When I wrote a series of posts on resonances between the Argonautica by Apollonius of Rhodes and several features of Old Testament narratives, I confessed I did not know how to understand or interpret the data. But someone else does. Philippe Wajdenbaum in 2008 defended his anthropology doctoral thesis, “Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible.” He applies the structural analysis of myths as developed by Claude Lévi-Strauss to the Bible, something Lévi-Strauss himself never got around to doing, although he did eventually encourage biblical scholars to do so. This post looks at one detail of a detail-rich article in the 2010 Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament (Vol. 24, No. 1, 129-142), “Is the Bible a Platonic Book?” (After a few more posts on this my next project will be to see if the same type of analysis can be used to suggest origins of the Gospel myths.)

Lévi-Strauss and structural analysis of myths

In Wajdenbaum’s words,

For Lévi-Strauss, a version of a myth is always derived from an existing adaptation, originating most of the time from a different culture and language. A myth must always be analysed in comparison to its variants within the same cultural area where contacts between populations are proven. (p. 131)

Wajdenbaum is analysing the Bible narratives as myths (though he concedes they may contain some historical elements), and comparing the accounts with narratives and laws from Greek literature. While Ancient Near Eastern literature offers many laws similar to those in the Bible, he thinks the Greek literature has not been explored in this context to its full potential. (I am already wondering about the Gospel narratives, and the relationship between Jewish and Greek mythical and literary culture in this context.)

For Lévi-Strauss, similarities between myths that may appear as coincidental at first look must be investigated more deeply. This investigation may ultimately reveal that the analysed narratives are actually variants of the same myth. In Les Mythologiques, Lévi-Strauss builds a very strong case for this argument in his analysis of Native American myths. The story of “The bird nester” can be found in hundreds of different variants in every part of both South and North America — proving that the same initial story spread itself through millennia of oral diffusion. . . .

Lévi-Strauss describes how that the order of the episodes of a myth can be reversed from one variant to other and that many motifs can be inverted. . . .

Lévi-Strauss sought to discover universal rules of transformation in all myths, similar to the discovery of universal principles in structural linguistics and phonology. The aim of Lévi-Strauss was to show

that mankind thinks everywhere the same; that there is no objective distinction between so-called “primitive” and “civilised” thoughts.

Parallelism is not a dirty word. Like the proverbial hammer that cares not whether it is used to build a house or bash the skull of a prisoner, analysing parallels can serve valid and good and invalid and bad functions.

Parallelisms must not be analysed in an isolated way, but one must try to find out the possible narrative structure that links the similarities together. In other words, the similarity . . . is not sufficient by itself to speculate about any possible borrowing. . . . we must examine the place and role of these in their own contexts. . . .

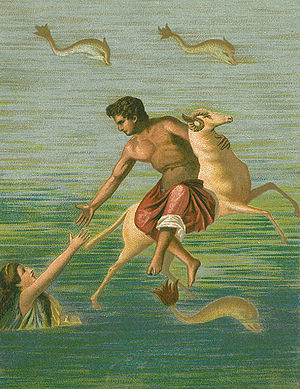

Phrixus and Isaac

So with the context of the methods of Lévi-Strauss in mind, no-one will jump to the conclusion that the well-known parallelism between the Greek myth of Phrixus and the binding of Isaac indicates a source-derivative relationship. What will be needed, after examining the parallels, is an examination “of the place and role of these stories in their own contexts”. That step will probably have to wait for the next post.

Here is the Phrixus myth in, hopefully, a quick easy to read ladder, with a crucial key noted in step ten.

- Athamas, king of Boeotia, married Nephele, a cloud goddess created in the image of Hera by Zeus.

- Athamas and Nephele had twin children: a son, Phrixus, and a daughter, Helle.

- Athamas afterwards rejected Nephele and married Ino.

- Ino hated her stepchildren, Phrixus and Helle, so plotted to have them killed by their own father.

- Ino bribed messengers who told king Athamas that the oracle of Delphi (speaking for the god Apollo) required the sacrifice of Phrixus on Mount Laphystion in order to end a famine in Boeotia.

- Just as Athamas was about to sacrifice his son Phrixus, Zeus (or Nephele in other versions) sent a golden-winged ram to rescue Phrixus and Helle by flying away with them.

- Helle fell off, hence the Hellespont (Helle’s sea).

- The ram brought Phrixus safely to Colchis (Georgia).

- In gratitude Phrixus sacrificed to Zeus the golden ram that saved him, and hung its golden fleece on an oak tree.

