The survey of Muslim religiosity was carried out in

- Indonesia,

- Pakistan,

- Malaysia,

- Iran,

- Kazakhstan,

- Egypt

- and Turkey.

It included statements on the respondents’ image of Islam. The survey listed forty-four items that examined religious beliefs, ideas and convictions. These statements were generated by consulting some key sociological texts on Muslim societies by authors such as Fazlur Rahman, Ernest Gellner, William Montgomery Watt, Mohammad Arkoun and Fatima Mernissi. Respondents were asked to give one of the following six responses to each of the statements presented: strongly agree, agree, not sure, disagree, strongly disagree, or no answer. More than 6300 respondents were interviewed. (Hassan, Inside Muslim Minds, p. 48)

This is post #5 on Inside Muslim Minds by Riaz Hassan. We are seeking an understanding of the world. If you have nothing to learn about the Islamic world please don’t bother reading these posts since they will likely stir your hostility and tempt you into making unproductive comments.

We have looked at a historical interpretation of how much of the Muslim world became desensitized to cruel punishments and oppression of women and others. But what does the empirical evidence tell us? Here Hassan turns to a study explained in the side-box. Each question was subject to a score between 1 and 5, with “very strong” being indicated by 1 or 2.

Following are the 20 questions (out of a total of 44) that generated the highest mean scores.

Overall the results tell us that Muslims feel strongly about “the sanctity and inviolability” of their sacred texts. There is a strong belief overall that all that is required for a utopian society is a more sincere commitment to truths in those texts.

In other words, there is a large-scale rejection of modern understandings of the genetic and environmental influences upon human nature.

The evidence indicates very strong support for implementing ‘Islamic law’ in Muslim countries. (On “Islamic Law” see Most Muslims Support Sharia: Should We Panic?) Respondents strongly support strict enforcement of Islamic hudood laws pertaining to apostasy, theft and usury. The purpose of human freedom is seen not as a means of personal fulfilment and growth, but as a way of meeting obligations and duties laid down in the sacred texts. This makes such modern developments as democracy and personal liberty contrary to Islamic teachings. The strong support for strict enforcement of apostasy laws makes any rational and critical appraisals of Islamic texts and traditions unacceptable and subject to the hudd punishment of death. The strength of these attitudes could explain why hudood and blasphemy laws are supported, or at least tolerated, by a significant majority of Muslims. Strong support for modelling an ideal Muslim society along the lines of the society founded by the Prophet Muhammad and the first four Caliphs is consistent with the salafi views and teachings discussed earlier. (p. 54)

But notice:

Once again, such views are stronger in some Muslim countries than in others.

The view expressed so strongly that a true Islamic identity can only be found through a strict adherence to certain Islamic beliefs and duties raises a host of problematic questions for Muslims living in predominantly non-Muslim societies, as well as in Muslim countries like Kazakhstan and Turkey. The reality is, on the contrary, that many Muslims find their identity in family, ethnicity and cultural heritage. Hence it is a mistake to speak of Islam as some sort of ideologically monolithic beast and to accuse “moderate Muslims” of simply being “insincere” or “not truly faithful” in their religion.

This belief does not provide any political and cultural space for the coexistence of multiple routes through which Muslim identities are constructed in modern societies. (p. 55)

Notice the areas where there was a Disagreement in certain Islamic nations, especially #15 and #19 where patriarchal traditions are addressed. Iran, Kazakhstan and Turkey do not equally share those patriarchal attitudes.

Other differences appear with these three nations, too. If we are looking for explanations it may be pertinent to notice that . . . .

Iran is dominated by diverse ethnic groups, especially Persian and Azari, has had a relatively higher degree of national prosperity than many other Muslim states, and is predominantly Shia, not Sunni, and in fact has been at war with Sunni Iraq.

An important characteristic of Shi’ahism is that it tends to be intellectually more oriented to ijtihad (innovation) than Sunni Islam is; hence, many scholars regard it as less tradition-bound than Sunni Islam. (p. 20)

Kazakhstan with its many years as part of the Soviet Union has also had a very different history from many other Muslim populations. And I think we are generally aware of the secular heritage of Turkey since Ottoman rule. (As for current developments in Turkey I find an earlier post here to have been prescient: Can Democracy Survive a Muslim Election Victory?)

