Recently, I was researching and preparing for the fourth chapter of the most recent Memory Mavens post. I wanted especially to resurrect, and then dismiss, Albert Schweitzer’s characterization of William Wrede’s work as “thoroughgoing scepticism.” I had already touched on this subject back in 2012 in our series on the Messianic Secret.

At the time, I quoted Wrede himself in his defense of reasonable skepticism.

To bring a pinch of vigilance and scepticism to [the study of Mark’s Gospel] is not to indulge a prejudice but to follow a clear hint from the Gospel itself.

In order to explain and defend Wrede’s method it seemed reasonable to me to compare it to Schweitzer’s (as Schweitzer himself had done, over 100 years ago). But then a funny thing happened. Try as I might, I could not find a single reference to “thoroughgoing scepticism” in the 2001 Fortress Press edition of The Quest of the Historical Jesus.

One of our shibboleths is missing

That seemed more than a little odd. Here is a catchphrase, set in stone within the hushed and hallowed halls of NT scholarship, and yet it was missing in action. Where had it gone? When did it leave?

The paper portion of my library, almost all of it, is miles away from me in a storage facility, so I’ve had to rely on electronic versions of Geschichte der leben-Jesu-forschung. The 1913 edition stored at Hathi Trust is in the public domain, and you should be able to read it, no matter what your country of origin is. (Sometimes Hathi Trust limits viewing to IP addresses from the U.S., because of unsettled copyright issues.)

As you probably already know, the first edition, in German, hit the streets in 1906, and it made a fairly big splash. NT scholarship in the English-speaking world took an immediate interest, which only grew when an English translation became available in 1910. Wrede’s The Messianic Secret would have to wait 60 more years. K. L. Schmidt’s Der Rahmen der Geschichte Jesu is still waiting.

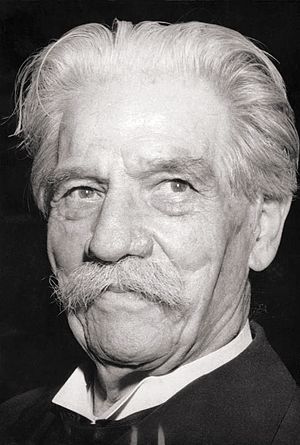

In the first edition, Schweitzer pokes Wrede in the eye with the title of chapter 19: “Thoroughgoing Scepticism and Thoroughgoing Eschatology.” Anglo-American scholars were delighted to see Wrede’s troubling thesis dispatched by such a towering, highly respected, intellectual figure. Who could ask for more?

Digging for nuggets, but not too deeply

Of course, Schweitzer’s magnum opus is, other than the Bible itself, the ultimate quote mine for English-speaking biblical scholarship. Certainly, no other modern work is so frequently quoted yet so rarely read. The Quest quickly became an indispensable quarry for scholars who are far too busy to read Reimarus, Strauss, Renan, or Wrede. Half-hearted, indifferent, indolent excavators have continued even into the late 20th and early 21st century, as this simple Google Books search demonstrates.

Consider the following examples:

James D. G. Dunn

In the same connection we should note also a point made by Schweitzer in his own response to Wrede. He climaxes his account of the quest with the contributions by Wrede and himself, as a choice between ‘thoroughgoing scepticism‘ (Wrede) and ‘thoroughgoing eschatology’ (Schweitzer). (Dunn 2003, Jesus Remembered, Christianity in the Making, p. 51)

C. K. Barrett

Schweitzer claimed that Wrede’s “thoroughgoing scepticism” had equally with his own “thoroughgoing eschatology” put an end to the quest of the historical Jesus. In at least one sense it could be said the Wrede had done this even more effectively than Schweitzer who had argued that the historical Jesus was completely unattainable since the bridges that might appear to connect us with him never reached the other side of the river but simply pointed into space — into theological thin air. Wrede indeed was not consistent, for he believed he had found a non-messianic historical Jesus, but in the process he had denied the validity of all evidence. (Barrett 1995, “Albert Schweitzer and the New Testament” Jesus and the Word: And Other Essays, p. 72)

Barret’s essay is actually a lecture from 1975, but I had to include it here because of the hilarious, weapons-grade nonsense he offers.

