One of the most common arguments I read and hear for the historicity of any part of the Gospel narratives is: The church would have had no reason to make it up.

When I first encountered this remark I assumed it was just a passing phrase and that the real argument would soon follow. But it never did. It took me some time to grasp that even leading scholars (I could understand apologists) regularly relied on this mantra to completely close the question on any point of historicity.

I had never heard the argument used as a proof of anything in my university studies. I only encountered for the first time in a serious context when I began to study mainstream biblical (in particular New Testament and Jesus) scholarship.

Not surprising, I suppose. Most of those in the field of biblical studies have probably relied on this fallacious reasoning in other contexts through much of their lives — like their belief in God in the first place. As for the atheists in the field, maybe they are just being intellectually lazy.

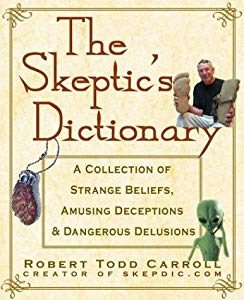

Compare the following from The Skeptic’s Dictionary

divine fallacy (argument from incredulity)

The divine fallacy, or the argument from incredulity, is a species of non sequitur reasoning which goes something like this: I can’t figure this out, so God must have done it. Or, This is amazing; therefore, God did it. Or, I can’t think of any other explanation; therefore, God did it. Or, this is just too weird; so, God is behind it.

This fallacy is also a variation of the alien fallacy: I can’t figure this out, so aliens must have done it. Or, This is amazing; therefore, aliens did it. Or, I can’t think of any other explanation; therefore, aliens did it. Or, this is just too weird; so, aliens are behind it.

Another variation of the fallacy goes something like this: I can’t figure this out, so paranormal forces must have done it. Or, This is amazing; therefore, paranormal forces did it. Or, I can’t think of any other explanation; therefore, paranormal forces did it. Or, this is just too weird; so, paranormal forces are behind it.

This is merely a circular assertion of one’s starting assumption. Is it used as the reason to establish “a fact” in any scholarly discipline apart from biblical studies?

Of course when alternative explanations are presented, those who had rested on this fallacy are able to do little more than scoff in disbelief at any alternative, just the way staunch believers in the paranormal will despise the “ignorance” of genuine rational explanations. Well, it is also called the fallacy of incredulity.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Surely if you understood what you studied, you know that the “divine fallacy” and the historical reasoning you are talking about are very different things. A historian doesn’t bring God into the picture. A historian does, however, legitimately conclude that, if something was embarrassing to a group, or seemed to be counterevidence to their claims or emphases, it is less likely that they invented it. Obviously, depending on the time frame and situation, it may be that someone else could have made it up, and it only became embarrassing or controversial with the passing of time.

But I’m sure historians would appreciate it if you didn’t misrepresent their reasoning by depicting it as though it is the same as something it isn’t.

James, as Steven explained in the post below, you have failed to grasp the point of my analogy.

But you hit on the heart of the fallacy here. Lack of imagination — almost wilful resistance to investigation once the unimaginative answer locks in. Maybe, just maybe, the so-called embarrassment is all the product of a “historian’s” assumptions. Maybe such oddities in the evidence are really indicators that the “historian” really has a bit more to learn about the actors involved. And as I’ve pointed out, the so-called ’embarrassments’ in the Gospels are over Mark’s own adoptionist or separationist christology.

Criterion of embarrassment may be able to tell us a few micro details through analysis of personal motives in a narration, but only in biblical studies, as far as I can tell, is it used as the sole determinant of what is or is not a substantive historical fact.

As for the “historians” you fear I am misrepresenting, do you mean exclusively “biblical historians” who do indeed rely on this criterion, or rely entirely on the unimaginative “I can’t see why it would have been made up”, as a determinant of historical facts? If so, I retract nothing. They are following the same logic (albeit with different labels) as found in the divine fallacy.

If you find “the divine fallacy” discomforting, then think of the alternative label I also supplied: “argument from incredulity”.

Neil never claimed that ‘historians bring God into the picture’.

