That’s why we don’t find any “resurrection narrative” after the “event with the cross”. The actual death, in this framework, would hide behind the “capture” in Gethsemane.

I have a different theory, but I’d like to hear what other readers have to say before I lay it out.

I wonder if a “resurrection” can really be said to happen in Mark, in a meaningful sense. Sure, Jesus has “been raised”, and he will “appear” to the disciples later; but the “raising” seems more like a Classical epiphane, with Jesus’ body translated to another realm, and the “appearence” could purely visionary (like Paul’s). Maybe Mark’s author meant to be ambiguous about this (and much else) to accomodate conflicting doctrines of his own time; but I don’t really see the need to read later ideas of resurrection into his narrative.

Mark’s presumably original ending has a Twilight Zone-like frisson – “ooh, freaky; what the hell just happened?” – which later gospellers may have been loath to dispel.

Hello Tim,

In relation to Why Does the Resurrection Happen Off-Stage in the Gospels? I agree with all mentioned, of course, only was, if I be at liberty to something would add.

In the section A taboo? you say: Mark’s sole witness… !?

But, I must ask: is it that young man on which has woman would come across in the grave – the witness of resurrection or anything other? More correctly – whether he at all any witness? Maybe he has come there only few minutes earlier – only a little while ago them? Maybe is he would reach the grave for some reason, too, and would find the empty grave? His text likes to me as that is he, towards that what is being would find in the grave, only would CONCLUDE what that happens here – and his CONCLUSION would announce to women and that then looks like the INFORMATION OF HIS CONCLUSION.

Even that young man has been witness of something, he can the only witness of Jesus’ STANDS UP – it is he have said – and no some RESURRECTION! Even has not said neither that the Jesus stands up FROM DEAD, already only that STANDS UP! If the Jesus’ death on the cross has been marked with so many spectacular events, don’t you be supposed to his resurrection that do wake up at least equally – if more – spectacularly? Probably something from this spectacle young man would inform and women, and not just that drily states: He is stand up.

So, I modestly suggests that, towards the text which we have, that young man we cannot call the witness or Mark’s sole witness ! That he anything has seen – even the Jesus’ stand up only – he would say: I have seen him when he gets up and would go – or something similarly!

P.S. Apologize because of my weak English, if notice what mistakes, freely has repaired, I have trust in you, because I am sure that you will understand what actually I wanted say.

Greetings to you and Neil.

Hi Zdenko — Are you saying that the young man in the tomb is not necessarily a witness of the resurrection?

Mark was pauline. So only Paul is the real witness of the Resurrection. The Pillars didn’t witness it. Since even the women didn’t really witness it (so blinding was their fear).

The “offstage” aspect of the resurrection is extended to the state of non-recognition of the actual person of Jesus not only in John, but also in Luke, where his followers have a conversation with him at or toward Emmaus, but their eyes are not “opened” until they break bread with him. This detail positively invites a metaphoric understanding of the resurrection, since the breaking of bread represents taking the word of God, both in the loaves-and-fishes episode, and in the Last Supper (speaking across the four gospels now). In Christian practice (church), it is customary to “smush over” the details so as to allow the mind to do what it does best, namely get to where it wants to go in turns of doctrinal wish-fulfillment. It’s easier to believe in a miracle when you don’t look at it too closely.

The raising of Jesus is off camera because what actually happened (if one believes anything happened at all) was to be kept secret. Namely the corpse was removed so that a substitute Jesus could take over. This would explain why no one in the gospels recognised the ‘new’ Jesus at first sight – he was literally a different man.

Hey, if so many could believe that John the B was a resurrected Elijah and not wonder about how this guy who had been preaching in the neighborhood for some time was suddenly the ‘new’ Elijah then they’d have fallen for anything.

Do not be alarmed. You seek Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has risen; he is not here. See the place where they laid him. (Mark 16:6b, ESV)

Who is the young man? Just as in a fairy tale, the women don’t know, don’t ask, don’t care. How did Jesus rise? Was he instantly elsewhere? Did he rise under his own power? Were angels involved? What happened?

