Imagine for a minute that you’re administering a test on the history of English literature, and one of your questions asks the students to explain in a short essay the meaning of word bowdlerize. Now imagine I’ve taken your test, and my essay begins:

“To bowdlerize something means doing what Thomas Bowdler did.”

I’m off to a bad start. But it gets worse. I continue:

“We can debate about why he expurgated Shakespeare’s plays, but what matters is what not why he did it.”

Then, oddly, I cite Aristotle’s four causes as if they have any relevance to the meaning and history of a word. Next, I veer off into a discussion about what other bowdlerizers have done.

“Some were offended by sexual innuendo, while others were put off by curse words and impiety. But it doesn’t matter why they did what they did, nor does it matter what the effect was. What they all did in common is the same one thing: expurgate works of literature. A trend begun by Bowdler. And thus so called.”

If I were you, I wouldn’t give me any points. The tiny part I happened to get right is overshadowed by the rest. We’ll see why as we go on.

Euhemerism, again

Richard Carrier, in his recent “Brief Note on Euhemerization,” provides a helpful TL;DR, which begins:

Euhemerization is doing what Euhemerus did: convert a non-historical deity into a deified historical man (in contrast to deification, which is when an actual historical man is converted into a deity).

Everything after the colon is generally correct, albeit incomplete. But in the first part of the sentence Carrier commits the same error I did concerning the word bowdlerize. He has demonstrated a rather extreme case of the etymological fallacy. Usually, that would mean that he knew the original meaning of the word and discounts the current meaning. However, in this case, he has gone all the way back to the word’s eponymous roots.

That isn’t how English works. That isn’t how any language works. Words gain meaning through usage, which explains why Oxford, Collins, Merriam Webster, et al. keep vast repositories of lexical citations. You can’t understand what a word means without knowing how people use it. Living languages are not prescribed; they are described.

Further, when a word is a term of art — such as bowdlerize and euhemerize — it matters how professional practitioners in the relevant fields use them. When experts in literature say somebody bowdlerized a poem, a novel, a film, etc., they mean more than just cutting out the naughty bits. It makes a difference why and how the self-righteous censor did it. For a clearer understanding of what the word means, you can hardly do better than the article on Thomas Bowdler in the Encyclopedia Britannica of 1911:

The official interpretation is “to expurgate (a book or writing) by omitting or modifying words or passages considered indelicate or offensive.” Both the word and its derivatives, however, are associated with false squeamishness. In the ridicule poured on the name of Bowdler it is worth noting that Swinburne in “Social Verse” (Studies in Prose and Poetry, 1894, p. 98) said of him that “no man ever did better service to Shakespeare than the man who made it possible to put him into the hands of intelligent and imaginative children,” and stigmatized the talk about his expurgations as “nauseous and foolish cant.”

Well, I said you could hardly do better, but I think the post at tvtropes.org is even clearer:

But true Bowdlerizing starts when you actually lower the quality of the art or story in some way in the editing, sometimes as little as spoiling jokes or perhaps making villains not look quite as evil, but escalating to damaging the plot, making dialogue confusing, and making heroes look pure and shiny. And at its very ‘best,’ it can make a situation less acceptable.

Where I failed

I wrote in my short essay that it didn’t matter why Bowdler did what he did; only the “what” matters. That’s wrong at its core. It actually doesn’t matter what Bowdler actually did or why he actually did it. What matters is what people thought he did. In fact, if you do a little research on the matter, you’ll find that many historians now think his sister, Henrietta, probably made most if not all of the “improvements” to Shakespeare’s works.

But my definition really misses the mark because I mistakenly assumed that my iffy understanding of the word’s etymology trumps its usage. If you’ve ever argued with somebody who “knows” the real meaning of the word decimate because he took a semester of Latin, you know how hard it is to convince some people how human language works. It isn’t wrong to define a word by its usage. In fact, that is the only valid way to define a word.

I also failed because I rejected its primary characteristics as secondary and superfluous. “Expurgation” is a tolerable definition for a pocket dictionary, but understanding the term in its full literary sense means that I have to mention the false squeamishness imputed to bowdlerizers, and the ruined works they leave in their wake. Nor is it simply the removal of words or sentences that offend; it includes replacing words that might make good Christian ladies blush.

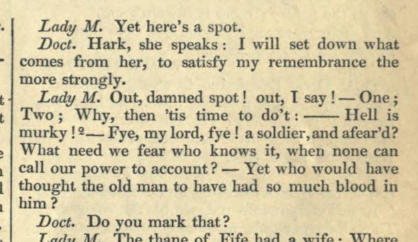

By the way, you may have read that Bowdler changed “Out, damned spot!” to “Out, crimson spot!” But that appears not to be the case, as you can see here:

Bowdlerism resembles euhemerism in that today both exist mainly as accusations. Nobody will proudly announce, “Hey! I just bowdlerized your book!” Similarly, when you see somebody use the word euhemerize today, they’re often accusing people of hyper-rationalizing, taking myths or legendary figures and theorizing about historical people as plausible antecedents.

