To continue the theme of fundamental principles of historical reasoning this post selects points from Historical Evidence and Argument by David Henige (2005). They all come from the fourth chapter titled “Unraveling Gordian Knots”.

To continue the theme of fundamental principles of historical reasoning this post selects points from Historical Evidence and Argument by David Henige (2005). They all come from the fourth chapter titled “Unraveling Gordian Knots”.

Pyrrhonist scepticism

To begin, notice what scepticism means to Henige. He explains:

Skepticism takes many forms—I am concerned with pyrrhonist skepticism. In theory, and often in practice as well, the pyrrhonist doubts but seldom denies. Instead, he prefers to suspend judgment about truth-claims on the grounds that further evidence or insights might alter the state of play. Pyrrhonists demand that, to be successful, all inquiry must be characterized by rhythms of searching, examining, and doubting, with each sequence generating and influencing the next in a continuously dialectical fashion.7

As a result, issues are visited and revisited as often as needed. The result can be to strengthen probability or to weaken it — odds that might seem too risky for those who believe that progress must be inexorable.

The considered suspension of belief does not ordinarily pertain in matters that are self-evident or trivial, but expressly applies to cases where more than one explanation is possible.8

Given this caveat, the practical advantages of pyrrhonism are patent.

The most important is that declining to accept or believe keeps questions open as long as necessary. Practitioners learn to flinch when they meet terms like “certainly,” “without doubt,” “of course,” or “prove/proof” in their reading, seeing them as discursive strikes designed to persuade where the evidence, or its use, prove insufficient. They have learned that, since new evidence and new techniques are constantly coming forth, they are sensible to withhold final judgment.

7 Discussions of pyrrhonism include Naess, Scepticism; Vansina, “Power of Systematic Doubt;” Wlodarczyk, Pyrrhonian Inquiry.

8 For such practical limitations see Ribeiro, “Pyrrhonism.”

(My formatting and bolding in all quotations)

Anathematizing of doubt and doubters

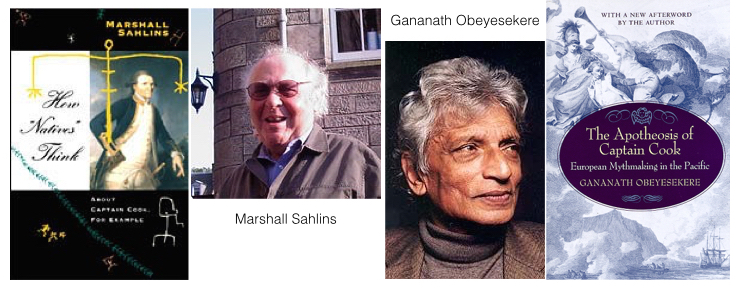

In scolding his most persistent critic, Marshall Sahlins asks: “[w]hy, then, this stonewalling in the face of the textual evidence?

Probably because [Gananath] Obeyesekere’s main debating game is a negative one, . . . the object being to cast doubt.”

I’m sure anyone who has read some of the intemperate responses of scholars outraged by Christ Myth or “mythicist” challenges to the traditional reading of Paul’s letters will hear clear echoes here. I’m also reminded of Emeritus Professor of New Testament Language, Literature and Theology Larry Hurtado’s complaint that my questions were only designed to sow doubt and served no constructive function.

Marshall Sahlins and Gananath Obeyesekere draw upon the same body of evidence — the accounts of the various eyewitnesses among Cook’s crew that were published on their return to England. Continue reading “The Positive Value of Scepticism — and Building a Negative Case — in Historical Enquiry”