Most objections to my posts on terrorism seem to fall back on arguing how frightening or horrific the religion of Islam is. Because I don’t “blame Islam” for terrorism (I distinguish between Islam and the political ideology of Islamism that originated with Maududi and Qutb) some readers assume I am trying to “whitewash Islam”. Not so. I have frequently tried to point out that I have no time for any religion personally and acknowledge that much of the Islamic world in particular has a long way to go in terms of meeting modern standards enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. At the same time I reject absolutely the view that the Islamic religion is some sort of monolithic demon that has the power to possess and dehumanize anyone who succumbs to the teachings of the Quran.

Before I studied terrorism I tried to learn a little about Muslims and Islam. Apart from reading the Quran and engaging with local Muslims I sought out a more comprehensive understanding of Islam globally from a range of sources. The ones I found the most useful are in bold type (though the others are worthwhile, too):

Before I studied terrorism I tried to learn a little about Muslims and Islam. Apart from reading the Quran and engaging with local Muslims I sought out a more comprehensive understanding of Islam globally from a range of sources. The ones I found the most useful are in bold type (though the others are worthwhile, too):

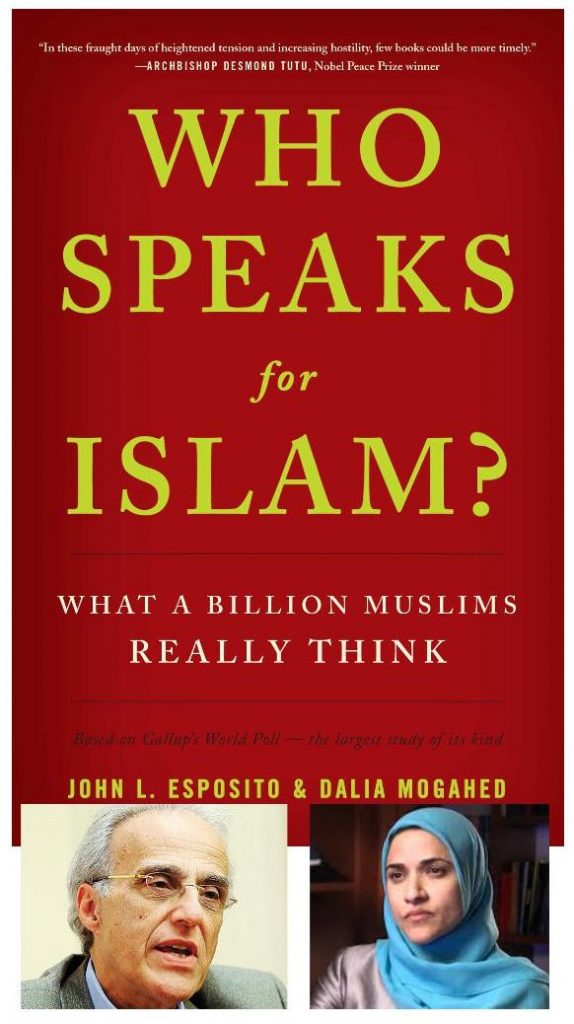

- Esposito, J. L. & Mogahed, D. (2007). Who speaks for Islam?: what a billion Muslims really think. New York, NY: Gallup Press.

- Harris, S. (2015). Islam and the future of tolerance: a dialogue. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Hassan, R. (2008). Inside Muslim minds. Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Press.

- Negus, G. (2004). The world from Islam: a journey of discovery through the Muslim heartland. Pymble, N.S.W.: HarperCollins.

- Rahim, L. Z. (2013). Muslim secular democracy: voices from within. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Saikal, A. (2003). Islam and the West: conflict or cooperation? New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

I want to post some of what I learned from the above. In this post I will limit myself to just one section from Esposito and Mogahed’s Who Speaks for Islam? This volume is the result of a Gallup research study between 2001 and 2007 interviewing tens of thousands of Muslims in hour-long, face-to-face interviews in more than 35 nations. The sample included young and old, educated and illiterate, female and male, urban and rural. The sample represented more than 90% of the world’s Muslims and at time of publication was “the largest, most comprehensive study of contemporary Muslims ever done”. Results are statistically valid within a +/- 3-point margin of error.

