Previous in this series:

- Plato’s and the Bible’s Ideal Laws: Similarities 1:631-637 (2015-06-22)

- Plato’s and Bible’s Laws: Similarities, completing Book 1 of Laws (2015-06-23)

- Plato’s Laws, Book 2, and Biblical Values (2015-07-13)

- Plato and the Bible on the Origins of Civilization (2015-08-13)

—

Book 4 of Plato’s Laws

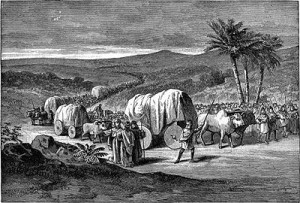

For Plato the ideal state must begin with the new citizens arriving to settle in a land that has long been uninhabited and that is well distant from potentially corrupting influences of any neighbouring state. They mustn’t have it too easy or materially abundant, though, or self-indulgence and the usual corruptions of wealth are sure to overtake them, so the land must be rugged enough to keep them working hard for their well-being.

The biblical authors likewise narrated a story of new laws being given to a people leaving one “home” and moving to settle in another but of course there was a significant difference.

The biblical authors likewise narrated a story of new laws being given to a people leaving one “home” and moving to settle in another but of course there was a significant difference.

They were placing an ideal set of laws upon a land that contained a mixed population and was surrounded by potentially corrupting kingdoms. The same author(s) knew well the problem, though, and stressed the absolute necessity to drive out all the inhabitants of the land (Deut 7) and avoid any marriages with their neighbours (Deut. 17:14-20) lest they be led astray from keeping their perfect laws. The whole meaning of “holiness” and being a “holy nation” is separation from others.

Ath. And is there any neighbouring State?

Cle. None whatever, and that is the reason for selecting the place; in days of old, there was a migration of the inhabitants, and the region has been deserted from time immemorial.

Ath. And has the place a fair proportion of hill, and plain, and wood?

Cle. Like the rest of Crete in that.

Ath. You mean to say that there is more rock than plain?

Cle. Exactly.

Ath. Then there is some hope that your citizens may be virtuous . . . . There is a consolation, therefore. . . owing to the ruggedness of the soil, not providing anything in great abundance. Had there been abundance, there might have been a great export trade, and a great return of gold and silver; which, as we may safely affirm, has the most fatal results on a State whose aim is the attainment of just and noble sentiments

In the story of Israel great wealth did flood the land in the time of Solomon so that “silver was as common as stones” (1 Kings 10:27) and that was the turning point in the kingdom’s history, as we know.

Purpose of the Laws

The ideal laws of both Plato and the Bible are said to be instituted to make people virtuous. They are not simply about maintenance of justice, keeping the peace and protecting sacred values but are intended to produce personal excellence of character or righteousness. This surely alerts us to a very strong probability that the Bible’s laws which had the same purpose were of philosophical/theological origin rather than being historically instituted as day-to-day law.

Ath. Remember, my good friend, what I said at first about the Cretan laws, that they look to one thing only, and this, as you both agreed, was war; and I replied that such laws, in so far as they tended to promote virtue, were good; but in that they regarded a part only, and not the whole of virtue, I disapproved of them. And now I hope that you in your turn will follow and watch me if I legislate with a view to anything but virtue, or with a view to a part of virtue only. For I consider that the true lawgiver, like an archer, aims only at that on which some eternal beauty is always attending, and dismisses everything else, whether wealth or any other benefit, when separated from virtue.

Compare Deuteronomy 6:25 and 4:6 Continue reading “Bible’s Presentation of Law as a Model of Plato’s Ideal”