Matthew adds several details, including an earthquake and an angel who rolls away the stone and sits on it. The Roman guards quiver and then pass out. But it seems Jesus has already left the building. The angel says the same thing as Mark’s “young man.” They seek him here, but he is elsewhere. “He is risen.”

/////////////

something which i note (maybe it isn’t anything to note) that matthew needed the women to run off and report, which to me means that matthew did not believe that the angel or the young man in marks account could have done the reporting himself .

Have you read James George Frazer’s “The Golden Bough”? He draws together evidence from a very wide range of sources indicating that the key events of this story – from the entry into Jerusalem to the crucifixion and the belief in his rising from the dead – were one instance of a ritual involving a “fake king” or “king of fools” who would be given authority for a month, cause turbulence, and then be killed as a scapegoat / human sacrifice; and that myths and rituals of this specific form were common across many cultures and particularly present among the Jews of the time. Frazer strongly implies that the only real difference in the case of Jesus is that people afterwards went around saying that this particular case had been the real thing, and that the commonality of the underlying myth was in large part the cause of the rapid popularity of Christianity.

Frazer’s underlying argument throughout the book is that all the classic religions draw their influence from the cycle of the seasons and its influence on peoples highly dependent on agriculture. Since the Industrial Revolution changed that, we can expect such religions to wither or change form – which does seem to be happening with Christianity.

[Ignorant smear against an entire religious group deleted — Neil (Apr 6, 2018)]

I should perhaps clarify: Frazer argues that the historical man Jesus did exist, that he was caught up in the “king of fools” ritual, being named to be that figure for the year, that the common mythic and ritual background across other cultures involved 1) the necessity of the sacrifice of “the king” in order to placate nature and bring life back to the land for the spring, 2) the self-interestedly understandable policy implemented by kings of naming a stand-in for themselves during the period of the year when such sacrifices were expected by the people, 3) the varied historical evidence concerning the real existence of such figures, the varied manner in which they were killed on the sacrificial day, and the common belief that these individuals were incarnations of the various gods whose myths included a belief in their rising from the dead. Therefore the man Jesus or Yeshua was chosen to be the human sacrifice that year, as part of a custom that dated back millennia but was slowly becoming less common. As the sacrificial “temporary king” he would have engaged in behavior common to such figures (Frazer notes recorded examples such as screwing all the king’s concubines for him, handing out the king’s treasury to the poor, making new laws and punishments that no real king would have dared due to having to deal with the long-term consequences).

Thus the entry to Jerusalem becomes an expected and accepted part of the older ritual, the scene with the moneylenders is expected behavior for a king of fools, and the scapegoat’s death is an integral part of the purpose of the whole ritual – to shed the “king”‘s blood and return life to the land thereby. And afterward, Saul could go around saying “no but guys, get this, this time it wasn’t just playacting, IT WAS THE REAL THING” and everybody in that cultural context would know what he meant.

And the resurrection stays off-screen because the whole point of the story is that it’s patterned off other deific resurrection stories that everybody knew – Adonis, Attis, Mithras, etc. So no explanation was needed. It would be like telling a superhero story and taking for granted that he has a secret identity; it’s just part of how those stories are told.

I am catching up with posts and comments and have seen fit to delete your last paragraph in this comment. Read our comments guidelines, Rollory. I see Tim has already put you on moderation. Good. Vridar is not set up as a platform for bigotry.

I think Jesus’ resurrection in the Tomb (which has no witnesses) seems to replace the Holy of Holies for the first Christians. Traditionally, only the High Priest went into the Holy of Holies, and so no one saw what went on there. In Mark, the death of Jesus triggers the tearing of the veil (Mark 15:38), and hence initiates the replacement of the Holy of Holies by the site of the resurrection, which is even more sacred than the Holy of Holies, because while only the high priest saw what went on in the Holy of Holies, no one saw what happened in the Empty Tomb. Josephus records that Pompey profaned the Temple by insisting on entering the Holy of Holies in 63 BCE, so this may have been the impetus for Mark wanting to replace it.

