This post attempts to build on my two recent posts about classicist John Moles’ discussion of the meaning and power of the name “Jesus” in the earliest Christian literature through reflections on a Hymn in Paul’s letters that seems impossible for most scholars to accept at face value.

I’ve made positive use of two of Alan F. Segal‘s major publications (Two Powers in Heaven and Paul the Convert) so when I saw his chapter on the resurrection in The Resurrection of Jesus (compiled/edited by Robert B. Stewart) I was not expecting what I in fact found there in his discussion of the Philippian Hymn — Phil. 2:5-11. Segal begins admirably but within a few lines he suddenly does a complete flip flop and it is difficult to understand how certain explications he offers have anything to do with the Hymn at all.

Being able to read the Hymn for what it is takes on a special significance if one goes along with widespread scholarly opinion that it had an independent and liturgical life before Paul added it to his letter, and that Paul’s own writings well preceded the Gospels. In other words, it is possibly one of the earliest clearly Christian writings that we know about.

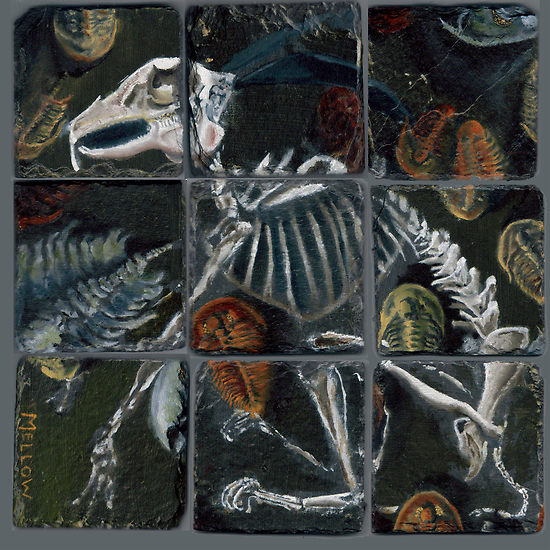

I suspect that the Hymn (read without Gospel presuppositions) is exactly the sort of fossil that the rest of the evidence tells us to expect at this earliest strata of evidence. But the way it is interpreted by many biblical scholars actually makes it look like a precambrian rabbit.

What one observes across the New Testament epistles, Gospels and Acts is a general trajectory from a very high Christology to an increasingly humanized Jesus. The epistles (written before the Gospels) speak of a divine Christ figure worshipped alongside God. The Gospel of Mark gives us a Jesus who is the Holy One of God with power over all demonic forces and the forces of nature and by the time we read Luke and Acts we are reading about a Jesus who weeps and whose death has no greater significance than that of another human martyr. Given this trajectory from divine to increasingly human, with its implication that Christianity from its earliest days worked to steadily develop a more humanized Jesus, one would expect to find anything preceding the epistles will contain a Jesus with precious little humanity about him.

When Segal begins his discussion of the Philippian Hymn he sounds like he is about to demonstrate just this:

Paul’s famous description of Christ’s experience of humility and obedience in Philippians 2:5-11 also hints that the identification of Jesus with the image of God was reenacted in the church in a liturgical mode:

Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus,

who, though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited,but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.And being found in human form,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.Therefore God also highly exalted him

and gave him the name

that is above every name,so that at the name of Jesus

every knee should bend,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,and every tongue should confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father. (Phil. 2:5-11)This passage has several hymnic features that lead scholars to believe that Paul is quoting a fragment of primitive liturgy or referring to a liturgical setting. Thus, Philippians 2 may easily be the earliest writing in the Pauline corpus as well as the earliest Christology of the New Testament; it is not surprising it is the most exalted Christology.

In Philippians 2:6, the identification of Jesus with the form of God implies his preexistence. The Christ is depicted as an eternal aspect of divinity that was not proud of its high station but consented to take on the shape of a man and suffer the fate of men, even the death of a Christ (though many scholars see this phrase as a Pauline addition to the original hymn). (pp. 125-6, my bolding)

(And yes, that bit about death by means of the cross breaks the symmetry and is suspect to some.)

What Segal says here is exactly what we read in the hymn. The one who was known as “Christ Jesus” was equal with God and took on the likeness of a human form.

But then in the next sentence he loses any reader who knows only the Hymn:

This transformation from divinity to earthly human is followed by the converse, the retransformation of the man Jesus back into God.

I can match the words in the Hymn “in human likeness” and “in human form” to Segal’s “taking on the shape of a man”. But Segal was clearly using these words as a window into future texts that would not be written for decades: the Gospels with their earthly human Jesus.