- Now, while it may seem quite inconsequential, probably the most important ingredient of this myth is that it is “the prologue of the epic of the Argonauts, who will come to Colchis years later to bring the famous Golden Fleece back to Greece.” The significance of this will become apparent in my next post where I begin to compare the structural contexts of this myth and the binding of Isaac.

We can recognize the resemblance to the binding of Isaac in Genesis 22.

- To test the faith of Abraham God orders him to sacrifice his only beloved son on Mount Moriah.

- Abraham submits to the command and binds his son.

- At the last moment God sends an angel and interrupts the sacrifice.

- Abraham sees a ram stuck in a bush, and sacrifices that ram instead of his son.

But note the inversion “of one small detail”:

In the Greek version, the ram is killed first; then its fleece is hung in a tree. Whereas in the biblical version, the ram is first stuck in a bush and sacrificed afterwards. This inversion of detail can lead us to wonder whether these stories could both derive from a common source; one could derive from the other; or that the resemblance is only due to a coincidence. Therefore we must examine the place and role of these stories in their own contexts, respectively the epic of the Argonauts and the biblical narrative. (p. 132)

That will be the subject of the next post on Wajdenbaum’s SJOT article.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I think both stories come from a common historical practice. There apparently was a period when the practice of sacrificing valuables to the gods sometimes included the sacrifices of one’s own children. Eventually, however, the moral disapprovals of sacrificing one’s own children ended that element of the practice.

Ancient stories provide traces of that remembered evolution in the practice of sacrificing to the gods. The stories express horror about the sacrificing of one’s own children. And some of the stories include an element which expressed the idea that the sacrifice of some major animal (e.g. a ram) was a sufficient alternative.

In other words, similar elements in these varied stories of scattered peoples rather simply reflect a real memory of a real, common, ancient experience — the occasional and eventually rejected sacrifice of one’s own children. The experience really happened in the real memory of real, scattered peoples, and that is the simple reason why similar traces can be found in scattered, ancient stories.

The reason to think there is possibly more to the Phrixus and Isaac stories than comparative historical memory is the presence in both of that detail of a ram that (1) saves; (2) is sacrificed; (3) is caught in a thicket/tree; (4) is the prologue of a story about divine promises of a new land for a chosen people being fulfilled.

Those first three elements are part of a free-floating collection that can be restructured to create new, but related, narratives. The fact that the elements are independent of the particular cultural narratives is demonstrated by the way they can be reversed in order in the different stories.

This indicates, I think, something other than similar but contingent historical memories of repudiation of human sacrifice.

If the original story said that God did not intervene, thus permitting Abraham to kill Isaac, who was immediately resurrected, then was the sacrifice technically made without need for a ram or a thicket? That is, could the edited story (a later, Yahwistic redaction which keeps Isaac in one piece) have borrowed from the Phrixus myth at a later time?

From Mythology and Among the Hebrews and Its Historical Development (Goldziher and Martineau) p. 47:

“…and behind this stage we find the original form of the myth: ‘Abram kills his son Isaac.’

At that primitive stage these expressions naturally signified no more than the words imply.”

I wonder on what grounds it is (was) understood that that is the original form.

Goldziher believed that in the earliest form of the myth Abram (Abh Ram, the “Lofty Father”) killed his son Isaac (Yischak, the “Laughter”). He writes, “The Nightly Heaven and the Sun, or the Sunset, child of the Night, fell into strife in the evening, the result of which is that the Lofty Father kills his child; the day must give way to the night.”

But what convinced some later commentators to conclude that Isaac died in the original story was Gen. 22:19. “So Abraham returned unto his young men, and they rose up and went together to Beersheba; and Abraham dwelt at Beersheba.” We are told that Abraham and Isaac climbed the mountain together, but Abraham walked down alone.

Goldziher is still sitting in my bookshelves unread. Was there then no resurrection of Isaac in the original story? When/how did daylight resume?

Goldziher says Isaac simply reappears. “The slain Isaac appears again on the arena a few hours after he was killed; he shows himself afresh.”

In the early mythical stage, the sun that reappears in the morning is absolutely identical to the sun that died yesterday at sunset, “though substantially it is a different one from that which fell dead to the earth…”

There’s a similarity in this “reappearing” motif with the midrashic stories of Isaac being sent to Eden after his death and reappearing on stage as needed, descending from heaven/paradise. Some Rabbis said that’s why Rebecca fell off her camel.