While I’m firmly convinced that there was a highly charismatic Jewish prophet behind the early Jesus movement, I think the Passion story, from the entry into Jerusalem to the empty tomb, is a deliberately constructed allegory that describes the guts of Jesus’ message, the way the authorities tried to kill and bury it, and the fact that they may have succeeded in suppressing the social changes that Jesus was recommending, but the message itself could not be suppressed.

As far as why certain things take place off-stage in Greek plays – do you really expect an actor to put his eyes out so that scene can be presented on-stage?

In the tomb scene the famous Markan sandwich kicks in with a final closing layer pointing to Galilee. The messenger in the white hem only reminds us that Jesus instructed the disciples in chapter 14 to go to Galilee after his raising in order to see him. Even in chapter 13, if genuine another layer, he tells the disciples to run for the hills when tribulations start, that would be Galilee too. The opening layer then would be chapter 1 where Jesus is coming from Galilee to be baptised by John, where he receives the spirit, another form of raising. Voila, sandwich complete.

The deeper meaning of returning to Galilee puzzles me somewhat, but the whole plot sounds like the leader of a gang of lawbreakers instructs them to split up when the shit hits the fan and reassemble at safe home base, Galilee.

my 2 ¢: probably because according to Mark the resurrection is the good news of faith. It’s nothing that the reader should see, but only hear as a message and believe in. Compare with Mark 15:31 So also the chief priests with the scribes mocked him to one another, saying, “He saved others; he cannot save himself. 32 Let the Christ, the King of Israel, come down now from the cross that we may see and believe.” Therefore the appearances are also missing in GMark.

It’s an interesting question. The narrative might even be interpreted as contrived in order to have no witnesses to the resurrection. A comparison with the Gospel of Peter (where the resurrection is described) comes to mind.

Just one detail — a little hobby horse of mine, I know — in response to

The structure of a story told as a series of smaller episodes “strung together like beads on a string” preceding a more developed and fulsome climax at the end is found in several other works of the era: two of the better known examples are Homer’s Odyssey and The Life of Aesop. Such a structure is not always interpreted as evidence that the author took over a preexisting narrative that he redacted in some way for the conclusion to his own work.

Neil said:

I think the lack of witnesses is the whole point of the narrative of the empty tomb/resurrection story in Mark.

Expanding on what I said above, I wonder if Jesus’ resurrection in the Tomb replaces the Holy of Holies for the first Christians? Traditionally, only the High Priest went into the Holy of Holies, and so no one saw what went on there but him.

In Mark, the death of Jesus triggers the tearing of the veil (Mark 15:38), and hence seems to initiate the replacement of the exclusionary Holy of Holies of the corrupt, Roman loving Temple Cult, with the site of the resurrection, which for the Christians is even more sacred than the Holy of Holies, because while only the high priest saw what went on in the Holy of Holies, no one goes in the empty tomb and witnesses what happened in the resurrection.

In this Markan narrative, we see the naked young man (Mark 14:51), representing humans stuck in the perpetual state of the Naked Adam before God, transformed with faith in Christ’s resurrection into a holy state previously reserved for the high priest in the holy of holies. This interpretation assumes the naked, young man (Mark 14:51, representing humans and their endless animal sacrifices – in a perpetual state of being the Naked Adam before an interrogating God), is the same person as the angelic young man in a state of holiness, proclaiming Christ’s resurrection in the Empty Tomb in Mark.

Josephus records that Pompey profaned the Temple by insisting on entering the Holy of Holies in 63 BCE, so this may have been the impetus for the first Christians wanting to replace it.

This doesn’t reflect Jesus’ death as being an atonement for sin, where mankind is thought of as being a perpetually guilty naked Adam in the damning gaze of a Interrogating God, but rather a reinterpretation of the nature of God from ‘Accuser’ to ‘Loving Father,’ who deems as holy and resurrects even a blasphemous, convicted criminal like Jesus.