N. T. Wright

Albert Schweitzer bequeathed two stark alternatives to posterity: the “thoroughgoing skepticism” [sic] of William Wrede, and his own “thoroughgoing eschatology.” As we turn to the current scene in Jesus-studies, we discover that these two streets have become broad highways with a good deal of traffic all trying to use them at once. (Wright 2002, The Contemporary Quest for Jesus, p. 23, emphasis mine)

Wright here echoes Norman Perrin who, I believe, was the first to call Wrede’s line of thinking Wredestraße. See “The Wredestrasse Becomes the Hauptstrasse: Reflections on the Reprinting of the Dodd Festschrift: A Review Article.”

Ma’afu Palu

Schweitzer’s eschatological insight emerged in response to the many and varied attempts of nineteenth-century German theologians to write a Life of Jesus. These attempts, extensively documented by Schweitzer, conclude with the thoroughgoing scepticism of Wilhelm [sic] Wrede, who asserts that we can virtually know nothing of the historical Jesus. (Ma’afu Palu 2012, Jesus and Time: An Interpretation of Mark 1.15, p. 14, emphasis mine)

Palu and his editors missed the fact that Wrede’s first name was William. However, his research assistant got it right in the index, which is nice. However, I will offer kudos to Palu for correctly noting that some (e.g., Oscar Cullmann) have insisted that Schweitzer’s word, konsequente, should never have been translated as “thoroughgoing,” but rather as “consistent.” That makes a lot more sense in English.

Charles W. Hedrick

The earlier of these two books was published in 1901 by Wilhelm [sic] Wrede: The Messianic Secret (Das Messiasgeheimnis in den Evangelien. “The Messianic Secret in the Gospels”). Wrede’s book was the last study that Schweitzer considered in his own book. Wrede argued that the attempts of Jesus to silence disciples and demons, who knew his true identity as Son of God, was actually Mark’s literary creation to accommodate the fact (according to Wrede) that Jesus was not recognized as divine until after the church had come to believe in his resurrection. Hence, the “messianic secret” was not a secret initiated by Jesus, but rather it was a literary fiction invented by Mark. Schweitzer, however, disagreed with Wrede and affirmed the gospels as “historical” reports that could be used to write a historical description of Jesus. Schweitzer’s own description of Jesus comes at the end of his book in a chapter entitled “Thoroughgoing Scepticism and Thoroughgoing Eschatology.” Schweitzer asserts Jesus to be an eschatological prophet who expected the end of the world in his own lifetime. (Hedrick 2013, When History and Faith Collide: Studying Jesus, p. 17)

As is disturbingly common, Hedrick also misspells Wrede’s first name. I can’t explain why so many authors, proofreaders, publishers, and reviewers keep getting it wrong. He’s also mistaken about the secret being Mark’s invention.

I know it must sound as if I’m beating a dead horse here, but imagine if a biologist from our time wrote a book that claimed: “Karl Darwin’s theory of evolution explains abiogenesis.” No. Just no. It would never see the light of day, because people in the sciences cannot remain that ignorant of the facts and stay employed.

Gone, but obviously not forgotten

Getting back to Schweitzer, it turns out that by the second edition, he removed all references to “thoroughgoing scepticism.” He renamed Chapter 19: “The Criticism of the Modern Historical View by Wrede and Thoroughgoing Eschatology.” (In German, that’s: “Die Kritik der modern-historischen Anschaung durch Wrede und die konsequente Eschatologie.”)

He gave the book a thoroughgoing scrubbing, erasing it throughout the text. For example:

First edition (1906)

Thoroughgoing scepticism and thoroughgoing eschatology may, in their union, either destroy, or be destroyed by modern historical theology; but they cannot combine with it and enable it to advance, any more than they can be advanced by it. (p. 329, 1910 translation (Black))

Second edition (1913)

Wrede’s view and thoroughgoing eschatology can, in their union, either destroy or be destroyed by modern historical theology; but they cannot combine with it and enable it to advance, any more than they can be enriched by it. (p. 297, 2001 translation (Fortress Press))

Why did he go to all that trouble? The key lies in chapter 19’s first footnote (relegated to an endnote in the Fortress edition).