He just pointed out the analogy of claiming that something must be true, because somebody can’t think why it was made up to ‘Or, I can’t think of any other explanation; therefore, God did it.’

And the argument from embarrassment falls on its face when applied to the Gospels.

The church was supposed to have had decades to rewrite any embarrassing facts about Jesus, before Mark wrote his Novel.

So how did embarrassing things survive this process of rewriting for decades before ‘Mark’ ‘recorded’ them?

Unless ‘historians’ want to claim that these facts were so embarrassing to the church that for decades they did nothing whatever about putting a spin on them….

And only when ‘Mark’ wrote them down, did the church suddenly decide that they really ought to do something about these stories to make them more acceptable.

In fact, the criterion of embarrassment pretty much guarantees that anything in Mark that is embarrassing cannot be historical.

If the process of spin started when the story first hit the light of day, then the story first hit the light of day when Mark wrote his Novel.

If the process of spin did not start when Mark wrote his Novel, then it couldn’t have been embarrassing.

Either it was embarrassing from the start or it wasn’t.

So Mark was either the start, or it was not embarrassing.

So the criterion of embarrassment is useless.

Obviously, depending on the time frame and situation, it may be that someone else could have made it up, and it only became embarrassing or controversial with the passing of time.

And that’s exactly the situation we have in the gospels. The embarrassment is all the embarrassment of the adapters/redactors of the Markan narrative toward its elements. Baptism by John? No embarrassment in Mark. The embarrassment is all on the part of the authors of Matthew, Luke, and John especially. Jesus’s behavior at Gethsemane? The embarrassment is the author of Luke, who thought that his superhuman savior figure shouldn’t express doubt and despair. The empty tomb? The embarrassment and apologetic rewriting is all found in the author of Matthew’s treatment of his source material.

There are many other major and minor examples, but the thing to note in all these episodes is how self-consciously literary and/or symbolic these episodes are in Mark. The fear of the women at the empty tomb, and their flight in terrified silence, even the very fact that the only “witnesses” are women: under the presumption that a “historical core” lies at the heart of the narrative, the unreliability of the “witness” and the troubling ambiguity of the episode suggest transmission of stories a Christian would be ‘less likely to invent.’ But on the ordinary assumption that literary productions oriented toward symbolism and allegory are unlikely to have been intended to transmit history, period, it seems so obvious to me that in the Markan empty tomb pericope we are ineluctably in a literary world, where no interrogation of the “witnesses'” reliability is expected or implied. Do we ask whether Ishmael is telling us the truth when we read Moby Dick? Or do we read it as a literary narrative the world of which we must “enter” and that we must rely on from that view to tell us what it means to convey? Would our approach be any different if we only knew Moby Dick as an anonymously authored text of uncertain provenance?

There are many things which are unlikely to be made up. A few: Why would Mark be so particular as to identify Sabbath times by describing ‘evening, at sundown’ (a detail lost on Matt and Luke) if he wasn’t writing for a pre Christian Jewish audience? There are several examples where Mark assumes his audience know Jewish law but it doesn’t seem plausible that a myth writer would make it up – or even know Jewish law well enough to invent it. Crossley Date of Mark has detailed discussion of this. Also, why would Matthew concede ‘some doubted’ that Jesus was risen if some didn’t, and why would a myth writer make it up? Why would he make up occasions when Jesus was wrong? For example, the temple prediction of it being destroyed stone by stone when it was later actually burned, the prediction that Jacob and John would die with him, (drink from the cup metaphor) And why isn’t it til John that Jesus becomes God? Mark only calls him the messiah, and his Jesus never claim that title for himself. Earl Doherty start his introduction ‘someone wrote a story [Mark] about a man who was God’ – but Mark doesn’t! John does. Why does the author make up Jesus suffering in a very human way in Mark and not at all in Luke and John? I could go on but I wasn’t going to carry on procrastinating over blogs… There are many examples of tradition which has been made up, with later Christian interests but not those of a first century Jewish prophet.

STEPH

Also, why would Matthew concede ’some doubted’ that Jesus was risen if some didn’t, and why would a myth writer make it up?

