Continuing the series on Thomas Brodie’s Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery, archived here. Continuing the series on Thomas Brodie’s Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery, archived here.

This post begins with the final section of Brodie’s book, Part V, Glimmers of Shadowed Reality: Some steps towards clarifying Christianity’s origin and meaning.

|

In this final section Thomas Brodie attempts to offer an explanation for Christian origins without an historical Jesus. He then shares his own reflections on what it means to be a Christian and to abide in a deep faith in God even though he no longer believes Jesus walked this earth. For Brodie, Jesus becomes a profound symbolic expression of the nature and character of God.

Chapter 18, “Backgrounds of Christianity: Religions, Empires, and Judaism”

Brodie opens with a panoramic sweep of the worlds major religions and laments that in all cases we are left without answers to the questions of exactly how and through whom they originated.

Nonetheless, Brodie finds cause for some optimism from our ability at least to know something of the world from which Christianity emerged. So he covers here the usual story of ancient empires — Persian, Hellenistic, Roman — and the way they led to the concept of a universal imperial peace and more effective bonds of communication, culture, language, law, and so forth.

Add to this the diversity of Judaism and even the chaotic disunity of the Jews politically, culturally and geographically, and the catastrophic consequences of the Jewish War of 66-73 CE.

The destroying of the temple meant that for Judaism the institutional centre was not merely in trouble; it was gone, and with it the traditional priesthood — a numbing moment for many, but for others a time to build something new. (p. 181)

And so we have many Jews eventually falling in with rabbinical traditions — with new writings coming to form the Mishnah and eventually the Talmud, while some others followed a new way of a new Joshua (=Jesus) . . . .

Chapter 19, Christian Origins: Writing As One Key

Not that Brodie sees the fall of Jerusalem and destruction of the Temple as catalysts for the birth of Christianity. Critical though the events of 70 CE were, Brodie believes that the letters of Paul are sure evidence that

a role should also be given to the inspirations and divisions that existed within Judaism prior to 70 CE. (p. 182)

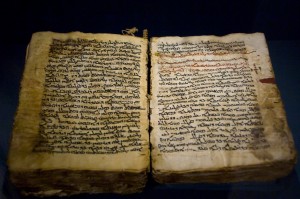

Brodie suggests that Christianity’s gestation will be found to be closely associated with a well developed process of writing from its beginning. He brackets this possibility with a similarly critical role for writing in other major historical events, such as the Magna Carta, the Reformation, the US Constitution, the Communist Manifesto, and so forth.

But what is certain is that, while the Jewish people became known as the People of the Book, the Christians became de facto the primary developers of the codex, the bound book which replaced scrolls, and which, whatever its origin, emerged energetically about the same time as Christianity. (p. 182)

The bottom line for Brodie is that coordinated writing played a significant part in Christianity’s origin. To support his claim he addresses six points. Continue reading “Making of a Mythicist, Act 5, Scene 1 (Explaining Christian Origins Without Jesus)”