William Wrede was born in 1859 at Bücken in Hanover and was Professor at Breslau. When he succumbed to a heart attack in 1907 theology lost a noble man and a critical scholar, the importance of whom it recognized only by resisting him. In an article ‘On the Task and Method of So-Called New Testament Theology’ 1897, 80pp. (English translation edited by Robert Morgan in The Nature of New Testament Theology, London 1973, pp. 00-00), Wrede grapples with Holtzmann’s great work. As his predecessors in the criticism of the Gospel tradition Wrede mentions Bruno Bauer, Volkmar, and the Dutch writer Hoekstra, ‘De Christologie van het canonieke Marcus-Evangelie, vergeleken met die van de beide andere synoptische Evangelien’, Theologische Tijdschrift V, 1871. (Schweitzer 2001, p. 520, emphasis mine)

[Note: The pp. 00-00 citation above must be a placeholder. The actual pages are pp. 66-116.]

I would argue Schweitzer expunged the term “thoroughgoing scepticism” because he knew it was wrong. He realized he had incorrectly judged Wrede’s genius as well as his long-term influence.

He took out every single reference. From then on — from the second edition (1913) through the sixth edition (1950) — it was gone. In the 112 years since its publication, the term “thoroughgoing scepticism” existed in The Quest of the Historical Jesus only for the first seven.

An over-the-top insult

Don’t misunderstand me. He still strongly disagreed with Wrede’s conclusions. But Schweitzer did, I think, realize that Wrede was attempting to practice rational, consistent, historical critical analysis, and to call it “thoroughgoing scepticism” was an unsupportable insult.

Unfortunately, nobody in NT scholarship seems to have gotten the word. Fortress Press expended a great deal of effort, trying to give us an up-to-date English version of The Quest. But it would appear that no one is reading it. To be honest, I myself didn’t realize until this week that it was missing in the later editions. What interested me most about the Fortress Press edition were the added chapters.

Anyhow, if you catch someone talking about Wrede and saying he practiced “thoroughgoing scepticism,” consider reminding him or her that Schweitzer realized he was wrong and gave up that catchphrase over a century ago. Don’t stay mired in the past! Oh, and stop calling him Wilhelm!

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Neat work Neil.

And now for something vaguely similar….

From F.F. Bruce “The Epistle of Paul to the Romans” Tynedale New Testament Commentaries London First Edition 1963

On Page 25 Bruce discusses the various recensions of “Romans” noting that some texts omit the phrase “in Rome’ from Rom. 1.7., similarly at 1.15. [and more] .

But on p.30 he notes “But no other place-name could stand in the place of “Rome’ at Romans 1.7,15 because the context [Rom.1.8-15] refers to Rome and Rome only”.

Here is Rom.1. 8-15.

[8]First, I thank my God through Jesus Christ for all of you, because your faith is proclaimed in all the world.

[9] For God is my witness, whom I serve with my spirit in the gospel of his Son, that without ceasing I mention you always in my prayers,

[10] asking that somehow by God’s will I may now at last succeed in coming to you.

[11] For I long to see you, that I may impart to you some spiritual gift to strengthen you,

[12] that is, that we may be mutually encouraged by each other’s faith, both yours and mine.

[13] I want you to know, brethren, that I have often intended to come to you (but thus far have been prevented), in order that I may reap some harvest among you as well as among the rest of the Gentiles.

[14] I am under obligation both to Greeks and to barbarians, both to the wise and to the foolish:

[15] so I am eager to preach the gospel to you also who are : [in Rome].

So looking at this some years ago I could not see any context that absolutely required “Rome”.

So I asked the mob at the old BC and H site what, if anything I was missing.

Discussion ensued.

What I find interesting, and relevant to the Wrede/Schweitzer thingy, is that one person at BC&H said that his copy of Bruce’s work did not include the p. 30 comment.

If so, maybe Bruce changed his mind?

And perhaps “Romans” is misnamed?

Oh, and look, he’s writing to his brothers.

Oops sorry, neat work …Tim.