Oh, I shouldn’t have . . .

I gave myself Bart Ehrman’s new textbook, The Bible: A Historical and Literary Introduction, for Christmas. Here it is March, and I’m finally getting the chance to read it. I expect this overpriced volume has a pretty good chance of becoming the standard text in American undergraduate survey courses on the Bible. So it makes sense to find out what young students will be learning.

When I say young students, I mean the young ones sufficiently well off to be able to live on campus. As education costs here in the U.S. skyrocket, more and more first- and second-year university students are working at night and driving to junior colleges each morning. But this book speaks directly to first-year students living in dormitories. The audience is more likely Footlights College Oxbridge than Scumbag College.

Well done, Footlights! 10 points.

At the end of each chapter, Bart asks the posh kids living in dorms to “Take a Stand” on a few issues. Here’s a typical “Take a Stand” item:

Your roommate has not taken the class, but he is interested in the history of ancient Israel. He knows something (a little bit) about the time of the United Monarchy and asks which king you think was better, David or Solomon. What is your view, and how do you back it up? Give him way more information than he wants to know. (p. 112)

Which king was better? That’s a toughie. But not as tough as the questions on University Challenge.

[youtube:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ysG96dUtGh4]

Fortunately, when reading the core of the text, I can almost forget I’m reading a book targeted more at Lord Snot and Miss Money-Sterling than Mike, Rick, Vyvyan, and Neil. Unfortunately, it’s hard to overlook the mistakes I’ve found already in the early chapters.

I sweat the small stuff

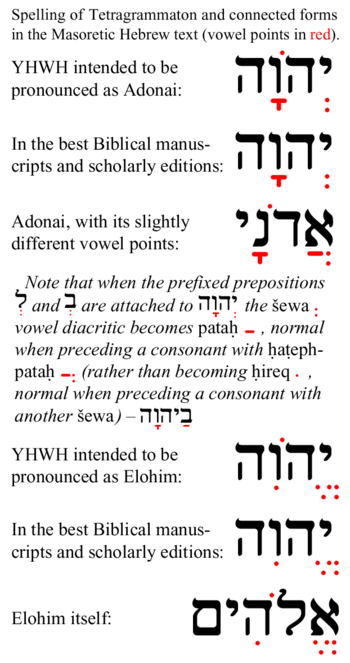

It may seem inconsequential, and maybe things like this shouldn’t bother me. But I can’t help myself. On the spelling of the Hebrew word for God’s name, Ehrman writes:

Because God himself was thought to be holy, it eventually came to be considered improper, or even blasphemous, to call him by his personal name. And so, when the ancient Jews read the Scriptures out loud, and came to the tetragrammaton [YHWH], instead of pronouncing it they would say, instead [sic], the word Adonai, the Hebrew word for “Lord.” That is why, even today, English translations as a rule do not give the personal name of God as Yahweh when it occurs — as it does thousands of times in the Hebrew Bible — but instead translate it as LORD (with capital letters, to differentiate it from the translation of Adonai as “Lord”). (p. 49)

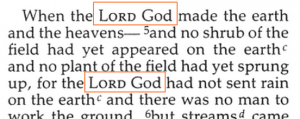

First of all, while it’s true that a few translations use all caps for “Lord” (especially in e-books and online) when referring to YHWH, it’s much more common for them to use small caps — Lord — rather than “LORD.” For example, in this image from the NIV, we see YHWH Elohim translated as Lord God.

“Lord God” in Genesis 2:4b-5 (NIV)

The initial large capital “L” retains the notion that we’re actually reading a proper name. So in this case, the Hebrew text would have the word YHWH, with vowel points that indicate the reader should say aloud, “Adonai.” But what would happen if the original text had “Adonai YHWH,” which is very common, for example, in the books of the prophets?