The point is that even with Islam, just as we have learned to expect with any other religion, time and circumstance, historical experience and cultural heritage are central to shaping of its expression and interpretation.

1. The Qur’an and Sunnah contain all the essential religious and moral truths required by the whole human race from now until the end of time

| Egypt | Very strong (= mean score less than 1.95) |

| Indonesia | Very strong |

| Iran | Very strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong (= mean score between 1.96 and 2.95) |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

2. What is required is a deeper appreciation of the essential principles implicit in the Qur’an and Hadith, so that solutions to contemporary problems can be found

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Very strong |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

3. The Qur’an and Sunnah are completely self-sufficient to meet the needs of present and future societies

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Very strong |

| Iran | Very strong |

| Kazakhstan | Very strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

4. It is a duty of Muslims to strive to establish a truly Islamic society

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Very strong |

| Iran | Very strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

5. Freedom should not mean licence to do anything one chooses in the name of self-fulfilment

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Very strong |

| Iran | Very strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

6. Any state will be imperfect unless it is based on moral values implicit in the shari’ah and also on belief in Allah as the upholder of morality and justice

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Very strong |

| Iran | Very strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

7. Muslim society must be based on the Qur’an and shari’ah law [Again, on “shari’ah law” see Most Muslims Support Sharia: Should We Panic?]

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Very strong |

| Iran | Very strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Disagree (= score greater than 2.96) |

.

8. Women should observe Islamic dress codes

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Very strong |

| Iran | Very strong |

| Kazakhstan | Very strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

9. I believe society would be better off if it were run by people of explicit religious conviction, who are willing to act morally and politically on those convictions

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Very strong |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

10. Human nature is unchanging and this is the reason for Muslim scholars asserting the finality of rules and laws for human conduct that are expressed in the Qur’an and Sunnah of the Prophet

| Egypt | Strong |

| Indonesia | Strong |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

11. Authentic human fulfilment depends upon the existence of conditions in society by which it is possible to pursue divine will

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Strong |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

12. Islamic laws about apostasy should be strictly enforced in Muslim countries

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Strong |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Disagree |

.

13. The ideal Muslim society must be based on the model of early Muslim society under the Prophet and the Khulafa-e-Rashideen

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Strong |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Very strong |

.

14. Strict enforcement of punishment under Islamic law such as amputation of limbs for theft will significantly reduce crime

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Strong |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Disagree |

.

15. Women are sexually attractive, and segregation and veiling are necessary for male protection

| Egypt | Strong |

| Indonesia | Strong |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Disagree |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Disagree |

.

16. Charging of interest on loans by banks should be strictly prohibited in Muslim countries

| Egypt | Strong |

| Indonesia | Strong |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Disagree |

| Malaysia | Strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Disagree |

.

17. Islamic identity can be preserved only through faithful adherence to traditional Islamic beliefs and duties

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Disagree |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Strong |

| Malaysia | Very strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

18. Many fundamentalists are educated and sophisticated people who are genuinely concerned about the moral, social, political and economic failures of their respective societies and who believe that the answer lies in a return to religious values and lifestyles

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Strong |

| Iran | Strong |

| Kazakhstan | Disagree |

| Malaysia | Strong |

| Pakistan | Very strong |

| Turkey | Very strong |

.

19. If men are not in charge of women, women will lose sight of all human values and the family will disintegrate

| Egypt | Very strong |

| Indonesia | Strong |

| Iran | Disagree |

| Kazakhstan | (Not asked in Kazakhstan) |

| Malaysia | Strong |

| Pakistan | Strong |

| Turkey | Disagree |

.

20. It is not practical or realistic to base a complex modem society on the shariah law

| Egypt | Disagree |

| Indonesia | Disagree |

| Iran | Disagree |

| Kazakhstan | Disagree |

| Malaysia | Disagree |

| Pakistan | Disagree |

| Turkey | Strong |

.

