Introduction

I’ll begin this post by acknowledging my debt to Earl Doherty. It was he who convinced me that the gospel Paul believed and preached was derived only from scripture and visions/revelations, and that it did not include a Son of God who lived a human life on earth. Doherty’s demonstration of those points in his The Jesus Puzzle and Jesus: Neither God Nor Man is, in my opinion, quite persuasive. And since some of his arguments for those contentions are available on Vridar (See part 19 of: Earl Doherty’s response to Bart Ehrman’s ‘Did Jesus Exist?’), I see no need to argue them further here. For this post I take as my point of departure that Paul did not believe in a Son of God who had wandered about Galilee and Judaea teaching and preaching, exorcizing demons, working miracles, and gathering disciples.

What the Son did do, according to Paul, was descend from heaven, get crucified by the rulers of the world (1 Cor. 2:8), and then rise back to his celestial home. But where did he believe the Son’s crucifixion had occurred? And what was his belief regarding how that event procured salvation for the faithful? And was there a particular scripture that led him to his core beliefs about the Son?

But where did he believe the Son’s crucifixion had occurred?

And what was his belief regarding how that event procured salvation for the faithful?

And was there a particular scripture that led him to his core beliefs about the Son?

.

My answers to these three questions are different from Doherty’s. He proposes that the crucifixion was believed to have taken place in “an unspecified spiritual dimension,” in a “dimension beyond earth,” or perhaps somewhere above the earth but below the moon (Jesus: Neither God Nor Man, p. 112). But I think it was believed to have taken place in Judaea. I see the Son’s descent for crucifixion as being a limited particular task like those performed by disguised divine personages and angels who descended to earth in other Old Testament and intertestamental literature, e.g., the incognito visit by heavenly figures to Abraham and Lot; the angel Raphael’s incognito mission in Tobit.

In regard to Paul’s soteriology, Doherty holds that at least the seven so-called undisputed Pauline letters were largely the work of one man, and so he apparently finds ways to explain to his own satisfaction the presence of varying soteriological teaching in them. I, on the other hand, have a serious problem with their inconsistences and think, as I have explained in posts two through six, that they have been heavily interpolated. And so in the letters I would disentangle the rescue and redemption soteriology of Simon/Paul from the sacrifice and atonement soteriology of a proto-orthodox interpolator.

Finally, Doherty, as a prominent part of his argument for locating the Son’s crucifixion in a sublunary heaven, has recourse to the Vision of Isaiah, i.e., chapters 6 – 11 of the Ascension of Isaiah (see pp. 119 – 126 of Jesus: Neither God Nor Man). I too think the Vision of Isaiah is key for understanding Christian origins. In fact, I go further and argue that it—in its original version—was already in existence by 30 CE and was—more than any other writing—the source of Simon/Paul’s gospel. But I am not convinced that it located the Son’s crucifixion somewhere other than Judaea.

| In this post and the next I am going to discuss the possibility that Simon/Paul derived his gospel initially from the Vision of Isaiah and that in its original form it possessed a Son of God who descended to Judaea for only a few hours.I suspect the Vision depicted a Son who, having repeatedly transfigured himself to descend undetected through the lower heavens, transfigured himself again upon arrival on earth so as to look like a man. Then, by means of yet another transfiguration, he surreptitiously switched places with a Jewish rebel who was being led away for crucifixion. All this was done by the Son in order to trick the rulers of this world into wrongfully killing him. |

.

Preliminaries

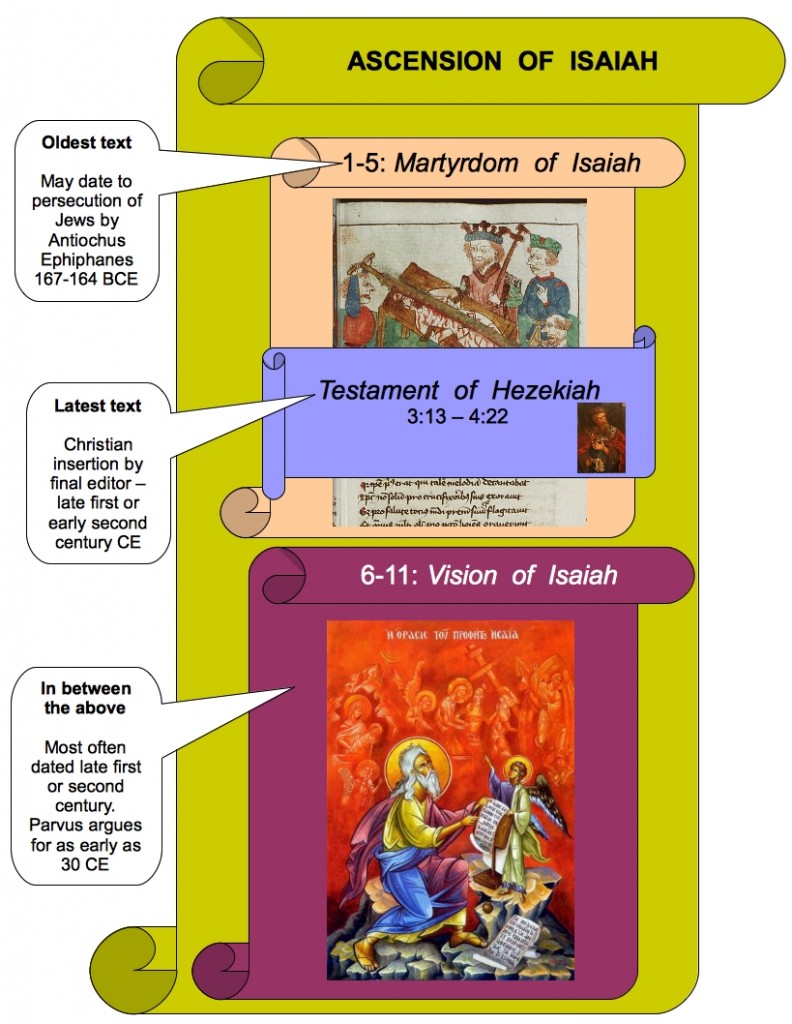

The Ascension of Isaiah is a composite work made up of at least two parts.

- The first, which consists of chapters 1-5, is usually referred to as the Martyrdom of Isaiah.

- The second, the Vision of Isaiah, consists of the remaining chapters and is known to have circulated independently.

The Martyrdom section itself is, in the opinion of many scholars, a composite work. It is thought that its oldest element (the story of Isaiah’s murder) is Jewish and that 3:13-4:22 is a Christian addition to it. Whoever made the insertion, however, did so with an awareness of the Vision, for “3:13 clearly alludes to chapters 6-11, and there are also a number of other links between 3:13-4:22 and the Vision” (M.A. Knibb, “Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah: A New Translation and Introduction,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by J.H. Charlesworth, p. 148). Finally, besides these three larger sections there are some short passages that may be the redactional work of the final editor who put the Ascension together.

Chronologically the Jewish source of the Martyrdom would be the earliest component of the Ascension, and may go back “ultimately to the period of the persecution of the Jews by Antiochus Epiphanes in 167-164 BC.” (Knibb. P. 149).

The latest component would be the 3:13-4:22 interpolation and, if it is also the work of the final redactor, probably dates sometime from the end of first century CE to the first decades of the second.

Continue reading “A Simonian Origin for Christianity, Part 7: The Source of Simon/Paul’s Gospel”