I’ve been preoccupied with catching up with what certain New Testament scholars have writing about the way ancient Greek and Roman authors wrote history and the relevance this has for how we interpret Acts and the Gospels and what they can tell us about Christian origins. This all started after I began reading and posting on some works from the Acts Seminar. One work has led to another and back again and I think I’m ready to resume.

I’ve been preoccupied with catching up with what certain New Testament scholars have writing about the way ancient Greek and Roman authors wrote history and the relevance this has for how we interpret Acts and the Gospels and what they can tell us about Christian origins. This all started after I began reading and posting on some works from the Acts Seminar. One work has led to another and back again and I think I’m ready to resume.

In an earlier post I quoted something written by Dr Todd Penner that encapsulated a conclusion I have been persuaded to reach not only about one episode in Acts but about the entirety of Acts also about the Gospels:

There is nothing in Acts 7 to suggest that there lies behind them anything but an adept ancient writer, someone extremely well-versed in Jewish traditions and styles of rewriting the biblical story.

The narrative portions of Acts 6:1-8:3 leave one with the same impression.

Could the narrative portions be historically accurate and true? Absolutely. Could they be completely fabricated? Absolutely. Could the truth rest somewhere in between? Absolutely.

The problem, of course, is that it is impossible to prove any of these premises.

Attempts by Hengel and others to intuit their way behind the stories aside, the unit is too tightly knit to allow one to go beyond what is given in the narrative itself. If the dominant view in Acts scholarship is that one can separate out the core historical events from the Lukan redaction, this study argues for the futility of such attempts. (In Praise of Christian Origins, pp. 331-332, my formatting and bolding)

Dr Penner covers a lot of ground, surveying ancient commentaries on what made for good and bad writing of historia/history. I cannot cover any of that in this post. What is particularly significant about his argument, for me, is the assumptions and logic he brings to his reading of Acts. He takes readers back through a time tunnel to show them the origin of modern scholarly assumptions that Acts is fundamentally (beneath all its fantastical tales of miracles and romantic adventures) based on historical sources. If we read “beneath” the text then we will begin to glimpse genuine historical data related to Christian origins.

In so doing he leaves the alert reader with the awareness that the a priori assumption of historicity cannot be justified. At the same time, being able to explain narrative details in terms of literary artifice does not mean that they are not also, at some level, based on genuine historical events. What we are left with, however, is an explanation that does work and that can be justified (the creative literary one), and the question of historicity left hanging. Readers who approach Acts with Christian faith need not be alarmed.

As I read Penner’s arguments I wondered if he would be prepared to apply his same pertinent critical questions to the Gospels. As far as I can see there is no reason to confine his approach to Acts.

Not yet, but scholars like Thomas L. Thompson, Neils Peter Lemche, Philip Davies have demonstrated the literary (non-historical) character of much of the Old Testament, and a few have now published similar arguments about Acts. Surely, eventually, the methods applied in these instances will have to catch up one day with our analysis of the Gospels.