Where Carrier thinks I failed

Carrier says that in my earlier post on Euhemerism, my analogy to Darwinism fell flat.

This is the problem with trying, as Widowfield does, to create an analogy between Darwinism, which is by definition not teleological, with an actual goal-oriented human activity. The latter differentiates between the act itself and its purpose. And as such, the same act (smelting steel, say) can be turned to many more purposes than its originators intended or imagined (you can smelt steel to make swords, plowshares, or literal flying machines). What you create is different from how you use it. Euhemerus did not invent his idea, but he popularized it. How people thus inspired then used that idea varied, as each user had their own goals, which his idea could be turned to accomplishing.

By comparing Darwinism to euhemerism, I had merely hoped to show how various people have misused both terms. In most cases, they misuse them because they don’t know their defining characteristics. Euhemerus’s method caught on in the Greco-Roman world, first and foremost, because it offered a naturalistic explanation for the gods. Carrier confuses this defining characteristic with a variable result.

Different people may smelt steel and end up with a sword or a pruning hook. Correspondingly, when Eusebius rationalized pagan gods as ancient kings, he did it to discourage people from worshiping them. But medieval European noblemen rationalized legendary demigods in order to claim descent from heroes. The defining characteristic remains the same, but the motives and outcomes are different.

In any case, as I said above, usage determines meaning. And in the case of a term of art, it matters especially how experts use it. As an example, in Utter Antiquity: Perceptions of Prehistory in Renaissance England, Arthur B. Ferguson writes:

Euhemerus himself had satisfied the naturalistic instincts never far from the surface of Greek culture by popularizing the idea that the gods had once been mortals deified by a grateful people for some signal service; and the idea continued to satisfy those in later centuries who, for one reason or another, likewise preferred to explain the gods in quasi-historical terms rather than as fantasies born of fear or favor. Palaephatus, his successor as a prophet of euhemerism, showed how obviously fabulous elements in the historical fables could be explained away, leaving standing a true history. And Dioclorus Siculus, whose universal history, though pagan, enjoyed a considerable currency in the early church, went one step further than Palaephatus by retelling the stories of the gods as though they were chapters in the history of the world. (Ferguson, 1993, p. 13, emphasis mine)

Will the real euhemerists please stand up?

Historians such as Ferguson, as well as anthropologists, sociologists, and classicists agree. Euhemerism is rationalization by the invention of historical figures. Ironically, while Carrier mistakenly calls Mark a euhemerist, he seems to have missed the fact that real euhemerists walk freely among us today.

Can you think of anyone who rationalizes “obvious fabulous elements in the historical fables”? Who do you know that explains away miraculous material in ancient texts, “leaving standing a true history”? That’s right. All of the historicists who vigorously insist that they can carve away the implausible parts of the New Testament and leave behind the bare bones of the real Jesus are euhemerizing him. They’re not “doing what Euhemerus did,” but rather doing what euhemerizing has come to mean through its usage — which, by the way, is amply demonstrated in the historical record.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

1. “Euhemerization is doing what Euhemerus did: convert a non-historical deity into a deified historical man …”

2. “Euhemerus … populariz[ed] the idea that the gods had once been mortals deified by a grateful people for some signal service; and the idea continued to satisfy those in later centuries who, for one reason or another, likewise preferred to explain the gods in quasi-historical terms rather than as fantasies born of fear or favor” (Arthur B. Ferguson, ‘Utter Antiquity: Perceptions of Prehistory in Renaissance England’)

3. “All of the historicists who vigorously insist that they can carve away the implausible parts of the New Testament and leave behind the bare bones of the real Jesus are euhemerizing him.”

I think these sentences all refer to the same thing – they only differ in tense ie. chronological terms: past or present tense. Euhemerus is recognized as being one of the first to do it, to Greek gods, at a particular point in time (albeit in the past ie. the 3rd C. bce). Currently, Carrier is proposing that the synoptic writers (such as ‘Mark’) did it (in the past ie. in the 1st C ce).

And Tim Widdowfield is right in (3) – those proposing “they can carve away the implausible parts of the New Testament and leave behind the bare bones of the real Jesus are euhemerizing him” (ie. they are recently or currently attempting to euhemerize Jesus).

I would change one sentence (in the penultimate paragraph) – Euhemerism is rationalization by the *proposition* that gods were once historical figures. ie. the proposition they were once real, on-earth tangible, historical figures.

And to use Arthur B. Ferguson’s terminology ie. “to explain the gods in quasi-historical terms” is what both Carrier proposes that the synoptic gospel writers did, and what Christians have done and do.

Lastly, I would quibble with Ferguson’s statement that “Euhemerus … populariz[ed] the idea that the gods had once been mortals deified by a grateful people for some signal service ..” — The idea that “the gods had once been mortals” has been attributed to Euhermus, but it may have been popularized after Euhemerus.