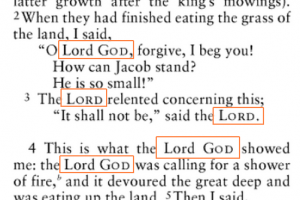

(New Oxford Annotated Bible)

Here we see what at first might look like a confusing hodgepodge. Sometimes God is in small caps with a preceding “Lord.” Other times, as in verse 3, Lord is in small caps. The rule is fairly simple: If the original Hebrew was written as “Adonai YHWH” (literally, “Lord Yahweh”), then the Masoretic vowel points around YHWH will indicate that it should be pronounced as “Elohim.” That is, rather than saying “Lord Lord,” they would say “Lord God.” In the case of the Oxford Bible, we know that any time we see a word in small caps (either God or Lord), YHWH is in the original text.

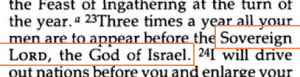

The NIV takes a different approach when YHWH comes directly before or after Adonai. For example, Exodus 34:23 ends with “pənê hā’āḏōn Yahweh ’ĕlōhê yiśrā’êl,” which the KJV translates as “before the Lord God, the God of Israel.” However, the NIV uses the word “Sovereign” to refer to “Lord (hā’āḏōn),” followed by Lord, and then “God.”

So when you see “Sovereign” in the NIV, you know that the actual word behind it is the Hebrew word for “Lord,” not YHWH. Unfortunately, we lose the flavor of the underlying spoken text for YHWH, which would be Elohim and not Adonai. On the other hand, the NIV gains consistency in that every occurrence of YHWH is written “Lord.”

Lost in translation?

We should note, though, that the NIV is a rare case. How rare? Well, I drew up a table that shows how YHWH is translated in Exodus 34:23.

| English Translation | God | Lord | Lord | Jehovah | Sovereign |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Standard Version (ASV, WEB) | x | ||||

| Authorized Version (KJV, NKJV, etc.) | x | ||||

| Common English Bible | x | ||||

| Darby Translation | x | ||||

| Douay-Rheims | x | ||||

| English Standard Version | x | ||||

| New American Standard Bible | x | ||||

| New English Translation | x | ||||

| New International Version | x | ||||

| Revised Standard Version (RSV, NRSV, etc.) | x |

As you can see, English translations follow different standards. By and large, though, when the Hebrew text contains YHWH, the English translation will have Lord in small caps. On some occasions a translation will give the reader a hint that YHWH would be pronounced “Elohim” by writing God in small caps. The latter practice is the norm for the KJV and most of its descendants.

In any case, Ehrman’s excursus on the tetragrammaton is misleading. Here’s what he got wrong so far:

- The ancient Hebrews did not always say “Adonai” when reading YHWH. Sometimes they said “Elohim,” so as not to say “Adonai Adonai.”

- Very few English translations of the Bible write “LORD” in all caps. It’s much more common for them to use Lord in small caps.

- Several translations don’t always use Lord for every occurrence of YHWH. When Adonai comes directly before or after YHWH they write God instead.

As we said above, the vowel points added by the Masoretes signaled to the reader how YHWH should be pronounced aloud. Ehrman writes:

But in order to make sure that ancient readers of the biblical texts did not inadvertently say the name Yahweh when they came to it, they provided it with the vowels that went instead with the word Adonai. This combination of consonants and vowels was very difficult to pronounce, and so readers would be alerted to the divine name, and would simply speak it as “Adonai.” (p. 49, emphasis mine)

Are we supposed to imagine readers of Hebrew “sounding out” words phonetically as they scanned the text and thinking, “Wow, that’s hard to pronounce“? It is inconceivable that anyone at the time who was sufficiently fluent in Hebrew to be able to read it would not immediately recognize the divine name — יהוה — with or without the vowel points. Further, they would know not only that the name of God should never be uttered, but that its true pronunciation had been lost centuries ago.

Ehrman’s difficulty-in-pronunciation theory is absurd. What the reader actually thought was this: “Here is the divine name. What word do I say instead? Let’s look at the vowel points.” And then he would say the alternate word associated with those vowels.

[Note: The practice of using vowels to indicate a pronunciation that is not reflected in the original consonantal spelling of the Hebrew word is called qere. See the inset to the right for more details.]

