These posts for most part are following the argument of Wright, Elliott and Flesher in “Israel In and Out of Egypt”, a chapter in The Old Testament in Archaeology and History (2017), edited by Jennie Ebelilng, J. Edward Wright, Mark Elliott and Paul V.M. Flesher.

These posts for most part are following the argument of Wright, Elliott and Flesher in “Israel In and Out of Egypt”, a chapter in The Old Testament in Archaeology and History (2017), edited by Jennie Ebelilng, J. Edward Wright, Mark Elliott and Paul V.M. Flesher.

For Part 1 — see Exodus, part 1. Semites in Egypt

In Part 2 we look at the state of Egypt between the fifteenth and thirteenth centuries BCE.

Canaanites enter Egypt

In the previous post we saw that it was Egyptian weakness that allowed Asiatics to enter Egypt, often as unwelcome guests. In the Late Bronze Age, however, it was Egyptian strength that brought Canaanites into their homes.

Egypt was at the height of its power in the fifteenth century, especially under pharaohs Thutmose III and Amenhotep II of the eighteenth dynasty.

Thutmose regularly raided Canaan eventually to establish Egypt’s undisputed hegemony there. The crucial battle was at Megiddo in 1482 BCE.

One of the Canaanite place-names Thutmose had inscribed was Jacob-El. So the biblical narrative is not totally alien to this era.

Canaanites during this era of Egyptian domination became commonplace in Egypt. Canaanites brought tribute to Egypt; many were taken as hostages, especially as children, to be reared in Egyptian values before returning as loyal subjects to their original home cities.

Amenhotep boasted of transporting 89,000 people from Canaan to Egypt.

Perhaps there is an archaeological correlation; the population in the hill country in Canaan was drastically reduced during this period. Amenhotep III (1390-1353 BCE) records that his temple was filled with “male and female slaves, children of the chiefs of foreign lands of the captivity of His Majesty.” (Wright, p. 251)

Pharaoh Akhenaten

Many of us know the story of Amenhotep IV (1353-1336 BCE). He changed his name to Akhenaten in honour of his new god, Aten, the sun-disc. Many consider him the first monotheist. He was certainly a monolatrist, exalting his one god above all others as the only one truly worthy of worship and sole creator of the universe. He removed himself from the old capital dominated as it was by priests and temples for the old order and its chief god, Amen, and established a new city as the capital with new forms of art and architecture, and a new religion. Inscriptions and images of the old god, Amen, were erased from public monuments, temples and tombs throughout Egypt.

With his death his religious reforms also died and soon his own monuments to Aten suffered the same fate as he had inflicted on Amen. The old religion and its priesthood was restored.

Did Akhenaten’s religion influence the Israelites?

Even though Akhenaten’s monotheistic changes took place less than a century before an Israelite exodus could have happened, there is no indication that their religion was influenced by his activities. (Wright, p. 252)

Canaanites call on Egypt for help

Egypt had less of a presence in Canaan soon prior to and throughout the time of the Akhenaten “revolution”. Letters (part of what is known as the El-Amarna collection) from Canaanite rulers begging for Egypt’s help have been preserved and the tone of those letter indicates that Egypt was ignoring their pleas. Among the troubles that the Canaanite rulers were complaining about were threats from Apiru or Habiru. It was once tempting for scholars to associate Habiru with Hebrews but that view is no longer tenable:

The vassals’ letters frequently reflect local turmoil. Canaanite rulers engage in constant rivalries — plundering and fighting with one another and often accusing each other of treachery and disloyalty to the pharaoh. The letters also complain about the lack of Egyptian support in confronting marauding bands who live outside the cities that threatened Canaanite city-states and Egyptian authority. These groups are referred to as apiru or habiru and are known in Near Eastern texts throughout the second millennium BCE from the Euphrates to the Nile. The term has a derogatory undertone referring to a social class on the fringes of society, frequently identified as mercenaries, slaves, or outlaws. In some letters, Canaanite princes accuse their rivals of joining with the Apiru (even hiring them to attack the loyal supporters of the pharaoh) or claim that the rulers themselves are becoming Apiru (Grabbe 2007, 48). The letters frequently request Egyptian military support to rout these bandits—apparently these pleas were ignored by the Egyptians; the Canaanites were on their own.

When these texts were first discovered, many scholars attempted to link Apiru/Habiru with the Hebrews. However, today few scholars argue for a linguistic connection. Rainey argued that the terms are not related. “There is absolutely nothing to suggest an equation to the biblical Hebrews!” (Rainey and Schniedewind 2014, 33). The Amarna letters represent our most authentic view of Canaan in the fourteenth century BCE. Although many of the letters provide much information about Canaan in the Late Bronze age, no mention of any biblical event or character appears in them. (Ebeling, pp. 252f, bolding in all quotations is mine)

Egypt’s Ramessides and “Seth’s Man” Respond

The Egyptian dynasty following the turmoil of Akhenatens reign was the Nineteenth, also known after its founder, the briefly reigning Ramesses I, as the Ramessides. Ramesses successor, Seti I (Seti meaning “Seth’s man” — Aharoni 1967, 179) associated himself closely with the Semitic god Seth, a god widely worshiped in the delta region where many Semitic people’s had settled. Seti I launched a massive building program throughout Egypt and led his army into Canaan and Syria.