Euhemerization ironically also became a means by which early Christians dismissed non-Christian gods b/c they had been portrayed as ‘having been *only* deified people’; which is quite ironic given, as Tim points out, the recent (current) push to historicize Jesus by ‘mortalizing’ Him.

MrHorse: I would change one sentence (in the penultimate paragraph) – Euhemerism is rationalization by the *proposition* that gods were once historical figures. ie. the proposition they were once real, on-earth tangible, historical figures.

I like it.

Indeed, the modern usage of ‘euhemerism’ is simply: ”… an approach to the interpretation of mythology in which mythological accounts are presumed to have originated from real historical events or personages. Euhemerism supposes that historical accounts become myths as they are exaggerated in the retelling, accumulating elaborations and alterations that reflect cultural mores.” (Wikipedia)

Thus, while the modern-day usage of the term ”euhemerism” is wider in scope than that used by Euhemerus (whose context was the Olympian gods) the principle involved remains the same. i.e. a naturalistic approach that understands the origin of the myths or gods to have been earthly.

Yes, on a literary use of the term, the expression re Carrier that ”Euhemerization is doing what Euhemerus did” is incorrect re the wider context in which the term is used today. But the problem re Carrier is not only that his usage is contrary to modern-day usage but his claim that he is doing what Euhemerus did is also contrary to what Euhemerus did.

Carrier: ”Euhemerus took celestial (ahistorical) gods (Zeus and Uranus) and then turned them into historical men. Not the other way around. Therefore, anyone who does that is doing what Euhemerus did.”

Carrier’s position is top down while Euhemerus had a bottom up approach to the Olympian gods i.e. their origin was believed to be earthly.

Carrier:

”At the origin of Christianity, Jesus Christ was though to be a celestial deity much like any other.

“Like many other celestial deities, this Jesus ‘communicated’ with his subjects only through dreams, visions and other forms of divine inspiration (such as prophecy, past and present).

“Like some other celestial deities, this Jesus was originally believed to have endured an ordeal of incarnation, death, burial and resurrection in a supernatural realm.

“As for many other celestial deities, an allegorical story of this same Jesus was then composed and told within the sacred community, which placed him on earth, in history, as a divine man, with an earthly family, companions, and enemies, complete with deeds and sayings, and an earthly depiction of his ordeals.”

Bottom line in all of this is that Carrier has looked to Euhemerism as support for his theory regarding the Pauline Christ figure being transformed, morphed, into the gospel Jesus. In effect, looking for historical and scholarly support for his theory – and when that support is not there – he has bowdlerize both the work of Euhemerus and the modern-day use of euhemerism.

( Carrier can drop his misuse of euhemerism and base his mythicist theory on a historizing of the Pauline celestial Christ figure…….)

Euhemerism is a naturalistic approach to myths – as such, although it can be used against the Jesus historicists, it would not, necessarily, produce the outcome mythicists might be seeking. The theory of Euhemerus is that the Olympian gods had an earthly origin. Whether that belief is true or false can only be established with historical evidence – the lack of which does not deny historicity – only that it cannot be proved. So, while the Jesus historicists are euhemerists – that does not negate, in itself, their historicist claims for the gospel JC.

MH: “Bottom line in all of this is that Carrier has looked to Euhemerism as support for his theory regarding the Pauline Christ figure being transformed, morphed, into the gospel Jesus. In effect, looking for historical and scholarly support for his theory – and when that support is not there – he has bowdlerize both the work of Euhemerus and the modern-day use of euhemerism.”

You have touched on exactly the point I’ve been trying to make. On Carrier’s blog I see accusations of “policing” terminology. That is not my intent. I see misuse of words all the time, and normally say nothing about it. But the problem here is that, as you say, he’s looking for historical antecedents to support his claim. Unfortunately, no matter how we stretch the term, I just don’t see how you can call Mark a euhemerist.

And despite Carrier’s protestations that he uses the term consistently and intelligibly, sentences like this would tend to disconfirm that notion: “First, a deity can easily be euhemerized from day one. It does not require any time lag at all.” (OHJ, p. 249)

A favor I have to ask, if you please Tim. Can you fill in these blanks briefly, just to help me follow what’s happening in this debate?

“What Euhemer did was to __________________________, but what Mark did instead was to ______________________________”

Thank you!

(1) What Euhemerus did was probably to write an imaginary travelogue as a way of advancing the theory that the Olympian gods were, at one time, ordinary humans — kings that people thought so highly of, that they worshiped them as if they were deities. Presumably, everyone but the Panchaeans had forgotten about this “real” history until he rediscovered their Sacred Inscriptions.

Carrier writes, “We don’t actually have the text in question, only hostile reactions to it, which quote selectively from it or paraphrase it (how accurately we can’t tell).” It’s true that we don’t have the original text, but we have more than hostile reactions to it. For instance, we can be certain that Diodorus Siculus agreed with him.

And, in fact, Euhemerus’s text was extremely popular. How do we know?