Ehrman concludes:

It was this strange conglomeration of consonants and vowels — keeping the consonants of the tetragrammaton but using the vowels of the word “Adonai” — that led to the invention of a new word in English: “Jehovah” (since JHVH is the English equivalent of YHWH). (p. 49, emphasis mine)

That’s incorrect. The English equivalent of YHWH is YHWH. The letters “JHVH” are a Latinization of יהוה (YHWH), which appeared at least as early as the 1278. A Spanish Dominican monk named Raymundus Martini translated a quotation from Bereshith Rabbah, in which God asks Adam, “And what is my name?” To which Adam replies:

יהוה Jehova, sive Adonay, quia Dominus es omnium.

[“Jehova, or Adonay, because thou art Lord of all.”]

It also appeared in Latin as Yehova. The article by George Moore quotes the Codex Majoricanus and Codex Barcinonensis:

“Cum gloriosus nomen de cunctis Dei nominibus, videlicet Yehova, vel Yod, He, Vau, He: vel nomen quatuor literarum.”

[“With the most glorious of all the names for God, namely Yehova, or Yod, He, Vau, He: or the name of four letters [i.e., the tetragrammaton]]

(see American Journal of Theology, Vol. 12, p. 35, bold emphasis mine)

The word Jehovah, then, showed up first in Latin texts and eventually made its way into German and English. Referring back to the article in the American Journal of Theology, we see that Martin Luther referred to the name “Jehovah” as the equivalent of “HERR” (LORD).

It is noteworthy that this passage occurs, not only in an academic lecture or a commentary addressed to the learned, but in a sermon, immediately published as a popular pamphlet. The name Jehovah is not introduced as something new; on the contrary, it is used as if it was familiar to the hearers or readers. (pp. 40-41)

You could argue that these are all small points, but Ehrman’s book is, after all, a textbook for university students. If it doesn’t matter whether we get things right here, then when does it matter?

Bigger problems: They still don’t read Wellhausen

In the same chapter (viz., Chapter 2: The Book of Genesis), while describing the Documentary Hypothesis (DH), Ehrman writes:

Julius Wellhausen . . . managed to convince an entire host of fellow scholars of [the Documentary Hypothesis’s] persuasiveness, starting with his major 1878 publication (in German), History of Ancient Israel [sic]. (p. 50)

That statement is incorrect. It doesn’t help the student much to refer to the name of a book that did not exist in English translation. Wellhausen did indeed publish a work called Geschichte Israels (“History of Israel,” not “History of Ancient Israel“) in 1878. However, the book was republished in 1882 with the more familiar title, Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels. It was this version that Black and Menzies translated into English in 1885, and is thus more commonly known to us as Prolegomena to the History of Israel.

Worse than getting the title wrong, Ehrman perpetuates a persistent myth about the sources with respect to the name of the deity. Specifically:

It is called E because it prefers the name Elohim (= “God”) for the deity. (p. 51, emphasis mine)

And:

This priestly source, like E, prefers the name Elohim for the deity but uses a number of other names (such as El Shaddai, as we saw in Exodus 6:2-3). (p. 51, emphasis mine)

I can’t help but wonder where this misconception originally came from, because it’s so common, yet so far from what Wellhausen (or any DH scholar, for that matter) actually said. Wellhausen, explaining the difference between the Jehovist and Elohist documents writes:

Of what remains, the parts most easily distinguished belong to the so-called “main stock” (“Grundschrift”), formerly also called the Elohistic document, on account of the use it makes of the divine name Elohim up to the time of Moses . . . (p. 7)

And with reference to the Priestly author Wellhausen writes:

[H]e even goes so far as to avoid the name of Jehovah even in his own narrative of the pre-Mosaic period. Even when speaking in his own person, he says Elohim, not Jehovah, down to Exodus vi. (p. 311)

It makes no sense to say E or P “preferred” the name Elohim. After all, the law code in P is full of references to Yahweh. We read that the people should do this or not do that, “for I am Yahweh.” What’s important is the unique turning point in history when God appears to Moses in Exodus and reveals his true name, an event that has great significance in E and P. For the Elohist and Priestly writers, the revelation of the divine name occurs when God intervenes in history and establishes a special bond (a covenant) between himself and Israel.