But there is yet hope, for Segal continues with another salient detail in the Hymn:

Because of his obedience, God exalted him and bestowed on him “the name that is above every name” (Phil. 2:9).

And that name, if I continue to read the hymn, is surely the name “Jesus”:

and gave him the name

that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus

every knee should bend . . . .

Segal reads this, but he cannot see it. He searches for another name nowhere found in the Hymn and that contradicts the clear thought-flow expressed in the Hymn:

For a Jew (and Paul remained a Jew his whole life), this phrase can only mean that Jesus received the divine name, the tetragrammaton, YHWH, understood as the Greek name kyrios, or Lord. Sharing in the divine name is a frequent motif of early Jewish apocalypticism where the principal angelic mediator of God is or carries the name Yahweh, as Exodus 23 describes the angel of Yahweh.

This is difficult to accept given that the Hymn only speaks of “Lord” as a title, rank or position and not as a personal name at all:

so that at the name of Jesus

every knee should bend,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,and every tongue should confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord . . .

The “Lord” is identified as a ruler over heaven and earth and every tongue — this is a rank, not a personal name. The personal name of that Lord before whom all will bow is Jesus. That is the name above all names that was given this divine being.

Now Jesus was a very common name among Jews of the first century. So it is understandable that Segal and many others should balk at what those words seem to (and do!) say. But Segal’s explanation simply does not fit. It is an attempt to fit a round peg into a square hole and just does not quite work. The Hymn says that the name bestowed as a reward for submitting to the “form or likeness of a man” was “Jesus” and that this Jesus was Lord, not named “Lord”.

Now we have also seen that that common human name of Jesus happened to take on some very uncommon attributes in the early Christian literature as explained by classicist John Moles in my two recent posts. To Greeks the name signifies “saving healer” and is a name to be worshipped as the epitome that stands in direct overpowering opposition to all the forces of illness, uncleanness, demonic powers and death in the world.

Though the name may be common in its earthly setting, in its cultic context those who wrote about it treated it as anything but common. Those authors used a range of literary devices to structure it into their narratives and maxims as a name that had the power to save even from death and was worthy of worship.

The literary fossil evidence pertaining to the function of this name in early Christian worship informs us that the earliest chronological strata saw the name as belonging to a heavenly being as a reward for taking on the likeness of a human and becoming obedient to the point of death. Later strata, according to some, introduces death by means of a cross. Eventually we find Gospels, in particular the Synoptics, depicting a Jesus as an earthly human and over time more human traits are introduced while some of the divine significances of his death are stripped away.

What Segal and many other scholars like him are trying (needing) to see is the theological equivalent of a precambrian rabbit.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Philo, a contemporary of Paul, didn’t see the word “lord” as a name but as a title:

Questions and Answers In Genesis (51)

Why is he said to have built an altar to God, and not to the Lord? In passages of beneficence and regeneration, as at the creation of the world, the sacred writer only refers to the beneficent virtue of the Creator, by which he makes everything in its integrity, and he implies this by concealing the royal title of Lord, as one which bears with it supreme authority; therefore now also, since what he is describing is the beginning of the renewed generation of mankind, he borrows for his description the beneficent virtue, which bears the title of God; for he used the kingly attribute, which declares his imperial power, by which he is called Lord, when he was describing the punishment inflicted by the flood.

(57) Why God places a cherubim in front of the Paradise, and a flaming sword, which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life? The name cherubim designates the two original virtues which belong to the Deity, namely, his creative and his royal virtues. The one of which has the title of God, the other, or the royal virtue, that of Lord

In “Epistle to the Philippians: a commentary on the Greek text” by Peter Thomas O’Brien (parts viewable in Google Books), O’Brien points out (p 237) that in v9 ‘name’ is “not used simply of an individual designation as a proper name”. The phrase ‘[name] above every [other] name’ “shows that something additional is in view”. He points to Isaiah 42:8: ‘I am the Lord, that is my name’. So that is ‘the name above every name’, in his view.

… that name, if I continue to read the hymn, is surely the name “Jesus”

It makes more sense to me that the name is “Lord”.

In my previous comments, I have argued that young Christians created short fictions — gospels — about Jesus Christ descending to Earth and interacting with human beings there. I have compared this genre to modern “fan-fiction”.

The creation, performance and sharing of short hymns about Jesus Christ define a different genre, but the enthusiasm, innovation and artistry are similar in both genres.

I think that Peter, the very first Christian, meditated on the story about wandering Hebrews in the Sinai Desert who had been bit by poisonous snakes being healed when they looked at a bronze statue of a snake, attached to a pole that was held high.