Oddly, Carrier says we can’t know why Euhemerus did it, but admits that Plutarch accused him of impiety and atheism. Well, yeah. That’s what happens when you rationalize gods by inventing stories about them being humans who once lived on Earth. The process of de-mythologizing the gods naturally upset some people.

(2) What Mark did instead was write a book about a powerful messianic character. I’m still not convinced by the arguments that Mark had a high Christology. Nor do I think he believed in the pre-existence of Christ. Instead, I think he saw Jesus as the last and greatest prophet of the age whose death would bring about “a ransom for many.” He may or may not have thought Jesus would be elevated to the status of Son of Man, the cosmic judge who would appear at the end of the age.

I don’t think he believed he was creating some backstory for a known pre-existing god or semi-divine figure. Nor is there any way he was rationalizing said divine character into a mere mortal who did good works. No, he saw Jesus as the adopted son of God (revealed at the baptism) and the “holy one of God” (as witnessed by the demons).

So, Jesus was chosen by God, but he was still a man — a prophet. Now, sometimes I toy with the idea that the entire gospel of Mark was actually an allegorical story about the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, but I’m not prepared to argue that yet.

Carrier is saying, I think, that Mark wrote the narrative about a human – Jesus – to anthropomorphize the notion of a saviour Christ (Carrier asserts that this was the entity that Paul was writing about).

I presume that Carrier is inferring that the Pauline texts were then redacted to add the name Jesus to the name Christ, or put the the name Jesus in the place of Christ. this would have been relatively easy to do as there is not much biography of Jesus is Paul.

No, Carrier thinks “Jesus” was in there from the beginning. He thinks (suspects?) it’s taken from a reference to a “Jesus” in a prophecy from, IIRC, Zechariah. That’s the same place where Carrier says Philo finds a messianic figure.

Yes, though that it is an allusion by Carrier to an allusion by Philo to an allusion in Zecharian; and Philo and Zecharian are alluding to a nebulous entity.

Thanks for clarifying…

I recognize there are some difficulties with the use of the term Euhemerization, and I take your point that it can matter what word is used since this can have implications for whether there are historical precedents.

But suppose Carrier is right that Mark was written intentionally as an allegorization (or something) of the actual Christ _as though_ he had lived on Earth (or as an allegory for _what Christians_ are supposed to be like). I thought his point was just that this activity, in itself, finds historical precedent in Euhemerization, _exactly_ because it is (as Euhemer proposed) the setting of heretofore-thought-of-as-cosmic figures in a mundane setting.

Well, it’s important to understand that the reason Euhemerus’s work became popular early on was that the intelligentsia at the time was ready for some sort of rational explanation for the old gods. The rationalization movement generally split into two ways to rationalize them:

1. The gods represent allegorical understandings of natural forces, emotions, etc.

2. The gods were once real people who lived on earth. Gods in the deep, mythic past were converted into humans in the legendary past. (

One problem with comparing what Mark was doing with euhemerism (if you’re calling the gospel an allegory) is that when you euhemerize a god, you’re creating a concrete, de-mythologizing rationalization. I just don’t think Mark did that.

I guess gMark was one of the least novelistic of the gospels. Though we do see a lot more Jesus dialogue than the Jesus of Paul?

Tim said: “when you euhemerize a god, you’re creating a concrete, de-mythologizing rationalization.”

I somewhat agree, but the problem is that when one is talking about gods it’s hard for much of the discussion to be fully rational.

Moreover, euhemerizing a god hardly ever fully de-mythologizes them.

If Carrier is right about Mark creating a Jesus that humanizes/anthropomorphizes a previous celestial being, Mark would have been creating a new notion of a god: *unless* Mark was not proposing any god-like qualities to his Jesus [and it was only later writers that made Marks Jesus into a deity] (I think that’s unlikely).

Mark partially but not completely demytholigized. He wanted a more human-seeming God.

Wikipedia is vague on this (or it was when I last looked and it seems to be the same now as it was then).

Wikipedia lacks specifics.

Thanks Tim for adding these final words :

Can you think of anyone who rationalizes “obvious fabulous elements in the historical fables”? Who do you know that explains away miraculous material in ancient texts, “leaving standing a true history”? That’s right. All of the historicists who vigorously insist that they can carve away the implausible parts of the New Testament and leave behind the bare bones of the real Jesus are euhemerizing him. They’re not “doing what Euhemerus did,” but rather doing what euhemerizing has come to mean through its usage — which, by the way, is amply demonstrated in the historical record.

Maryhelena writes:

The theory of Euhemerus is that the Olympian gods had an earthly origin. Whether that belief is true or false can only be established with historical evidence – the lack of which does not deny historicity – only that it cannot be proved.

I disagree (kindly), because it’s a FACT that the Olympian gods are mythical. Period. So, we can call the Jesus historicists as ‘modern euhemerists’ only if I have already proved that Jesus is a myth.

Given the correct definitive definition of euhemerism:

Euhemerism is rationalization of mythological figures by the invention of historical figures behind them.

the question raised by Tim is : were the Gospel writers real euhemerists?

I think that to answer only ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to that question means to do a fallacy of false dichotomy.