One last thought. Jesus was certainly guilty of the crimes he was accused of. He was guilty in Rome’s eyes for a number of reasons (e.g., the assault on the money changers in the temple, etc.), and in the eyes of the Jewish high council (e.g., blasphemy). The charges were legitimate, so he deserved to die according to the standards of his day. But the charges were also stupid. Are we not to fight against social injustice as Jesus did with the money changers? The paradox was that Jesus deserved to die, but at the same time was a great person who helped a lot of people. The Christian message was one of a move from God as an accuser that the naked Adam knew, to God as a loving father who saw Jesus as a good holy man in spite of what the world had judged him to be. This has nothing to do with the penal substitution of atonement, but rather the Christians rethinking God and his relationship to humanity.

The key seems to be the disciples of Jesus are perceived as sinners according to the traditional understanding of “God as accuser,” because they followed the soon to be condemned Jesus, and so they fled when Jesus was arrested because they feared for their own lives. Thus, the naked young man was as guilty as naked Adam was before the interrogating eye of God. But the surprise in the story is that the young man is realized to be holy in the end, not just the follower of a condemned criminal. God was not an accuser, but a loving father who sees his children not principally as sinners but as earthly angels.

I think the Gospel of Mark represents a radical re-imagining of the nature of God from the God of the Old Testament and the guilty, naked Adam who was interrogating and accusing (and saw man as a sinner), to one who is primarily a loving father who was not concerned with an endless series of animal sacrifices, but rather judged us according to whether we loved Him and one another. In Mark we read:

My explanation would be that the silence around the actual resurrection is related to the Messianic secret in Mark. And since Mark doesn’t have the story, and Luke and Mark depend on Mark, no other canonical gospel has the story.

According to Wrede, Jesus tries to keep his true nature (as the Messiah) secret from the general public, and his disciples do not understand what they see anyway (in Mark). Only Peter, John and James are let in on the secret. Also Jesus’ prophecies of his own death and resurrection after 3 days, form part of the Messianic secret (Mk 8.29-32, Mk 9.30-32, Mk 10.32-34).

This explains why no crowd, or other disciples, are present to witness the resurrection.

But in this reasoning, you would expect Peter, John and James to be witnesses of the resurrection; I think I heard Robert Price argue that the Epiphany (Mark 1:16-20) started out as a description of the resurrection. This makes a lot of sense to me; the others in the scene, (Moses and Elijah) were both ‘taken up’ to be with God (instead of dying) ,and Jesus appears in white clothes etc. The epiphany is only witnessed by ‘core disciples’, Peter, John, James (and Andrew, only here). As a resurrection appearance, the story makes sense.

In its current location in Mark, the story does not appear to convey much meaning; it is not referred to again in the gospel, and you can skip straight from 1:15 to 1:21, namely, straight from Jesus’ announcement of God’s reign to an illustration of that reign in action, the expulsion of the demonic power from the man in the synagogue.

We can only surmise that a redactor moved the epiphany from post resurrection to a pre-resurrection location; did the epiphany story appear to docetic as a resurrection account? Jesus appears rather ethereal, not corporal (and without injuries from the crucifixion)…..

Heh, Tim

I am waiting for your take on the texts and issues at hand. You mentioned you were going to share your view. Looking forward to it. I may offer a translation of the Mark 16 passage since I have completed a new translation of the NT entitled “Scribe”. In any case I hope to hear more about all this from you and others. It is so intriguing and interesting. Thanks for the posts.

I suppose I shouldn’t give it all away right now, but I think it’s most likely because the Gospel of Mark is circular. If we go back to Galilee (back to the beginning), we revisit the baptism. As Paul said, the baptism is our death and resurrection into new a life in which we are adopted by God. “Behold my son, in whom I am well pleased.”

Perhaps, then, as we read it the second time through, the transfiguration in which Jesus’ clothes become dazzlingly white refers to his exaltation after the resurrection.

But getting back to the baptism, it’s possible that the ritual preceded the myth. If that’s the case, then what happens during the initiate’s rising up out of the water is a personal mystery experience that could not be mythologized.

Oh, of course. The old circularity structure of Mark. Come to think of it, does not that other curious detail about the ending find explanation in the same. I am sure I have read somewhere someone else pointing out that the same circularity was behind the ostensibly bizarre ending of the narrative’s women not telling a soul of anyone in that narrative about the resurrection. It is only the reader who knows what happened. Let the reader understand (again)? The reader is to return to “Galilee”….