The authors of E and P did not prefer Elohim. They simply wrote it in place of the divine name until the true, preferred, name was revealed. Moreover, saying that E and P used a different name for God misses the point entirely. Quoting Richard Elliott Friedman in The Bible with Sources Revealed:

This line of evidence is frequently described as a matter of terminology: namely, that different sources use different names for God. But that is not correct. The point is not that sources have different names of God. The point is that the different sources have a different idea of when the name YHWH was first revealed to humans. (p. 25, emphasis mine)

Misunderstanding the true significance of the usage of the divine name in the Pentateuch can lead to errors such as the common mistake concerning Genesis 7:1.

7:1 And Abram was ninety years and nine years old, and YHWH appeared to Abram and said to him, “I am El Shadday. Walk before me and be unblemished,

7:2 and let me place my covenant between me and you, and I’ll make you very, very numerous.” (translation by Richard Elliott Friedman)

If you “knew” that P preferred Elohim or El plus an epithet (e.g., El Elyon, El Shadday), then the mention of Yahweh could look as if it violates the rule. But it doesn’t. The narrator and the implied reader know that God’s name is YHWH, but he is revealing himself to Abram as El Shadday. As Friedman puts it (in The Bible with Sources Revealed):

Those who misunderstand the matter of the name of God in the sources mistakenly think that the mention of God’s name, YHWH, in v. 1 is an exception to the hypothesis. This verse is precisely the point. The issue is not that the sources use different names for God. It is that the sources have different ideas of when God’s name was revealed to human beings. (p. 56)

Conclusion

In a series of blog posts on Reza Aslan’s book Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, Ehrman rightly took the author to task on a raft of errors, both historical and New-Testament-related, concluding with:

Well, that’s enough to give the idea. Again, these may seem like unimportant matters to some readers. Still, others may feel as I do, that even though anyone on the planet is, of course, free to write a book about Jesus, they should not do so claiming either explicitly or implicitly to be an authority if they are going to make basic mistakes on the very sources that stand at the center of their investigation. (emphasis mine)

Responding to blog readers who attempted to excuse Aslan as a non-expert in the field, Bart said that observation “was both obvious and unfortunate.” Similarly, one could argue that Ehrman is a New Testament scholar, and not really an expert in the OT. On the other hand it’s highly unlikely that Aslan’s work will become the core textbook for any Historical Jesus course at any university. Yet we can be quite sure that The Bible will be a best-seller for years to come.

Aslan’s book will pass out of the public’s attention rather quickly, but Bart’s book, with its “basic mistakes on the very sources that stand at the center” will affect (or afflict) a generation of students. And while “anyone on the planet is free to write a book” on the Bible, only a handful of respected scholars will get the backing of Oxford University Press.

Later in the Aslan series Ehrman writes:

Someone who is not an expert makes mistakes – lots of mistakes, and often serious mistakes. And the problem is that the person doesn’t even know it. I don’t think Aslan knowingly wrote anything he didn’t think. The problem is that he doesn’t know the field well enough to know where there are gaps in his knowledge, or where he has accepted incorrect information that he has heard or read one place or another.

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Tim,

I found your explanation of various translations of YHWH to be fascinating. Thanks.

But I did find your ridicule of Ehrman bit laborious — perhaps your intended audience is actually your buddies who love jabs at Ehrman and not us normal folks. This excessive nitpicking severely distracts from your helpful insights and corrections to folks like me. But again, it seems your intended audience is in-house folks.

This excessiveness is no more clear than when you quote Ehrman and put a “sic” for his duplicate use of “instead”, I wonder — “Really, is Tim trying to get me to totally ignore his may points. He seems most interested in just pickiness.” I see mistakes in all sort of great writing.

Heck, I loved this post but I found a few possible mistakes:

“Well, I drew up a table that shows how is [sic] YHWH translated in Exodus 34:23”

“By and large, though, when the Hebrew text contains YHWH, the English translation with[sic] have Lord in small caps.”

Or where you spelled the Oxbridge Posh word “excursus” with an “i” — or perhaps that is a British spelling.