Under the Carrier mythicist paradigm, it’s true that the Gospel writers do not urged outsiders to rationalize their Gospels. but it’s equally true that they were selling to outsiders their gospels as ”remembered history”. This implies logical historical effects.

For each listener of the first Gospel nothing did remain but to choose between three options:

1) to remain non-Christian, or to deny everything as mere fraud.

2) to be non-Christian, or to rationalize the Gospels (à la Celsus, à la Tacitus) by inventing a ”historical Jesus” of their liking,

3) to become a Christian outsider, and believe in the literal truth of all the Gospel.

Therefore Carrier can be still right: if Jesus didn’t exist, then the author of the first Gospel forced his not-Christian listeners to become euhemerists velim nolim.

Maryhelena writes:

The theory of Euhemerus is that the Olympian gods had an earthly origin. Whether that belief is true or false can only be established with historical evidence – the lack of which does not deny historicity – only that it cannot be proved.

————————–

I disagree (kindly), because it’s a FACT that the Olympian gods are mythical. Period. So, we can call the Jesus historicists as ‘modern euhemerists’ only if I have already proved that Jesus is a myth.

———————-

MH: I disagree. 1) The theory of Euhemerus is that the *origin* of the Olympian gods was earthly. That’s the theory – you can’t change the theory to suit your own position. That’s what Carrier has done – bowdlerize it. 2) The Jesus historicists can be called euhemerists irrespective of whether Jesus was historical or not.

—————

Given the correct definitive definition of euhemerism:

Euhemerism is rationalization of mythological figures by the invention of historical figures behind them.

the question raised by Tim is : were the Gospel writers real euhemerists?

I think that to answer only ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to that question means to do a fallacy of false dichotomy.

Under the Carrier mythicist paradigm, it’s true that the Gospel writers do not urged outsiders to rationalize their Gospels. but it’s equally true that they were selling to outsiders their gospels as ”remembered history”. This implies logical historical effects.

————————-

MH: I don’t think the gospel writers were euhemerists. It is those who interpret the gospel story as being historical that are the euhemerists. The basis of the gospel story is political allegory. That’s the foundation upon which is added mythology, theology, philosophy, symbolism etc.

———————

For each listener of the first Gospel nothing did remain but to choose between three options:

1) to remain non-Christian, or to deny everything as mere fraud.

2) to be non-Christian, or to rationalize the Gospels (à la Celsus, à la Tacitus) by inventing a ”historical Jesus” of their liking,

3) to become a Christian outsider, and believe in the literal truth of all the Gospel.

————————-

MH: Not so. Political allegory is an option. Actually, political fiction is an option that Carrier makes mention of – saying that ‘it suits the gospels well’.

page 53/54 of On the Historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reasons to doubt.

”Unlike the minimal theory of historicity, however, what I have just said

is not strictly entailed. If ‘Jesus Christ began as a celestial deity’ is false,

it could still be that he began as a political fiction, for example (as some

scholars have indeed argued-the best examples being R.G. Price and

Gary Courtney). But as will become dear in following chapters (especially Chapter 11), such a premise has a much lower prior probability (and thus is already at a huge disadvantage over Premise 1 even before we start examining the evidence), and a very low consequent probability (though it suits the Gospels well, it just isn’t possible to explain the evidence in the Epistles this way, and the origin of Christianity itself becomes very hard to explain as well). Although I leave open the possibility it may yet be vindicated, I’m sure it’s very unlikely to be, and accordingly I will assume its prior probability is too small even to show up in our math. This decision

can be reversed only by a sound and valid demonstration that we must

assign it a higher prior or consequent, but that I leave to anyone who thinks it’s possible. In the meantime, what we have left is Premise 1, such that if that is less probable than minimal historicity, then I would be convinced historicity should be affirmed (particularly as the ‘political fiction’ theory already fits historicity and thus is not really a challenge to it-indeed that’s often the very kind of fiction that gets written about historical persons)”

——————–

Therefore Carrier can be still right: if Jesus didn’t exist, then the author of the first Gospel forced his not-Christian listeners to become euhemerists velim nolim.

————————

MH: Carrier is wrong. Full stop! The gospel writers wrote a story – it’s up to us to read that story as history, as mythology or as political allegory. Reading that story as history or mythology is the easy way out. Reading that story as a political allegory requires that we first consider history and then attempt to understand the story the gospel writers wrote. That the gospel story became viewed as history is not the fault of the gospel writers. What happened to their story after they died has more to do with the fading of Jewish history from memory than it has to do with any ulterior motive on their part. Let’s not blame the gospel writers for our own inadequacy in understanding what they wrote….

You are assuming that there is no way of knowing the existence or not-existence of Zeus, Uranus, etc.

While it is a FACT that Zeus, Uranus, etc, didn’t exist.

Therefore to rationalize Zeus, Uranus, by inventing or imagining a historical Zeus, Uranus, is pure invention masked as rationalist effort.