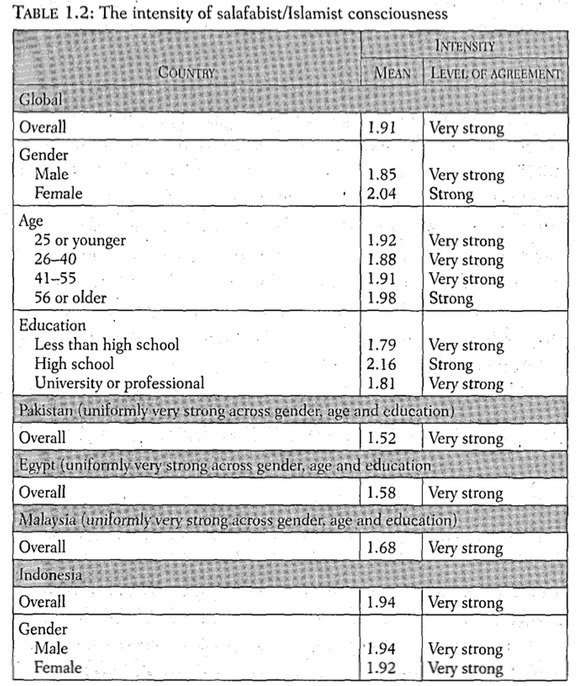

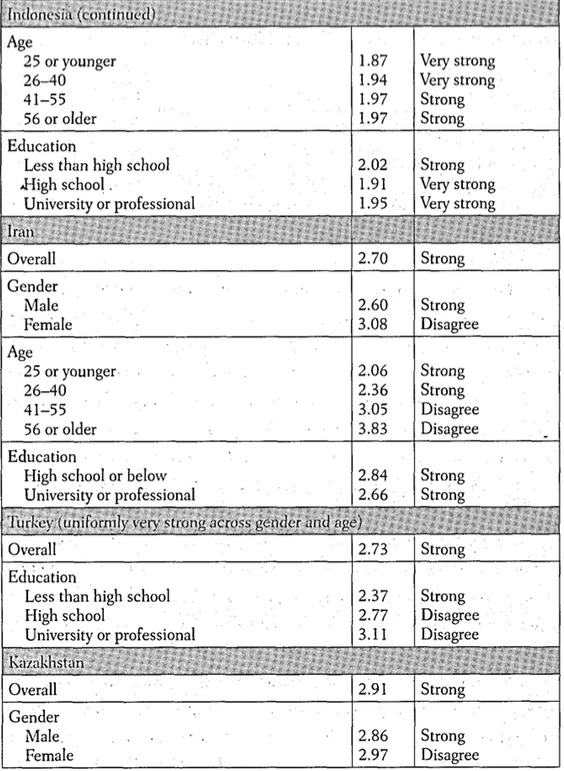

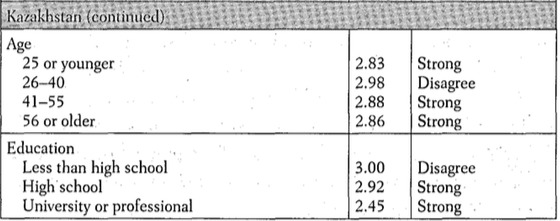

Riaz Hasan provides another table providing a more informative breakdown of how different age groups, genders and education levels responded to the sort of questions above. I have attempted to copy crude screen shots of it at the end of this post. (It ain’t easy getting things perfect here on a late evening in a Bali bar with some pretty wild live music . . . .) But here are some conclusions Hassan draws from the data:

The variations in intensity of salafabist/Islamist religious orientation are most likely the result of the different political, social and economic paths taken by the individual countries.

Kazakhstan was a communist, anti-religious country for much of the twentieth century.

Likewise, the secular political history of modern Turkey helps explain the not-so-strong salafabist/Islamist religious orientation of the Turkish respondents.

Iran is the only theocratic country among the countries studied; yet Iranian respondents display a relatively weak salafabist/Islamist orientation. One possible explanation is that Iran is a predominantly Shi’ah country and Shi’ahism tends to be more intellectual than its Sunni counterpart. Another reason might be that trust in religious institutions tends to decline in any nation when religion and politics are fused. (p. 59)

Then,

The salafabist consciousness was very strong among respondents in Malaysia, Pakistan and Egypt whatever their gender, age or educational attainment.