Your pointing out Ehrman’s jab at Aslan is a good point- and you are giving it back to him, though it feels like you could have done it with a little less drama — but that is me.

Instead, what would be cool to do is make a separate blog called, “ Mistakes in Ehrman’s “The Bible”. Do very succinct (not bitter) corrections in each SHORT post. Then, I imagine University teachers (Christian and non-Christians alike) would reference the blog when they assign the book. That way, you could reach many folks outside your inner circle. This is great stuff, I’d like to see it reach more.

Now, for a question:

Concerning YWHW -> JHVH,

I was confused.

Wouldn’t the correct vowels make:

YWHW —> YawHey (yahweh)

whereas if Adonai vowels were used:

YWHW —> YeHoWa —>Jehovah

or something like that. The “Y” to “J” issue is immaterial in the argument — it was the vowels that were important.

I know NO Hebrew, so that part of the explanation was hard for me to understand.

Sabio:

1. It’s always a tricky business tagging any quote with “sic.” Maybe I should just quit using it altogether. I actually added it late in the writing process, while reading it aloud. I thought I had made a mistake in copying the text, went back, and realized that the two “insteads” were really there.

But your point is well taken. The reader can infer more than “It appeared this way in the text”; it can sound like “Oooh! Look what I found!”

2. Thank you for the corrections. I’m pretty good at proofreading other people’s writing, but when I proofread my own stuff, my brain tends to auto-correct while I’m reading it.

3. As far as maintaining a list of errata for Ehrman’s The Bible, I’m not convinced of its utility. These people do not take kindly to corrections from the peanut gallery. And I’ve found that even the most gently worded suggestion that a scholar is wrong will be interpreted as hostile and mean-spirited.

As far as “drama” goes, you may have a point. However, when you read has much of this stuff as I have, you tend to get fed up when scholars play the credential card.

4. To your questions:

Actually, it’s YHWH. Technically, there are no “correct vowels,” because saying the divine name aloud became taboo very early on. Presumably, during the First Temple period the high priest, at least, knew the original pronunciation. And centuries before that, uttering the name probably wasn’t prohibited, since there are so many theophoric names that contain the divine name or parts of it — for example, Elijah (Eliyahu).

The puzzle of how to pronounce the word is compounded by the fact that well before the vowel points were invented, Hebrew had adopted the concept of using existing consonants as vowel indicators. For example, when the “H” (“he”) appears at the end of a word, it is silent, but indicates a vowel sound. When you read names like Isaiah, Judah, Jeremiah, etc. That’s what you’re seeing.

In fact you can see this practice in the spelling of “Jehovah.” The final “H” is what we call a matres lectionis. The question would be whether the first “H” should be pronounced as a consonant, starting a syllable, or as a vowel indicator, ending a syllable.

The reconstructed “Yahweh” presumes that the first “H” ends the first syllable — YaH.

Again, I presume that’s a typo, but you’re essentially correct. A Jewish reader of Hebrew would never attempt to read the YHWH aloud, because it’s forbidden. So what we’re dealing with is the fact that non-Hebrew readers may have been unaware of the practice of qere, and tried to pronounce YHWH with the vowels for Adonai.

However, to be fair, when the Masoretes added the vowels to YHWH, they didn’t put a note in the margin, which was apparently the normal practice for qere. See page 43 of the Moore article for a discussion of how the error occurred and was propagated.

I’m not sure if I answered you question, so let me know if anything isn’t clear here.

Hey Tim,

Thank you for taking my comments so well. I totally sympathize with your anger at snobby scholars.

Concerning Yahweh (YHWH):

Interesting, and though still over my head, that helped a bit.

You quote Ehrman as saying: “but using the vowels of the word “Adonai” — that led to the invention of a new word in English: “Jehovah” (since JHVH is the English equivalent of YHWH).”

Leaving out the parenthetic in this statement, isn’t it essentially right?

When YHWH is pronounced with the vowels of Adonai, the resultant word (whatever that is) is one that take very little to then transform into Jehovah. (Ignoring the Y->J issue)

Is there a way to follow comments by e-mail?