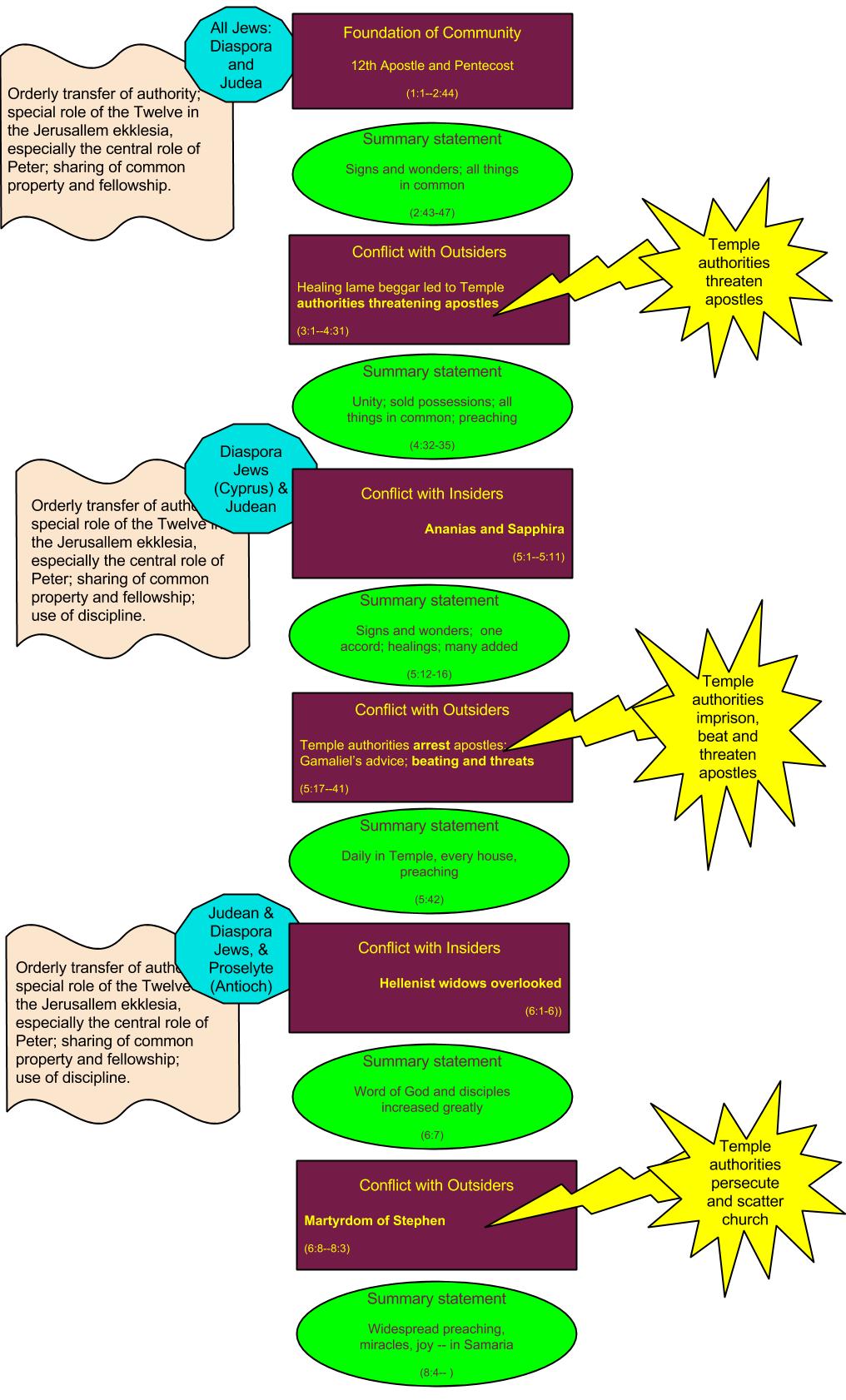

As I was reading Penner’s In Praise of Christian Origins I was imagining illustrative diagrams that would capture some of the multilayered complexity of the author’s literary creativity. I’ve added the result below.

What the author is doing is demonstrating

- the way the early community met challenges both external and internal, and how the community resolved each one according to both Greek/Roman and Biblical ideals of the day: these ideals included concern for the poor (Barnabas from Cyprus selling possessions) and widowed (alms to all), and for integration of diverse peoples in civil harmony (as evidenced in other historical writings)

- the way the new ‘political body’ handled the sorts of issues that always arise in new communities (self-serving dissidents; equitable management and judgments soon being too much for the original leadership): these being resolved by the exercise of authority to wield divinely sanctioned discipline; the orderly transfer and sharing of authority as epitomized by Moses (Exod 18, Num 11, Deut 1)

- the way the new politeia handled relations with its brethren Temple community: the Temple community falling into passionate excesses and violence while the new community, their brethren, demonstrating self-control and dignity

- the gradual expansion of the gospel to include all nations, as prophesied/commanded by Jesus: the “ingathering” of Jews not only in Judea but Jews from all nations at Pentecost, and then also the gentiles being included as the gospel went first to Jerusalem and then to Samaria, with the first reaches to non-Jews coming from Greek-speaking Jews (Hellenists — to be argued in another post) and a proselyte from Antioch

Once we can see that these are the themes the author is weaving together in an effort to demonstrate the praiseworthy origins of the Church — praiseworthy by both pagan (Greek and Roman) and biblical (Jewish) standards — we have a starting point for understanding the nature, purpose, and even sources of the narrative.

The original recipients of the gospel, and the way others are gradually included, is a literary and theological construct. It is based on divine prophecies, not only from Jesus’ mouth but also from Isaiah. The original authority governing the church and the way this is expanded is also a literary and ideological construct, based upon the way Moses nobly passed on the same powers to others. The way the original assembly grew strong by resolving crises from both without and within demonstrated its noble character. Its successes in the face of both external and internal threats demonstrated its evident approval by God and all mankind.

Often scholars have bypassed all of this literary and theological creativity in order to focus on what religious sub-group the Hellenists must have been. I cannot discuss any of that in depth here. The point here is to see that the Hellenists are most likely simply Greek-speaking Jews and are as much a literary and ideological construct as are Ananias and Sapphira and their foil, Barnabas of Cyprus; or as much a necessary part of the history as the angels opening the gates of the prison holding apostles who had performed a great miracle in the name of Jesus.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

2 thoughts on “Acts 1-7 as Creative Literature, not History — Illustrated”