These posts trace the evolution of Isaiah’s “Suffering Servant” from a poetic symbol for the nation of Israel into a dying and rising Messiah even before Christianity emerged on the scene. (See the Wikipedia article for background on the Servant Songs in Isaiah.) The previous post showed the apparent influence of the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53 upon the books of Zechariah and Ben Sirach/Sira. This post pauses to look at some background before resuming with the way the Book of Daniel adapted Isaiah’s Suffering Servant idea in the light of contemporary events — around 165/164 BCE. My source for these posts is

Hengel, Martin, ‘The Effective History of lsaiah 53 in the Pre-Christian Period’, in The Suffering Servant: Isaiah 53 in Jewish and Christian Sources (ed. Bernd Janowski and Peter Stuhlmacher; Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2004), pp. 75-146. (Bailey is responsible for translating Hengel’s essay into English and updating it in consultation with the author.)

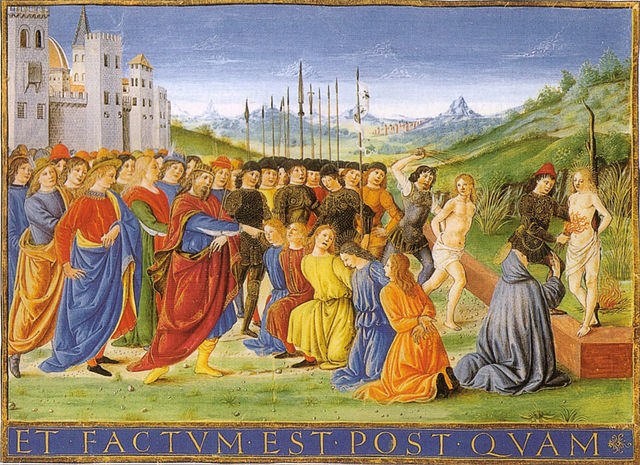

Just as the author of the Book of Zechariah looked for fulfilment of prophecies in his own day so did the author of the Book of Daniel and the chaotic times of Antiochus IV Epiphanes — armed struggle, persecution, temple defilement — supplied much material to fuel imaginations for this sort of thing. The events of 165/4 and the Maccabean revolt changed the way that unique passage in Isaiah 53 came to be interpreted by many. New ideas about the glorification of martyrs and even the ability of the blood of martyr heroes to take the place of atoning sacrifices entered the world of Judaism and its various sects. The Greeks had long held comparable ideas about human sacrifice and suffering. From the archaic period we encounter in Greek literature the pharmakos motif (see also the EB article). Many of us are aware of the sacrifice of the virgin Iphigenia bringing about the favour of the gods on the eve of the Trojan War. We see a new stage of heroizing fallen warriors with the Persian Wars. Those who died for their city-state and its holy laws came to be glorified as martyr saviours of their people. The closest to anything like these practices and cultural attitudes in the Old Testament are the stories of Jephthah’s daughter, Samson and the song of Deborah. The Old Testament condemned the child sacrifice of neighbouring Canaanites and Phoenicians. Those who died died because of their own sin — that was the dominant message in the OT. Prophets were slain but their deaths were not glorified or studied in any great detail as we might expect among their Greek counterparts. The Maccabean revolt changed everything.

In the three men in the fiery furnace in Daniel 3, we encounter for the first time Jewish martyrs who “disobeyed the king’s command and yielded up their bodies rather than serve and worship any god except their own God” (Dan. 3:28 Aramaic). [It is significant that the three young men do not die but are miraculously saved.] The accompanying Prayer of Azariah included in the Greek Additions to Daniel (between Dan. 3:23 and 3:24 MT) provides a theological comment . . . . (Hengel with Bailey, pp. 93-94)

From the Prayer of Azariah in some Bible’s today:

Such may our sacrifice be in your sight today [sc. like burnt offerings of rams, etc.], and may we unreservedly follow you, for no shame will come to those who trust in you. (Pr. Azar. 3:17, NRSV)

But an older Septuagint manuscript of the prayer (Papyrus 967) has a different middle line:

So let our sacrifice be in your sight today [sc. like burnt offerings of rams, etc.), and may it make atonement before [lit., behind] you, for there is no shame to those who trust in you, and may it be perfect before [lit., behind] you.

Martin Hengel, or rather the redactor of his article, Daniel P. Bailey, acknowledges uncertainties in the exact translation of the manuscript but there is no doubt that there is some linkage between the martyrdom of the saints and atonement. It is that emerging association that is seen as the significant step in theological evolution.

After Daniel we have 1 Maccabees written soon after the revolt. Those who died for the sake of God’s commandments are portrayed as glorious heroes. It is not until 2 Maccabees that we find the martyrs’ deaths being cautiously associated with sacrificial atonement.

2 Maccabees 7:37-38

I, like my brothers, give up body and life for the laws of our ancestors, appealing to God to show mercy soon to our nation … and through me and my brothers to bring to an end the wrath of the Almighty that has justly fallen on our whole nation.

In the next post I’ll detail the links between Isaiah and Daniel that may have pointed the way to this association.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Hello

I am sure I read somewhere on this blog a comment by Tim widow field that there were Jewish secs which thought that God was all powerful and he didn’t require animal sacrifices for forgiveness.

You can find heated debates on the subject by Googling for “animal sacrifice” and “Essenes”. It isn’t clear whether sects that decried temple sacrifices ever did so because they were against it on principle or simply because the current regime in Jerusalem was corrupt, making all their sacrifices there tainted and unacceptable to God.

In any case, during the temple’s hiatus in the Babylonian “captivity” and post-70 CE until now, there has to be some way to remove sins. Similarly, and sect that rejected the priesthood in the first century had to come up with an alternative. And so, for example, it appears that Philo thought the Essenes made other kinds of spiritual sacrifices as a substitute.

“. . . they have shown themselves especially devout in the service of God, not by offering sacrifices of animals, but by resolving to sanctify their minds.”