In other countries, these factors appeared to have some influence on the findings. In Indonesia, there was an inverse correlation with age. In Iran and Kazakhstan, there was an inverse correlation with gender as the female respondents in these countries rejected salafabism. In Turkey and Kazakhstan, the findings indicated a complex relationship with educational attainment. These diverse patterns of relationships between salafabism and sociodemographic factors are a product of social conditions unique to individual countries. (pp. 59-60)

Conclusion

Salafabist/Islamist discourse has gained considerable influence among Muslims today. The empirical evidence presented above [and at the end of this post] demonstrates an intense belief among many Muslims in the self-sufficiency of Islamic texts and an attitude towards them that is literalist, anti-rational and anti-interpretive. Religious texts are seen not as moral and religious guides, but as a secure refuge for an intellect that is unable to confront the challenges posed by modernity and is, by and large, hostile to them.

Such a mindset can be characterized as self-righteous, arrogant, supremacist and puritan. It compensates for the feeling of alienation and powerlessness arising from the general economic, social, political and technological backwardness of the Islamic world. It is further characterized by strong patriarchal and misogynist attitudes that deny Muslim women equality of citizenship, indicate an obsession with the sexual allure of women and pose important questions about the sexuality and insecurities of Muslim men.

This salafabist strand of modern Muslim consciousness can be seen as a product of the historical experience of Muslims over the past three centuries. Large-scale social and political factors have played an important role in shaping it and might also explain the variations in its intensity in different countries. Understanding it is essential to an understanding of the cases described at the beginning of this chapter. As the events of 9/11 and its aftermath have demonstrated, the followers of salafabism are capable of meticulously carrying out extreme acts of destructiveness.But can salafabism produce the type of world that will provide economic and social justice for Muslims? The mentality underlying the logic that produced 9/11 and the acts described at the beginning of this chapter represent at best a reckless and ruthless effort to repair Muslim identity; indeed, this mentality offers no thoughts about how to construct the type of world that most Muslims would like to see for themselves and future generations. Will today’s Muslims be able to take up the challenge of marginalizing salafabism, or will they be overwhelmed by it and, in the process, be marginalized themselves? This is probably the most pressing challenge facing Muslim intellectuals today. (pp. 60-61)

And all of that is just chapter 1 of Riaz Hassan’s Inside Muslim Minds. Subsequent chapters get down to the nitty gritty of attitudes towards the specifics. I can post more on those later. Meanwhile I have other newer reading to catch up on and write about.

I trust that these five posts will put to rest any notion that my posts discussing the research into the causes of terrorism and radicalization are attempts to whitewash “Islam”. Islam does not need, indeed it cannot be, “whitewashed”. Probably no human product can ever be “whitewashed”. At the same time “demonizing” Islam, like demonizing any human endeavour or group, gets us no further morally than when we demonized the Jews, the Catholics, the blacks, the homosexuals, anyone fitting the template of a witch . . . . What matters is informed understanding, surely.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“It is a duty of Muslims to strive to establish a truly Islamic society.”

Every country responded with: “strong” or “very strong”.

We don’t want to live in a truly Islamic society.

Islam is incompatible with Western values of separation of religion and state.

Sigh! There is no such “thing” as “Islam” any more than there is such a “thing” as Christianity or Judaism. Religion is not a force that controls people like a demonic power. That’s not how religions work and certainly not how any people work.

I am still dismayed that “all Muslims” or “Islam itself” is seen as a monolithic evil just like we have viewed the Jews and blacks etc that same way. None so blind as they who will not see. My essays were not meant for you. You have nothing to gain from them.

I have also posted on a collection of essays put together in Muslim Secular Democracy by Rahim.

I define “Islam” as what the Quran mandates. And it mandates world conquest by any means necessary.

Of course, not all Muslims faithfully follow the dictates of the Quran. But this does not mean, as you said, that “there is no such thing as Islam”. Yes. We can say, “there are many Islams”. But pretty much all of them suck to one degree or another. And a significant percentage of Muslims are dedicated to replacing our secular way of life with their religion. This is not acceptable.