Therefore we can call the modern historicists as ‘euhemerists’ only and only if we have already proved (or assumed) that Jesus didnt’exist.

Therefore Tim is right: ‘Mark’ is not an euhemerist, because he didn’t claim to be a rationalist or a rationalizer when he introduced his first Gospel Jesus.

But ‘Mark’ moved his not-Christian listeners to become euhemerists, if they were not Jesus mythicists and if they were not converted to Christianity.

Therefore the logical conclusion is that, under the Carrier minimal mythicism, the real Jesus euhemerists were the historicist Pagans.

Conclusion: Maryhelena (with his thesis of political fiction: ‘Jesus’ would be an asmonean king existed 100 years before Christ) is an euhemerist just as Celsus, as Tacitus (if the Testimonium Taciteum is authentic and gospel-derived), as Porphiry, etc.

Giuseppe

Re-posting the same post here that you did on Peter Kirby’s forum will get the same response from me.

Carrier is wrong – deal with it.

My reply there, too. In short: Carrier is wrong, but that someone euhemerized Jesus after the reading of Mark would be the logical correction of Carrier on his use of euhemerism (if he accepts the Tim’s definition of it), I think.

Tim: ”Euhemerism is rationalization by the invention of historical figures”.

Invention?

Wikipedia: ..”mythological accounts are presumed to have originated from real historical events or personages”.

I read that as saying that the theory of Euhemerus relates to presuming that the Olympian gods were once mortal humans; in other words a *belief* that the Olympian gods were once humans. Thus, what is ‘invented’ is the mythology i.e. the stories about them. Is not the belief and the invented mythology, the story, two separate issues? Belief needs no evidence in said human origin of the gods – while invention relates to providing, as it were, a back-up supporting mythological story. Would it not be contrary to Euhemerus to refer to euhemerism as ‘invention’ when the theory of Euhemerus is founded on a presumption, a belief, and not on simple invention?

—–

Wikipedia, on euhemerism, has an interesting quote from Robert Price:

”When we are done dismantling the records and we begin ghoulishly picking through the scanty remains for clues to an underlying “historical Jesus,” like people scavenging gold from the teeth and fingers of the battlefield dead, are we perhaps engaging in Euhemerism?”

Nice….. Price is using Euhemerism contrary to Carrier’s usage 😉

M.H.: Would it not be contrary to Euhemerus to refer to euhemerism as ‘invention’ when the theory of Euhemerus is founded on a presumption, a belief, and not on simple invention?

Nobody seriously believes Euhemerus visited Panchaea. He may have believed in his own theory, but the evidence he provided was pure invention.

M.H.: Price is using Euhemerism contrary to Carrier’s usage.

Carrier’s usage is so elastic as to be incomprehensible.

”When we are done dismantling the records and we begin ghoulishly picking through the scanty remains for clues to an underlying “historical Jesus,” like people scavenging gold from the teeth and fingers of the battlefield dead, are we perhaps engaging in Euhemerism?” —

No!

Well then, take the issue up with Robert Price – or, for that matter, Wikipedia…

Carrier has made this statement in reply on his blog –

“The Christians did not equate Jesus with Yahweh for at least half a century or more. They equated him with a created archangel subordinate to God. Still a divinity. And thus in pagan terminology a god. But not the (supreme) God.” http://freethoughtblogs.com/carrier/archives/10004#comment-1059242

He may have spoken rashly and, in the heat of the moment, forgotten about the riotous diversity among the earliest followers of Jesus. Saying “the Christians” thought this or that in the first century is anachronistic. Some thought he was just a man. Others argued he was a created archangel, but others said that notion was completely wrong — he was begotten, not created.

Paul talks about Jesus being instrumental in the creation of the universe, but as a separate being.

Still, his emphasis on being “born of a woman” would indicate to me that he didn’t view Jesus as a created being. Probably divine and probably subordinate, but not angelic and not created.

If indeed “born of a woman” is original, as Ehrman himself has doubted: http://vridar.org/2014/01/16/the-born-of-a-woman-galatians-44-index/

Good point. So the question would then center around Paul’s understanding of sonship. Did he think God created an archangel, Jesus, and then adopted him as his son? Or was he a divine emanation, of the same substance, and not created?

I never got the impression that Paul thought of Jesus as a created archangel, but I could be wrong, of course.

“Saying “the Christians” thought this or that in the first century is anachronistic.”

True. That applies well beyond the first century too.

And Paul doesn’t seem to be much help, either.

Pre-Christian theology – both Jewish & otherwise – as well as so-called inter-Testamentary literature, such as that of Philo & Aristides (& possibly Plutarch), is very unclear what the various entities were: it seems various entities were considered to be fluid or interchangeable.

Time to re-read Margaret Barker’s The Great Angel.

New comment from Carrier: ‘Any god who is worshipped before being distinctly placed in human history, and then is placed in history, as a human later deified, has undergone the process Euhemerus used, and has therefore been Euhemerized.’

So there we have it. Euhemerism and Carrier’s mythicist theory are joined at the hip…or so Carrier believes….