Sabio: “Thank you for taking my comments so well.”

I like it when people offer corrections for what I’ve written. Please don’t stop!

Sabio wrote: “Leaving out the parenthetic in this statement, isn’t it essentially right?”

I don’t think so. The invention occurred in Latin and was borrowed into German and then English. Recall as well that Ehrman is not just wrong about “J” being the English equivalent of “Y,” but he also wrong in his implication that “YHWH” became “JHWH” when English readers misunderstood how to pronounce the tetragrammaton. That is not what happened.

I’ll say it again: “You could argue that these are all small points, but Ehrman’s book is, after all, a textbook for university students. If it doesn’t matter whether we get things right here, then when does it matter?”

Bart’s HuffPo article in 2012 for Did Jesus Exist was my first introduction to an actual debate about whether Jesus existed or not. But even I knew at the time that his arguments in that short piece were shoddy. Looking into Bart’s work more closely, I found something that shocked me at how brazenly apologetic an atheist NT scholar could be.

Reading about his NT textbook, Bart said he put the Gospels before the Epistles because he wanted the students to know something about Jesus before they read what Paul had to say about him. Unbelievable! So while I can respect he has done some great individual works of scholarship, I would never trust him in general any farther than I could throw him.

That article led me to Vridar and the great writing you and Neil do, as well as a good commenting section. Thanks all, including Bart!

You never know where that “nudge” will come from. For me, it was reading Freke and Gandy’s The Jesus Mysteries. I knew at the time it wasn’t a good book, but it made me go look everything up that I thought I knew. It was that process that made me realize I needed to re-evaluate the major theories and the evidence behind them. That’s probably worth a post of its own.

Neil, why do you always make Bart Ehrman look like a klutz? ;^)

No reply necessary, thanks!

Yeah, Neil. Explain yourself.

Well I know you were being facetious, but actually Bart’s ignorance about how YHWH was to be pronounced by the reader in Synagogue really made my head hurt and my brain explode! I knew that even from my University days and I was a civil engineering student. I got my factual information about the two pronunciations from, of all sources, that fundamentalist crank by the name of Herbert W. Armstrong!

That aside, the Moffat Version of the Bible has “Eternal” for the tetragrammatron and HWA popularised this on his radio program. Personally, I prefer “Lord-Eternal” and “Eternal-God” for the alternate pronunciations, in small-caps of course.

Funny you should mention that. I was reading Jean Astruc’s Conjectures over the weekend, and noticed that in the French translation of the verses in Genesis 2, he used “l’Eternel Dieu” for “YHWH Elohim.” For example,

I remember listening to “The World Tomorrow” with Garner Ted Armstrong back in the ’70s. When I heard the Firesign Theatre’s Everything You Know Is Wrong the first time I was blown away by the near-perfect voice impression.

“There’s a seeker born every minute!”

Didn’t Bart Ehrman slam Thomas Thompson for daring to speak on the New Testament, when Thompson was an *Old* Testament scholar?

And yet Bart appears to think that a New Testament scholar like himself is quite qualified to write on the Old Testament?

I would assume the defense here would be that Ehrman’s book is only putting the conventional story about the Old Testament into a textbook form, while Thompson was proposing something unconventional about the New Testament when he wasn’t an expert on it. Since Ehrman isn’t doing anything novel, but just packaging up conventional analysis for a student population, he doesn’t need to be a specialist.

That said, it was still stupid – point out the factual mistakes being made. If factual mistakes aren’t being made then it isn’t a lack of expertise that is at issue it’s something else (i.e. that he’s deviating from the accepted interpretation of the facts) and argue against that. Accusations of “this person is not an expert” are only useful if you THEN go on to point out places where their lack of expertise has led to critical mistakes in their argument because their lack of expertise has led them to argue from mistaken premises. If you can’t do that then shut up about their expertise and address why their analysis is mistaken. If you can’t do that, explain what the accepted analysis is and explain why it’s a superior model that provides better explanatory power for the facts. And if you can’t do that then you are most likely wrong and you need to seriously consider the idea that the other person’s analysis is better than the conventional wisdom whether or not you like it.