Books don’t speak for themselves. They are always interpreted. And your interpretation of what the Quran mandates in fact contradicts other passages that it also “mandates”. There is no such entity as “Islam” any more than there is a single entity as “Judaism” or “Christianity”.

You don’t think it a mark of arrogance for an outsider to dictate to others what their religion is?

“Books don’t speak for themselves.”

Please refrain from straw man arguments.

“You don’t think it a mark of arrogance for an outsider to dictate to others what their religion is?”

Unless you are a Moslem, you are an outsider who deigns to know what Islam is.

There is no straw man argument. That books do not speak for themselves is a simple truism among all reasonably literate persons. It is stock in trade of all literary analysis.

But your tone is hostile and your last line is also indicative of a closed minded bigotry incapable of discussing this topic objectively.

Bad man. Moderation list for you.

I am just passing through this place. I was actually looking for critical responses to Maurice Casey’s book ‘Jesus of Nazareth’. I am actually a busy UK schoolteacher who has to fit their private reading around what is, on average, a 60 hour week. So everything has to be done on the hoof, including this post. However, I do try to keep up with reputable scholarship on Islam and I reckon that you may need to broaden the scope of your reading a little (as we all do).

For starters, another survey of global Muslim attitudes is M. Steven Fish’s ‘Are Muslims Distinctive? A Look at the Evidence’. I haven’t read Hassan so am unable to compare the two publications but Fish is better known and his research has been well-received.

Shiraz Maher’s ‘Salafi-Jihadism’ and Tarek Osman’s ‘Islamism’ are two recent publications that may deepen your understanding of those two phenomena.

I would also very strongly recommend Shahab Ahmed’s magisterial and groundbreaking study ‘What is Islam? The importance of being Islamic.’ Until anyone has dipped into this, they should be wary of drawing any far-reaching conclusions about the faith, as ‘Jon’ seems to his final sentence above.

With that sentence in mind, Asma Afsaruddin’s ‘Contemporary Issues in Islam’ is a book which explores the vexed issue of the alleged incompatibility of Islam with democracy, along with several other controversial topics (sharia, jihad, the caliphate, the status of women, and interfaith relations). It’s a quick but enlightening read. Then there’s Abdulaziz Sachedina’s ‘The Islamic Roots of Democratic Pluralism’.

Lastly, for a bit of contrast, it can also be worth keeping an eye on the taqwacore movement, especially the writings of Michael Muhammad Knight (a sort of Hunter S. Thompson of Islamic literature) and the music of the wonderful band, the Kominas. Start with this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K6T3Mh9cu8s

You can find our posts on Casey’s Jesus of Nazareth @ http://vridar.org/category/book-reviews-notes/casey-jesus-of-nazareth/

Hassan’s particular research makes an important contribution to an empirically based understanding of modern Islam. Perhaps you fear that these posts lack balance or such? I have chosen to focus on his first chapter to present a combination of historical and empirical explanation for the tolerance of the intolerance in societies like Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, — and to explain why among our fellow creatures there appears to be such strong support for some very narrow-minded belief systems and oppressive behaviours. Scholarly review in JSTOR gives a more complete picture of what Hassan’s argument is overall.

I have posted on the other side of “Islam” as well as Islamism, terrorism, radicalisation processes, etc. so often and wanted for a change to demonstrate that I have indeed read studies into the disturbingly widespread negative side of the Islamic world and do not try to “whitewash” anything.

What I want to follow up with later is some of the subsequent findings of Hassan regarding Islam and democracy, jihad, women, etc etc etc ….. in the context of this series of 5 posts.

If you are concerned that I have left a distorted or seriously under-informed presentation in these 5 posts then please do give me something specific to address.

Among monographs (not including a couple of hundred of mostly peer-reviewed articles, reports, presentations, Islamist and terrorist tracts, etc) I have used as sources for other posts on Islam, Islamism, terrorism, radicalization etc. . . .

(machine generated bibliography — excuse some glitches)

If any of your recommendations add significantly to the above do please advise!