————–

OHJ:

1. At the origin of Christianity, Jesus Christ was thought to be a celestial deity much like any other.

4. As for many other celestial deities, an allegorical story of this same Jesus was then composed and told within the sacred community, which placed him on earth, in history, as a divine man, with an earthly family, companions, and enemies, complete with deeds and sayings, and an earthly depiction of his ordeals.

——————

‘..later placed in history’? This is of course a fundamental premise of Carrier’s position i.e. the Pauline celestial christ preceded the gospel Jesus. But Doherty held that an early Q community already had a Jesus type figure, albeit an invisible Jesus figure. (Wells having a flesh and blood Galilean preacher). Carrier gives Q the boot and thereby loses any earthly connection – leaving him only with Paul’s celestial christ figure – a figure which he somehow has to get down to earth….

Doherty maintained that: ‘ The entire teaching, miracle-working and prophetic content of the Gospels is derived not from Paul, whose celestial Christ had nothing to do with such things, but from an imagined founder of the Q movement..’ (FRDB)

It is only in a metaphorical sense that one can say that Euhemerus brought the gods down to earth. The Olympian gods stayed where they were thought to be – the Euhemerus theory claims only that their *origin* was earthly.

It does not matter that the theory Euhemerus proposed, that the *origin* of the Olympian gods was earthly, was written or conceived later than their present abode in a celestial realm. Euhemerus was interested in their *origin* not their present situation.

Even if, for the sake of argument, the Pauline writings are early and the gospel writing late – this does not equate to gospel writers historicizing the Pauline celestial christ. That Paul, seemingly, has no interest in the life of an earthly Jesus figure, does not translate into he does not know the gospel story. Paul’s context is simply different than the context of the gospel story. To assume Paul does not know the gospel story is unfounded speculation. Dating documents is never going to date the material they contain. The gospel story and the Pauline story, two very different contexts, need to be evaluated according to their own contexts not superimposing the context of one upon the other. As some mythicists are wont of saying – don’t read the gospels into Paul – then, likewise, don’t read the Pauline story into the gospel story.

Euhemerism cannot save Carrier’s mythicist theory. In Carrier’s hands the ahistoricist/mythicist theory has, in effect, suffered self combustion. 😉

So, duly following Vridar’s attacks on Carrier, Maryhelena has firmly disproved mythicism? Carrier especially?

Note problems with her account.

1) Dougherty mentions Q as in effect, giving an earthly Jesus. But says Q is “imaginary”.

2) As defined correctly by usage, not origin, Euhemerization has many variations in meaning. It means assigning an historical bio to a figure, either a) correctly, or b) incorrectly.

3) Carrier believes it was an incorrect Euhemerization. Which would be an people like Mark falsely assigning historical details to Dougherty’s celestial, platonic Jesus. No problem there.

Whatever Carrier says at times, Euhemerization theory often holds that 1) the gods were originally humans, heroes, whose qualities became exaggerated, godlike, in later folk and other tales. But 2) it can also suggest that, in false Euhemerization, the opposite: originally vague celestial ideas, are later wrongly thought to be concrete.

Carrier correctly looks at both concepts. Though his formal definitions may stress only one, or the other.

By the way? I never criticise Carrier. By criticizing Carrier too much, I feel that Mythicism, Vridar, will soon undercut itself, and destroy its own leading proponent. As it has very nearly done here . We see the fruits of that, in Maryhelena’s arguments.

Damon: “Vridar’s attacks on Carrier”

Oh dear. Let’s not be so dramatic. I have an issue with the misuse of a term. It isn’t an “attack.”

Damon: “By the way? I never criticise Carrier. By criticizing Carrier too much, I feel that Mythicism, Vridar, will soon undercut itself, and destroy its own leading proponent.”

Self-censorship is the worst kind of censorship. Let’s be clear. Vridar is not criticizing Carrier. I don’t know for sure what Neil’s position is. Tim (that’s me) is pointing out a problem with the use of the word Euhemerism.

You seem to be implying that Carrier would turn on Vridar simply because we disagree on technical points. I believe he has too much integrity to do that. Besides, a good thesis can withstand scrutiny; what doesn’t kill it makes it stronger.

‘Any god who is worshipped before being distinctly placed in human history, and then is placed in history, as a human later deified, has undergone the process Euhemerus used, and has therefore been Euhemerized.’

So how does this definition fit with “instant euhemerization”?

Well, Carrier like to have his cake and eat it as well. Same day or centuries later 😉

How about this for the celestial demons also being euhemerized!

OHJ: footnote: ‘See Carrier, Proving History, pp. 151-55. Mark’s euhemerization would logically transfer Jesus’ demonic enemies to earthly ones, leading to the allegory of internecine betrayal in the Judas narrative (where the whole world conspires to kill him: Romans, Jews and ‘Christians”)

Methinks Carrier is tying himself up in knots with his Pauline celestial christ figure being euhemerized as the gospel Jesus.