CARR

Why would Matthew have to explain away the fact that nobody had heard of most of these alleged disciples?

Easy. He just claimed they were doubters. So that explains the fact that nobody had heard of these mythical people.

As for the claim that Jesus was wrong because the temple was burned by fire, when it was predicted it would be destroyed ‘stone by stone’, I can’t think of a single Christian who would agree that was a failed prophecy.

If it was embarrassing to Matthew, it would have been the work of a second to change this alleged prophecy.

That is what religious people do. They change facts to suit their agenda. So if Matthew did not change it, then we know it suited his agenda. So it was not embarrassing to him.

STEPH

Why does the author make up Jesus suffering in a very human way in Mark and not at all in Luke and John?

CARR

Because Mark has a Jesus who was a human being and made the Son of God at the baptism?

I find it astonishing, literally mind-blowing, that these are the best arguments that can be mustered.

I am pleased that Steph has produced some arguments, but can’t understand how anybody can think they are any good.

STEPH

Why would Mark be so particular as to identify Sabbath times by describing ‘evening, at sundown’ (a detail lost on Matt and Luke) if he wasn’t writing for a pre Christian Jewish audience?

CARR

Merely corroborative detail, intended to give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative….

Something happened because somebody noted the time that it happened???

Can you imagine a non-Biblical historian using such an argument?

I mean, can you even begin to imagine reading such an argument in a book about Julius Caesar or Ned Ludd?

stevie – I don’t have to critique Casey’s monographs here, I just cite him where I agree. And frankly your flat denials are unconvincing.

So Stephanie doesn’t bother to produce a non-Biblical historian who uses the argument that something is historical because the author says what time of day it happened.

STEPH

And why isn’t it til John that Jesus becomes God?

CARR

How does that stop Mark being a Novel?

Stephanie has to find some actual real evidence that the characters in the Novels existed.

Where is the evidence for Judas, Thomas, Lazarus, Nicodemus, Joseph of Arimathea etc etc?

Where is any evidence that John the Baptist had anything whatever to do with Christianity, let alone baptise this Jesus?

What stops her recognising that ‘Mark’ is as much fantasy as the Infancy Gospels?

She must have an actual argument, other than that a later author than Mark decided to call Jesus God.

If you count the Mandean book of John as an external control for the story of John the Baptist, then there is at least evidence that John abolished the Mosaic law for his followers. That puts him in line with the basic philosophy of Christianity that the ceremonial elements of the Torah need not be followed, right?

Merely corroborative detail, intended to give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative

I don’t think so. It’s symbolic in some way or perhaps a formulaic means of building tension as the climax draws near. Two (not necessarily exclusive) explanations might be: 1. The author had in mind some liturgical use of his narrative, where the ‘time-cues’ in the Passion narrative actually indicate times of day when the work is read aloud as part of a proto-Easter liturgy, and, 2. one I’ve been musing on but isn’t really developed yet, viz, the author is self-consciously laying chronos on the kairos of the crucifixion and resurrection. He knows he’s innovating, he’s telling us, and not for the first, or for the last time, that he’s telling a story, that we’re in a literary world.

Carr and steph are both wrong here as far as I can tell. For one, I don’t think the author intended Mark to be “convincing” in the sense you mean, that it needed versimilitude really, but I certainly don’t see how the time-markers in the Passion narrative in Mark indicate historical accuracy or even historiographical intentions. And I’m not sure what the argument is attached to the fact that Luke and Matthew don’t include the element.

The moral of the story is, blogs are not the place for detailed discussion of text. Neither are Doherty and co who don’t engage with biblical languages in any comprehensive way.

A historian does, however, legitimately conclude that, if something was embarrassing to a group, or seemed to be counterevidence to their claims or emphases, it is less likely that they invented it.

Less likely than what Dr. McGrath? As I understand the argument, that is the problem with the lack of controls. One element of the story may be more likely based on fact than another element, but if we have no independent basis for determining that either one of them is historical, the comparative probability tells us nothing.

“And why isn’t it til John that Jesus becomes God?”

The curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. And when the centurion, who stood there in front of Jesus, heard his cry and saw how he died, he said, “Surely this man was the Son of God!”

But Jesus remained silent and gave no answer. Again the high priest asked him, “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed One?”

“I am,” said Jesus. “And you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Mighty One and coming on the clouds of heaven.”

Peter said to Jesus, “Rabbi, it is good for us to be here. Let us put up three shelters—one for you, one for Moses and one for Elijah.” (He did not know what to say, they were so frightened.)

Then a cloud appeared and enveloped them, and a voice came from the cloud: “This is my Son, whom I love. Listen to him!”

Yes, I can’t imagine anyone coming away from these texts and seeing Jesus as anything other than a mundane subversive carpenter’s son, exactly the description Mark seems to be portraying.

Brian – The double time marker (not in the passion but in Mark 1.32ish in a healing story) indicating the Sabbath was important to Mark to assure readers he was within Jewish law. Crossley has detailed discussion of other occasions where Mark assumes knowledge of Jewish law, details that would hardly concern a non Jewish myth writer or the early church. Neither would they invent wrong prophecies while Matthew and Luke have edited Mark to avoid Jesus being wrong. Neither was it in the church’s interest to admit any doubting disciples but while Matthew might have had to concede there were, Luke carefully missed it out. Mark was not trying to be ‘convincing’ – he was following tradition. But I haven’t even scratched the surface – Crossley (Date of Mark) and Casey engage far closely with the text and have laid out arguments with greater clarity and detail. For me it has always been about historical plausibility and while before I studied ancient literature (and languages) I thought it possible that Jesus was a fictional person who may or may not have been based on memory of a real person, I now think it extremely implausible that much of the gospel material was made up, and it is this material which fits a historically plausible first century Jewish prophet.

And Evan, for Mark, Jesus is the anointed son of God, not God.

“Crossley has detailed discussion of other occasions where Mark assumes knowledge of Jewish law, details that would hardly concern a non Jewish myth writer or the early church.”

There were no Jews in the ‘early church’? I’m not saying it was made up, but the argument that nobody in the ‘early church’ was qualified to know how to make this stuff up is pretty lame.

“Neither was it in the church’s interest to admit any doubting disciples”–What is the church? There was no monolithic church to begin with. It was in Marcion’s interest to make the disciples doubt so he could say only Paul understood the gospel. And it was in the Catholic interest to have the doubting disciples endowed with power from on high after the resurrection of Jesus to counter Marcion’s leaving them in doubt and replacing the whole lot of ’em with Paul.

In any case, I find it more likely that changes have been made to the original concept of the gospels than that Jesus is just made up. My beef is only with the assumption of some monolithic ‘early church’ that didn’t exist. There were doctrinal battles, huge ones, over things like whether Jesus was even born at all of descended from heaven already having his body, and if he was born was it from a virgin or not. The assumption of a monolithic ‘orthodox’ position early on is without foundation.

“Neither was it in the church’s interest to admit any doubting disciples but while Matthew might have had to concede there were, Luke carefully missed it out.”

Mark’s original ending left them in doubt. You say Matthew has them in doubt, and I’ll take your word on that. I know Marcion’s gospel left them in doubt, and it was a shorter Luke. Now the question is, which came first the chicken or the eggs? That is, Luke or Marcion’s gospel? If Marcion’s was first and canonical Luke is an enlargement of it, then the disciples were left in doubt in the urLukas (proto-Luke, whatever you want to call it) and the Catholics adding the whole endowing them with power and opening their understanding thing to remove this feature. If canonical Luke was first then Marcion took out the opening of their understanding and all thus making his ‘mutilated Luke’ line up better with Mark (and Matthew?). In any case, you are left unable to explain why some gospels leave the disciples in doubt while only Luke has their understanding opened at the end, that is if you rely on the traditional “monolithic orthodoxy came first” viewpoint you seem to be operating from. If you recognize the diversity of early Christianity, or better yet the monolithic heterodoxy (as viewed from later perspectives) of the first Christians, then it makes sense.