What is the credibility status of Hassan’s “Inside Muslim Minds”? There are internet reviews but I quote below extracts from a JSTOR review that is not freely open access: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41722810 (my own bolding):

And so forth. I trust interested readers will see the value in past and future posts drawn from Riaz Hassan’s work.

Neil, from my very brief acquaintance with your site, I think it is highly impressive. I have acquired or am intending to wade through several of the titles you cite above (Atran, Cockburn, Pantucci, McCants, Cook). Though you are way ahead of me, we seem to be following a similar trajectory, so that’s why I thought that I might mention a few additional works that are helping to shape my own outlook.

I do think you may also find the Shiraz Maher and Tarek Osman books to be useful additions to those you already cite. But the real one to go for is the Ahmad. Malise Ruthven has recently written an interesting review of this work for, I think, the London Review of Books. It is apparently causing quite a stir in academic circles and is finding its way onto university reading lists over here in the UK.

My problem is that I am kept very busy by the ordinary routines of school administration (I have just set aside some marking to type this brief response). So I won’t have time to maintain any kind of ongoing dialogue with you. But I will pop back in a couple of weeks or so when there is a half-term break.

Thanks for the Casey link. I have taken the plunge and bought a copy to see what all the fuss is about. It’s been over 20 years since I last read something on the quest for the historical Jesus and my interest was piqued by Reza Aslan’s ‘Zealot’ which I have just started.

Best wishes!

The Ahmed book is available online, I see: https://archive.org/details/WhatIsIslamTheImportanceOfBeingIslamicShahabAhmed

Having lived in one or two of the Muslim countries you named, it was interesting to compare the actual behavior I observed there, with the written responses. I suspect there may be some differences. Much as there is in say, America. Where often people, trained to take texts, give the response they think will be the most acceptable or “right” answer. As in the Pew surveys.

So we all need to be aware of that possibility.

By the way: the title seems a bit abrupt. Wouldn’t it be more politic to use a slightly softer title? Often religious folks without academic experience don’t read past one or two excerpted titles. And they might be upset by this. Even with a lot of apparent scholarship and a Muslim scholar behind it.

Best wishes.

Scholarly researchers are very well aware of the pitfalls of survey data and that’s why anything worthwhile includes a detailed explanation of how it was conducted, the sample size and coverage, etc. I trust I have included enough information in these five posts to alert serious readers to this sort of information.

The title is deliberately abrupt because there really is a serious problem within the Islamic world right now. I have also spent time in three of the countries surveyed and am in Indonesia right now, in fact only a kilometer or so from a large memorial to over a hundred victims of a terrorist bombing a few years ago.

My posts over the years have tried to focus on an accurate and honest understanding of Islam, Islamism, terrorism, and the processes of radicalization. These latest five posts have attempted to extend that understanding to the undeniable public support for brutality and injustices in whole regions of Pakistan, etc. Not far from here — Solo — was a refuge for terrorist gangs but I understand the Indonesian military has cleared them out. I don’t know how completely, though. My visit to Solo was a mixed experience. The dominance of a far more conservative Islamic element there than in other places I have visited is palpable.

Neil, I have just found a bit of time to swing past here again. Like yourself, I have also been attempting to make sense of ‘Islam, Islamism, terrorism and the process of radicalization’. I get through about thirty books a year and usually about ten of them are to do with the above topics. This means that I’m in for the long haul, as I haven’t started some of the books I have already recommended to you yet (though the reason I did so is because a mate of mine who is undertaking a similar enterprise right now but has a lot more time available than I do has been enthusing about some of them, namely, Maher, Atran and Ahmed).

As far as understanding the process of radicalization is concerned, two books I have found to be very helpful are Arun Kundnani’s ‘The Muslims Are Coming!’ and Andrew Silke’s more general and brief survey, ‘Terrorism: All That Matters.’

On the Qur’an, Neal Robinson’s ‘Discovering the Qur’an’ is a work of utterly formidable scholarship, while Ziauddin Sardar’s ‘Reading the Qur’an’ is good for gaining an outline of liberal Muslim positions on topics like homosexuality, free speech, Sharia, the Veil, and so on.