It seems that only the reader and the centurion know what’s really going on.

Tim said:

It seems to me the paradox of Jesus being a convicted criminal, but also a righteous martyr (like Socrates, or the impaled noble man in Plato’s Republic), is at the core of the message in Mark. In the death/resurrection in Mark, the three key characters seem to be the women who found the empty tomb, the angelic young man in the tomb, and the soldier at the cross:

(1) The women who are witnesses to the empty tomb leave and tell no one. This seems to be an extension of Mark’s idea that a prophet is not understood by his friends and family (Mark 6:4-6) – as is the cluelessness of the disciples in Mark.

(2) The angelic young man in the tomb seems to be the same young man who was naked earlier in the story. Earlier, the naked young man was as guilty as naked Adam, following a criminal like Jesus. But the young man is made holy by proclaiming the resurrected Jesus, who was a noble Martyr, not a criminal, in God’s eyes.

(3) Justin Martyr seems to suggest that Jesus’ resurrection account is supposed to present him as an alternative (or at least equal) to the Caesars. Justin writes:

Mark picks up on this theme by beginning his gospel with a spoof on a piece of Augustan propaganda. Randel Helms writes

We can see, then, the irony of the Roman soldier at the cross declaring that Jesus, a convicted criminal, was the son of God – and hence at least equal to Caesar!

-So, in God’s eyes, Jesus was a noble martyr, not the terrible criminal society condemned him to be.

Hmm, the centurion at the cross has a double function. He is the witness to Jesus’ death. In another line this becomes clear: “Pilate was surprised to hear that he was already dead. Summoning the centurion, he asked him if Jesus had already died.”

Moreover he is the last part of the mocking the false King of the Jews theme: When the centurion standing there in front of Jesus saw how He had breathed His last, he said, “Truly this man was the Son of God!”, meaning he declared him dead as a Roman emperor becoming a Divi Filius, a favourite theme in Roman satire.

I am struck by the contrast between the four gospels’ accounts of the discovery of the empty tomb and the three gospels’ (four counting Paul’s) accounts of the risen Jesus. In all four cases the empty tomb story is recognizably the same thing given various embellishments additions and exaggerations. But the accounts of the risen Jesus in Emmaus, no, on the shore of the sea of Galilee, no, on a hill in Galilee, no, in a locked room in Jerusalem, no, in front of an audience of five hundred people…. these are all just plain unrelated. I conclude from this that there was at a very early time an empty tomb story. But when that story became at a somewhat later time a resurrection story serving to preface Jesus’ appearances those appearances were constructed entirely differently by different groups. If there is an historical kernel to this set of affairs, it is the empty tomb story.

And I find it particularly interesting that the empty tomb story makes perfectly good sense from a completely secular perspective. A man is crucified and dies much earlier than anticipated. Rather than leave a corpse hanging on a tree (cf. Deut. 21:23) over the period of the Passover Sabbath a wealthy man, Joseph of Arimathea arranges to have the corpse placed in an expensive stone tomb that he has had constructed for his own purposes. The Sabbath concludes around 7 PM on Saturday. What happens next? Joseph has his servants remove the corpse to a place appropriate for its interment. Twelve hours or so after the Sabbath is over, women affiliated with Jesus come to the tomb and the corpse is not there. Perhaps a young man said something to them to the effect: If you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth he is not here.

Subsequently various stories began to be told about a risen Jesus appearing to his associates. But in the appearance of a gardener, or a mystery man on the road to Emmaus, as a spectacle to over five hundred men at one time, and so forth. And what, pray tell, are we to make of an account of over five hundred men apprehending the risen Christ at once (1 Cor. 15:6)? Paul believes that this happened prior to any appearance to James and that many eyewitnesses remain alive who can tell about it although some have died. The reference to their passing, as with the reference to James, indicates that Paul places this event pretty far back in time. I find this business very puzzling indeed. It seems to be testimony to the fact that there was a much greater size “Christian” movement at a very very early time than we generally think there was.