You obviously aren’t very familiar with the literature rey so it’s very difficult to know even where to start to explain.

Pardon me, Steph. I am operating under the assumption that a character who raises people from the dead, has God announce that he is his son, and has recognition from demons, centurions and others that he is the “son of God”, dies and has the curtain of the temple rend at his death, and then is resurrected as he has been foretelling he would be throughout his story is semi-divine at the very least. Perhaps if one of your family members began to announce that they were the anointed son of God you would find nothing peculiar about it, but most people would pull out the Haldol.

Is it your belief that a semi-divine being is somehow not divine?

In a Jewish context Evan, son of God is not an expression of divinity. For the tearing of Temple curtain, as symbolic of God rending his garments, see Roger Aus who has collated many such examples from Jewish literature. If you want I’ll find the reference later. This is a Jewish context and son of God is not indication of divinity. It is not a ‘belief’ Evan, it is what Jewish tradition tells us.

How about resurrection, is that a symbol of divinity?

No, see books of Maccabees for vindication and resurrection of martyrs and general expectation of general resurrection in Hebrew Bible. Jesus of synoptics suggests ‘his’ belief in his own vindication and resurrection preceding general resurrection, consistent with Jewish belief.

As for not knowing why ‘Mark’ wrote what he did, I don’t even know why Mark wrote his Novel.

After all, wasn’t the world supposed to be ending? What need was there for a book about what Jesus had done?

It’s a little too obvious to say, but it’s well known that the Qumran writers thought the end of the world was late, yet despite this, they still continued to write…

But did the Qumran writers produce biographies, writing down oral traditions that everybody knew anyway?

Steph, you listed some details that you believe “would not have been made up”. Do you know of any other discipline (let’s say in the faculty of law, or any nonbiblical history, or anthropology) where anyone uses the argument “I can’t see why anybody would have made up this story” to determine what is a fact or not?

I can’t really go beyond what all other commentators here have already covered, but for the sake of my own angle on the question, . . .

Steph, you listed some such “facts”. One was

This explanation is but one of many possibilities for Mark using the time marker. Yet you present it as if nothing else could qualify, thus shutting out any possibility of anyone legitimately questioning your (or Crossley’s or Casey’s?) explanation. If you expand your studies into the field of ancient rhetoric, you will be aware that part of the training of authors was to create such details (apparently otherwise pointless) for the sake of verisimilitude in the creation of fiction. If you expand your studies in the Gospel of Mark to the full range of interpretations out there, you will also realize the very strong possibility that Mark was creating a symbolic detail that was meant to resonate with the similar time-markers at the end of the gospel, thus creating another interpretative bracket for readers.

You refer to Crossley who has

I could point you to a number of critical reviews of Crossley’s work, but you have already made it plain that you see no need to consult reviews critical of Casey, so I assume you have the same reluctance to address alternative arguments to Crossley’s work, too.

You write:

This is an interesting one, and one I have attempted to raise with a number of scholars without success so far. But the question becomes even more interesting — and it turns around completely from the way you have expressed it — if we admit Detering’s proposal that the Little Apocalypse was looking back at the Bar Kochba rebellion. Another consideration is Mark’s contrary theology (he was an adoptionist or separationist, after all) that embarrassed Matthew and Luke. What if those metaphors he took from Isaiah were really meant as metaphors for the whole thing, including the OT interpretation of God’s “coming”, and that it was really a question of Matthew and Luke attempting to literalize Mark?

You wrote:

As rey pointed out, you are assuming something here without any justification. Was there really “the church” that remained on some trajectory from the time of Jesus to the time of the Gospels? This hardly accords with the evidence we have. We know full well that there were other “church” groups or “Christianities” that claimed this or that disciple as their founder, yet these were not in agreement. Matthew’s claim that not all believed might well be seen as a reflection of this diversity and factionalism in his own time.

You wrote:

On what evidence do you base this claim? Kelber and others might have a different view and argue he was attempting to counter “tradition”.