For hadith, Jonathan A.C. Brown’s ‘Misquoting Muhammad’ is a good overview. I also liked his OUP very short introduction to the Life of Muhammad (though I like Maxime Rodinson’s warts and all portrayal even more).

Lastly, Mark LeVine’s ‘Heavy Metal Islam’ is a good source for taking the temperature of Muslim attitudes in several countries in the MENA. It’s not a formal piece of writing or some kind of ethnographic study but LeVine is also a musician who has got to know the alternative music scenes in countries like Egypt and Pakistan. Those scenes are inherently political and the views of the Muslims he talks to probably wouldn’t show up on Hassan or Fish’s barometer. I was sufficiently impressed to go out and purchase his ‘Why They Don’t Hate Us’ but I haven’t started it yet.

Hope this helps in some way.

I need to organize my own posts for easy reference but can list the following you may also find of some interest:

McCauley and Moskalenko’s Friction: How radicalization Happens to Them and Us

Jason Burke’s The New Threat

Unfreezing. Gateway to Radicalisation (Comparing Cults and Terrorist Groups Once More)

Does growing “dewy-eyed at the mere mention of Paradise” lead to suicidal terrorism?

Violent Islamism: Many are Called, Few are “Chosen”, Fewer Defect

Common Reasons for Joining ISIS and Fighting ISIS

The Founder of Islamist Extremism and Terrorism

How Religious Cults and Terrorist Groups Attract Members

Islamic Radicals and Christian Cults: Cut from the Same Cloth

Cults & Terrorists in Christianity and Islam

Who Joins Cults — and How and Why?

[comment deleted because I cannot see its relevance to the post. — Neil]

Bob — do you have any thoughts on the above post or on the series that is concluded in the above post?

Neil, your post is about “Inside Muslim Minds”. I find it very interesting. My Reply of yesterday added a snippet of thought of another ‘Muslim Mind”, of a prominent Muslim living in the west.

One conclusion you highlight here is “This makes such modern developments as democracy and personal liberty contrary to Islamic teachings.”

I happen to know that this Muslim (important politician in his country, sometimes mentioned as future prime-minister) holds a different view in these aspects (democracy, personal liberty, victim of Western imperialism), and thought it would be of interest to refer to a short interview with him on Saudi television. This nicely contrast the – official – Saudi opinions with the views of Muslims in non-Muslim countries.

I am rather disappointed you deleted the reference I gave in my Reply of yesterday; there is nothing offensive in it, and – in fact – it confirms much of what is said in your posts; just adds a view to it.

Sound bytes from controversial political figures pursuing their political agendas add nothing to the level of discussion and understanding I am seeking to promote here. His comments bear no relation whatever to the theme of this series, an nothing whatever to a global understanding of Muslim peoples.

For you to think this blog is comparable to a forum for shock-jock like proclamations calculated for a patently self-serving political effect only tells me you have completely failed to grasp the most basic theme and understanding this series has been seeking to promote from notes on Riaz Hassan’s chapter, that the difference between scholarly research and political declamations completely eludes you.

Aboutaleb is not in the least controversial. What do you actually know about him? The interview on Saudi television can not be seen as ‘pursuing a political agenda’: Aboutaleb is mayor of a city in Europe….

I’m sorry that you close your eyes for the views of prominent, and widely respected, Muslims

That’s enough, Bob. Your determination to avoid addressing the content of these posts and to latch on to nothing more than a single word in any of my comments, otherwise avoiding their point, is tiring. Your attempt to deny Aboutelab is known for controversial forthright speaking is disingenuous.

I have quoted many individual Muslims on this blog, even in this post!, but if you can’t see past the political-speak of politicians, words calculated for political ends, Muslim or otherwise, then you have no appreciation whatever of what constitutes the sort of discussion I am trying to promote here.

I happen to find myself in agreements with soundbytes of certain political leaders but would never think of quoting them as any sort of authority for any point I am trying to address in a certain way on the blog.

If you want to have a comment posted here again then address the post and not some politician who knows how to tug on the views of his target constituency.

I cannot believe you have bothered to even read these posts.

His name is Ahmed Aboutaleb (not “Aboutelab”).