In an ideal world, a scholar would recognize his or her weaknesses and do a little extra research. And before publishing a book, our ideal scholar would ask real experts to look at it. The mistakes I’m finding are in keeping with the superficial understanding of the Hebrew Bible and Judaism that people focused on the NT often make.

You might wonder why the publisher would ask Bart to write a textbook on the entire Bible. It’s fairly simple: Bible Buffs Buy Bart’s Books. McGrath recently showed a marketing sticker that showed how “cheap” the book is compared to the competition.

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/exploringourmatrix/2013/12/bart-ehrman-the-bible-a-historical-and-literary-introduction.html

So, yeah, it’s “product,” and the price-point and the author’s recognizable name ensure that the publisher will move that product. Oxford University Press is going to sell truckloads of ’em!

Jer: Accusations of “this person is not an expert” are only useful if you THEN go on to point out places where their lack of expertise has led to critical mistakes in their argument because their lack of expertise has led them to argue from mistaken premises.

Ehrman’s criticisms of Aslan were mostly spot on. Some of the mistakes were just weird. You wonder how they got published in the first place. Don’t forget — many journalists who take their jobs seriously are capable of writing decent works on subjects they’re initially unfamiliar with. They do research. They ask the experts. They write, rewrite, and rewrite again.

These are skills any reasonably intelligent person can learn and master, but it takes a certain amount of humility to put them into practice. I believe it was Zindler who said he was dismayed that despite having given books to Ehrman and making himself available for questions and clarifications, Bart never contacted him.

The problem doesn’t arise from a lack of competence, but rather from a surfeit of vanity — not ignorance, but arrogance.

I have noticed that most scientists don’t have this attitude that, because they were experts 10 years ago and have taught the thing for years since, they now know it all. I have asked several PH.D.s this week, with research in string theory or cosmology, whether they understand the latest discoveries about gravitational waves from unimaginably early in the universe printing patterns of differing polarisation on the cosmic microwave background radiation and so providing evidence for the theory of inflation. They all say, without shame, no I do not understand it – I must study and read about it when I have the time. Like monks who just keep tolling the bell Biblical historians go on about the apocalyptic prophet or other Jesus they have taught for years, use the outdated criteria, and despise any thought of checking their facts or rethinking their ideas. Perhaps the effort they have put into their existing teaching notes feels to them like proof that any other approach is contemptible. I suppose other historians will eventually look at the rational arguments and move to a new consensus, leaving the biblical historians behind.

We have Casey’s condescending view of scientists as opposed to theologians on page 28 of his book:

Bart Ehrman’s research is amazing.

Did you know that the Gospel of Mark is our earliest account of the trial and crucifixion of Jesus?

http://www.salon.com/2014/03/23/did_jesus_think_he_was_god_new_insights_on_jesus_own_self_image/

‘According to our earliest account, Jesus was dead in six hours…..’

Doesn’t the Gospel of Mark (our earliest account) portray Jesus as calming a storm – something only a god can do?

isn’t that an early source?

I quote Bart ‘As I pointed out, we have numerous earlier sources for the historical Jesus: a few comments in Paul (including several quotations from Jesus’s teachings), Mark, Q, M, and L, not to mention the finished Gospels of Matthew and Luke.’

Seems like Mark is an early source (along with Q,M and L and Matthew and Luke – 6 other early sources!)

Wrong!

The Gospel of Mark is late, not early.

‘Instead, they may be traditions assigned to Jesus by later storytellers in order to heighten his eminence and significance. Recall one of the main points of this chapter: many traditions in the Gospels do not derive from the life of the historical Jesus but represent embellishments made by storytellers who were trying to convert people by convincing them of Jesus’s superiority and to instruct those who were converted. These traditions of Jesus’s eminence cannot pass the criterion of dissimilarity and are very likely later pious expansions ‘

‘Our earliest account’ is full of ‘later pious expansions’.

All these history students going to university under the naive impression that the same document can’t be both early and late. Bart will learn them!