Exactly how did this purification work? When a poisonous snake bit a person, a demon moved from the snake into the person. Then, if the person looked at the bronze snake, the demon was fooled into leaving the person and going toward the bronze snake. After all, the demon had come from a lowly snake on the ground and so would be attracted to an apparently elevated, supernatural snake, which was a decoy attracting the snake demon.

So, what if a person were polluted not by a snake, but rather by sins committed by fellow human beings? The polluted person contained a demon that likewise might be fooled by the sight of an elevated, supernatural human being. The fooled demon would leave the polluted person and go toward that decoy.

So, Peter climbed to the top of Mount Hermon, where he meditated intensely, and eventually he saw his mystical vision of a supernatural human-being hanging from high pole (eventually a tree and then a cross) on the Firmament, and Peter’s own internal demons flew out of him toward the decoy, and so Peter was purified.

Peter told others about his experience, and eventually he coached some others into climbing with him to the top of Mount Hermon, and he coached them into seeing the same mystical vision that he had seen. Peter did this for many years, perhaps for decades, and slowly he acquired some followers.

Gradually, the vision became elaborated. The supernatural person hanging on the pole had been a deity who had descended from the higher heavens. After he had served as a demon decoy for a while, he ascended back up into the heavens. But before he ascended, he died and was buried for a while. Then he arose from the grave, and only then did he ascend. And then a meal was added to the story, so prove that he was a real human being, not just a spirit. And so forth and so on.

So, the story was elaborated, but essentially the story still took place entirely on the Firmament, the story began with the crucifixion and ended with the ascension, and there never was any interaction between 1) the deity on the cross and 2) the human beings on Mount Hermon who were mystically perceiving the story. The deity did not preach or talk to the human beings. Watching the vision was like watching a silent film. The purpose of watching the vision was to be purified from internal demons, not to be taught wise ideas.

Anyway, some of Peter’s followers developed this experience into subsequent artistic expression. For example, they created and performed hymns for each other about the experience. This hymn in Paul’s letter to the Philippians might be such a song, which originated from that very early period and from Peter’s first followers.

The theme of this song is that Jesus Christ was a deity who had agreed to serve as a slave for a while. Essentially, he hung himself from a pole on the Firmament, serving as a dumb decoy for demons of a particular kind who had occupied human beings who had mystical visions of this kind. This slavish task was so damaging to Jesus Christ, that he eventually died for a while, But then God the Father resurrected him and allowed him to ascend back up into the heavens.

Apparently, this hymn recounted the mystical experience in a manner that was acceptable to Peter and the other first leaders and also in a manner that was artistically pleasing for everyone who performed or heard the hymn. And so the hymn survived among later Christians until it eventually was heard by Paul, who included its words in this letter.

The gospel stories were a genre that developed long after the first Christian hymns. The gospel stories were developed by young Christians who had joined the religion after the original experience of climbing to the top of Mount Hermon to see the mystical vision had been terminated. But, the gospel stories continued the tradition of creating hymns and stories in an artistic manner.

Creating and sharing gospel stories — fictions about Jesus Christ descending to Earth and interacting with human beings — were a new fad. This was like young people today writing fan-fiction elaborating about popular movies and novels.

After watching the movie Dirty Dancing, some people write and share their own sequel stories about how the main characters might have continued their relationships, eventually getting married and raising their children to become professional dancers.

Likewise, after hearing about Jesus Christ slavishly hanging on a pole in the Firmament, some young Christians created stories about this Jesus Christ then descending to Earth and interacting with human beings — healing them, consoling them, teaching them.

I think also that in this hymn the phrase “emptied himself” indicates that the demon flew from the polluted person into the Jesus Christ hanging on the pole. The latter had to empty himself beforehand in order to make room for all the demons that would fly into him. Eventually all the demons killed him, and so he was taken down from the cross and buried. In this process, the demons perished too, during the course of three days of the burial. Then Jesus Christ was able to rise from the grave and ascend back up into the Heavens.

Hi! I wasn’t aware that you are using my Precambrian Rabbit painting until now. Please include a link under the image with my name: “© Glendon Mellow” and link to http://glendonmellow.com . Thank you!

Very pleased to acknowledge it as requested. I regret I have no idea how the image came to my attention in the first place. Awesome art!

Hi Neil,

your comment re precambrian rabbit raised a chuckle [yes I have only just become aware of this humorous remark in science / evolution/ religion debates…

your comment characterising a generally declining christology raised an eyebrow as the gospels end with John chronologically

Regards

Thank you Neil, much appreciated.