One of the peoples Seti fought against was the Shasu in the Sinai. Remember that name. We will return to it and note it has some significance to Yahweh worship.

Another one of the many peoples Seti claimed on temple wall reliefs to have overcome appears to have a close resemblance to the Israelite tribe of Asher. (This possible identification is not in the book edited by Ebeling et al that I am following here. Implicit in the argument, however, is also the possibility that later narratives drew upon distant historical memories of various groups who had once been known to occupy the Palestinian landscape.)

Seti recorded a victory over Apiru/Habiru from Mount Yarmath/Yarmuta.

Did the Exodus happen as late as 1250 BCE?

So far Egyptian history provides no indications of the Exodus event. Several scholars have suggested that if it happened at all then around 1250 BCE is a likely date. That is the time of Rameses II.

Rameses II has the advantage of being a great builder and we look for matches between his building programs and Exodus 1:11

So they put slave masters over them to oppress them with forced labor, and they built Pithom and Rameses as store cities for Pharaoh. (NIV)

Rameses II did build in the delta region where we know many Semites had settled:

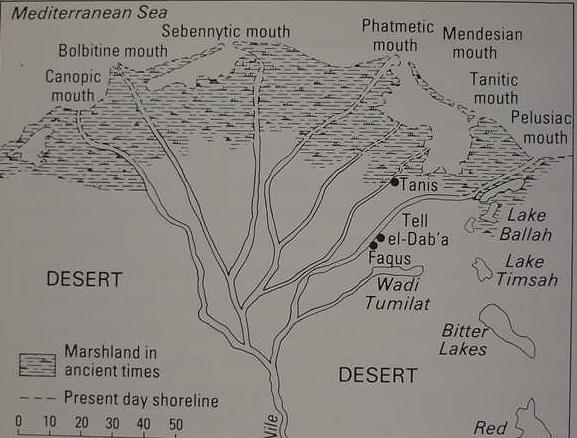

Ramesses expanded the city of Avaris, now called Pi-Rameses, and made the delta city his principal residence. Because of its strategic location, it soon became an influential economic center and an Egyptian military installation. The delta has always been a home to Semitic influences, and “many foreign deities such as Ba’al, Reshep, Hauron, Anat, and Astarte… were worshipped in Plramesse” (Van Dijk 2000, 300). In addition to the evidence of Apiru laboring at Pi-Rameses, his bureaucracy and the army contained a number of foreigners. (Ebeling, pp. 254f.)

The city of Rameses in Exodus 1:11 is not a serious problem:

Most scholars agree that Rameses (Pi-Rameses, lit. “house of Rameses”) should be located at Qantir, just northeast of Tell el-Daba . . . (Ebeling, p. 255)

Or was the story invented in the 600s BCE?

Prominent scholars such as Donald Redford (Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times), Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman (The Bible Unearthed) have argued that

the story is a seventh-century B.C. creation by writers living and working during the time of Josiah in Judah and/or the 26th (Saite) Dynasty in Egypt. (Cline, From Eden to Exile)

Pithom (Ex 1:11) is the problem.

[T]here is no agreement on the location of Pithom (Egyptian Pi-Atum, lit. “House of Atum”). Divided opinion identifies Pithom with the sites of Tell er-Retaba or Tell el-Maskhuta. The site of Tell er-Retaba may date to the thirteenth or twelfth century BCE. Its occupation ends in the seventh century BCE as Maskhuta was being built. Maskhuta is problematic. Although it contains building material from the period of Ramesses II and statuary inscribed “Pithom,” it was constructed in the seventh century BCE (Finkelstein and Silberman 2001,63). The blocks, steles, and statues uncovered at Maskhuta must have come from er-Retaba. It is the only major site “that could have produced such material” for building the late seventh-century BCE Maskhuta (Hoffmeier 2005,61). If the author of the book of Exodus believed the Israelites built Pithom at Tell el-Maskhuta, then the story is clearly a seventh-century BCE invention. (Ebeling, p. 255)

Part 3 to follow.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

You might also see my extensive discussion of the date of the geographical references in the Exodus story in Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus (2006), Chapter 10, “The Route of the Exodus.”

Yes, I agree that the evidence points to the story appearing no earlier than the third century BCE. The reason I have not presented that option so far is because I am wanting to present what is found in the latest relatively comprehensive publication on the Bible and archaeology. I am still working on other posts on your Plato book, too, by the way.

It’s an interesting series of posts about the Exodus. Well researched and presented as always.

Thanks, Russell. We should have known that Neil has not forgotten your work.

Does the chapter you are commenting on provide any references to support the contention that “One of the Canaanite place-names Thutmose had inscribed was Jacob-El. So the biblical narrative is not totally alien to this era.”

I was relying on the following from page 251 in Ebeling:

Aharoni 1967 = Aharoni, Yohanan. 1967. The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography. Translated by A. Rainey. Philadelphia: Westminster.

There is a discussion of Jacob-El at the Institute for Biblical Archaeology & Scientific Studies site.