Thomas Brodie had no need of Pauline theology/philosophy when deciding for the ahistoricist position – the gospels are sufficient for that purpose. Paul, to my mind, is a red-herring as far as the gospel story is concerned…Rather than wasting time arguing which was first – Paul or the gospel story – we should be dropping this chicken and egg scenario and deal with the reality we face. Although they are related, the Pauline writings and the gospel story are two very different things; different things which need to be evaluated on their own individual merit.

The gospels make a historical claim. A Roman agent was involved in the crucifixion of a man they labeled ‘king of the Jews’. That claim cannot be rejected by advancing a theory of a celestial christ figure being morphed into an invisible, mythological, ‘earthly’ man. The gospel claim has to be answered by a historical inquiry not a theological one.

Euhemerization is an historical, and historically documented process. 1) Euhemerus himself was likely an historical figure; 2) and modern history confirms that sometimes there are real people behind apparent myths. And conversely, 3) sometimes what appear to be real people, are myths, fictions, based on human dreams.

The issue boils down to whether a god was turned into a man, or a man into a god, whatever fits all the available evidence most satisfactorily. Can the impression from Paul’s letters that Jesus had been a man be discounted, except by postulating that contrary data therein must have been interpolated?

1) Paul’s manlike Jesus is extremely sketchy, compared to the gospels; without much detailed dialogue from Jesus. Furthermore, 2) Paul distinguishes between this “earthly” Jesus of the “flesh”, and a perhaps better Jesus and God. Who are invisible “spirit.” The spirit is favored.

Paul and others like John distinguish in effect, between Dogherty’s two Jesuses. And he by far stresses the spiritual, heavenly one. Consistent with Dougherty.

Any possible references in Paul to an earthly Jesus, are extremely general, and sketchy: heard in a vision, etc.. Such mentions are arguably not even really earthly at all. Or are attributable to folk habits of taking metaphors literally. As well as to interpolation.

I think e.g. Earl Doherty’s “lower world” and “second Adam” arguments only confirm that Paul thought that Jesus also had a human existence on earth in the flesh as a descendant from David, with followers to whom he “appeared” after his betrayal, last meal and execution, whom he had previously opposed and two of whom he eventually met in person. Paul has an “incarnation” theology different from John, but it entails ipso facto “carnem”.

I do adhere to the view that Daniel with its passages on the Son of Man and the “Messiah” being cut off played an important in Christian origins.

There might be a very, very minimal physical-seeming Jesus in Paul. But not to 1/20 the degree we are given one in the gospels. Where Jesus cries and sweats and spits, walks and talks, continually. And looks only slightly less material than a typical character in a typical modern realist novel.

Consider the proportions. The proportion of naturalistic portrayal, imagery, vs. abstractions. In the synoptic gospels vs. Paul.

There is a decisive difference between deifying someone who really existed and deifying someone who never existed at all. 20/1 on bookie’s odds.

I recently saw a use of the word euhemerization in a paper published in 1941. I didn’t know what it meant in context but couldn’t see how euhemerization could be used there the way Carrier it. The paper was `Thallus: THE SAMARITAN?”, Rigg, HA, Harvrad Theological Review, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Apr., 1941), pp. 111-119. There Rigg writes of Thallus (a first or second century writer who is supposed to have mentioned the darkness at the crucifixion of Jesus): “[Thallus] seems to have been a euhemerizer of ancient Greek and Oriental history and mythology”.

But more importantly Rigg wrote about Africanus (a writer who claimed Thallus had mentioned the darkness) that Africanus “resents his [i.e. Thallus’s] apparent euhemerization, at one point, of Christ”. I couldn’t make sense of that in Carrier’s meaning of the term “euhemerization”, but I see in light of what Neil Godfrey has written what Rigg meant. What Africanus objected to about Thallus is that Thallus (according to Africanus*) tried to explain the miraculous darkness as merely a natural eclipse of the sun.

So Rigg is using the word “euhemerization” to mean “explaination of the miraculous by means of the natural”.

And I entirely agree that if that is how scholars use the term, then that is what it means.

—————————————————————————————————–

*Carrier’s article on Thallus [JGRChJ 8 (2011–12) 185-91] argues that Africanus was mistaken about what Thallus actually wrote; that Thallus never mentioned Christ, but merely mentioned an earthquake and eclipse in present day Turkey.

Such a waste of time to argue about what a word means, especially when the word appears to be jargon. Carrier can call what he thinks Mark did by any term he wants, if he doesn’t mind confusing people. But if he is trying to say that what he thinks Mark did is common, and is trying to prove that by calling it by a common name, then that is invalid.

It reminds me of a stupid tactic used by a fringe group of economists who call themselves the Austrian school. They define inflation as “increase in the money supply”, while everybody else defines inflation as “increase in the price level” or “increase in the CPI” or the like. So the Austrians can and do say “increase in the money supply always causes inflation”, a tautology by their definition of inflation. But they can’t thereby prove that prices must right now be inflating at an enormous rate by pointing to the enormous increase in the money supply.