Should Majority Support for Sharia Make the West Panic?

We would be surprised if most Christians said they did not support the Sermon on the Mount and if most Jews claimed not to support the Ten Commandments. But Sharia?

Sharia has been equated with stoning of adulterers, chopping off limbs for theft, imprisonment or death in blasphemy and apostasy cases, and limits on the rights of women and minorities. The range of differing perceptions about Sharia surfaced in Iraq when Shia leaders, such as Iraq’s senior Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, called for an Islamic democracy, including Sharia as a basis of law in Iraq’s new constitution. (Esposito & Mogahed 2007, p. 49)

Then came the invasion of Iraq and the setting up of a committee to draft a new constitution. A Christian Iraqi member of that committee, Yonadam Kanna, warned that “making Sharia one of the main sources of law” would lead have dire consequences, especially for women.

Nevertheless, more than 1,000 Iraqi women rallied in support of Sharia in the southern city of Basra in August 2005 in response to another rally opposing Sharia in Baghdad a week earlier. (p. 50)

Many in the West confuse Sharia law with a theocracy or rule by religious clerics but the two are quite separate things. Citing Gallup Poll data Esposito and Mogahed explain:

Although in many quarters, Sharia has become the buzzword for religious rule, responses to the Gallup Poll indicate that wanting Sharia does not automatically translate into wanting theocracy. Significant majorities in many countries say religious leaders should play no direct role in drafting a country’s constitution, writing national legislation, drafting new laws, determining foreign policy and international relations, or deciding how women dress in public or what is televised or published in newspapers. Others who opt for a direct role tend to stipulate that religious leaders should only serve in an advisory capacity to government officials. (p. 50)

Women, equal rights and the data

In the West, Sharia often evokes an image of a restrictive society where women are oppressed and denied basic human rights. Indeed,women have suffered under government-imposed Sharia regulations in Muslim countries such as Pakistan, Sudan, the Taliban’s Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, and Iran. However, those who want Sharia often charge that these regulations are un-Islamic interpretations. Gallup Poll data show us that most respondents want women to have autonomy and equal rights. Majorities of respondents in most countries surveyed believe that women should have:

■ the same legal rights as men (85% in Iran; 90% range in Indonesia, Bangladesh, Turkey, and Lebanon; 77% in Pakistan; and 61% in Saudi Arabia). Surprisingly, Egypt (57%) and Jordan (57%), which are generally seen as more liberal, lag behind Iran, Indonesia, and other countries.

■ rights to vote: 80% in Indonesia, 89% in Iran, 67% in Pakistan, 90% in Bangladesh, 93% in Turkey, 56% in Saudi Arabia, and 76% in Jordan say women should be able to vote without any influence or interference from family members.

■ the right to hold any job for which they are qualified outside the home. Malaysia, Mauritania, and Lebanon have the highest percentage (90%); Egypt (85%), Turkey (86%), and Morocco (82%) score in the 80% range, followed by Iran (79%), Bangladesh (75%), Saudi Arabia (69%), Pakistan (62%), and Jordan (61%).

■ the right to hold leadership positions at cabinet and national council levels. While majorities in the countries surveyed support this statement, respondents in Saudi Arabia (40%) and Egypt (50%) are the exceptions.

45 Carroll, J. (2005, February 25). Iraqi women eye Islamic law. The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved September 14, 2007, from http://www.csmonitor.com/2005/0225/p07s02-woiq.htmlWhile Sharia is commonly depicted as a rigid and oppressive legal system, Muslim women tend to have a more nuanced view of Sharia, viewing it as compatible with their aspirations for empowerment. For example, Jenan al-Ubaedy, one of the 90 women who sat on Iraq’s National Assembly in early 2005, told The Christian Science Monitor that she supported the implementation of Sharia. However, she said that as an assembly member, she would fight for women’s right for equal pay, paid maternity leave, and reduced hours for pregnant women. She said she also planned to encourage women to wear hijab and focus on strengthening their families. To Ubaedy, female empowerment is consistent with Islamic values.45 (pp. 50-52, bolded text is repeated in box quotes in the book)

What Do Muslims Mean when they say they Support Sharia?

Continue reading “Most Muslims Support Sharia: Should We Panic?”