You wrote:

Yes, well. You make much of Doherty’s rhetorical introduction in his book and seem oblivious to what he well knows and argues. The “son of” expression indeed indicates a qualitative likeness to the one who is the “father”. Doherty’s point is, influenced by Mack, I think, that Mark is combining Q and Paul in his gospel. Paul did not see Jesus as a divinity or god type figure?

My explanations here may be wrong, they are certainly debatable. But yours are no better. At least I think I can claim justification by adhering to specific supporting evidence closer at hand for some of mine.

My point stands: To declare any single explanation as the final answer (sounds like “final solution”) is to shut down debate and comparable to the willful blindness of “the divine fallacy”.

I have heard that when Irving Berlin wrote the song White Christmas, he had in mind a woman sitting on a beach in Miami while addressing Christmas cards to her friends in New England. The woman is pretending to be envious of her snow bound friends, but she wouldn’t give up the sunshine for anything. However, Bing Crosby sang the song straight and no one ever thought of it the way Berlin intended it.

Ask any lawyer who has sat on a jury and they will tell you that jurors often draw exactly the opposite conclusion from a piece of evidence that the lawyer who introduced the evidence hopes that they will draw from it. Sometimes this occurs because the jurors misinterpret the evidence. Sometimes the lawyers incorrectly assess the effect the evidence will have. Most of the time, it probably results from the fact that very little evidence is completely unambiguous. (If it was, the case would have been settled before it ever got to trial.)

Every one of Steph’s suggested readings of Mark may be a reasonable (or even the most reasonable) interpretation of his intention and understanding, but I agree with Neil. It strikes me as absurd to propose that any of them are inevitable. We are not capable of reading his mind with that kind of precision.

Your contradiction is incomprehensible. Of course I read critical reviews of both Casey and Crossley – I don’t keep copies at home so I don’t have immediate access to them. Just because a reviewer criticises a book never means it’s wrong or his criticisms are right – in fact they are often unfair and ridiculously biassed. I have never believed that debate should end, and I don’t believe in divine fallacy. I use the criterion of historical plausibility (Theissen, Winter) to argue for some solutions having more weight than others. This can be tied with the criterion of embarrassment in ways that are found in other classical historical studies. There is never a final solution and I never suggested there was. Oh life would be so dull if there were.

STEPH

I use the criterion of historical plausibility (Theissen, Winter) to argue for some solutions having more weight than others. This can be tied with the criterion of embarrassment in ways that are found in other classical historical studies…

CARR

Of course, the ‘criterion of historical plausibility’ can be applied to Harry Potter books.

It is historically plausible that Harry Potter, being a teenager , goes to school.

And the criterion of embarrassment means that Mark must have made up the stories that the church found embarrassing, or else they would have been spun away decades before Mark wrote them down.

Your misinterpretation of the title ‘historical plausibility’ demonstrates you naive lack of understanding of the content of Theissen and Winter. And yes, Mark was slavishly following historical tradition that didn’t reflect too well on the developing perception of Jesus as someone who would not make mistakes. Mark might well invent stories or make additions to stories which cast the disciples in a bad light, but he would hardly make up Jesus making errors in predictions. Even Matthew and Luke had to extend the time expected for end times as it became obvious the original predictions attributed to Jesus were wrong. New Testament scholarship has suffered as a discipline as it has developed independently, and has been dominated by Christians with religious ideals and agendas. That is why it is only recently that scholars like Theissen, Winter and Casey have undertaken the task of developing useful historical criteria. The gospels, like lives of other ancient figures, have a mixture of history and legend, and sorting out the difference requires certain criteria. Also the gospels were written for communities and therefore the criterion of embarrassment can be useful if applied properly. Of course the extreme view of history is that no history can be done on anything at all and that appears to be where the mythers are headed. So of course, the holocaust didn’t happen and nor did many other things…

How do you know Mark was following historical tradition? If you say you can see evidence of it in the text of Mark itself, then your reasoning is circular.

How do you know Mark “would not make up” Jesus pronouncing what later turned out to be a false prophecy? People have always been making up prophecies “in the name of Jesus” that turned out to be wrong.

Jesus was already dead when Mark wrote and Jacob and John hadn’t died with him. So it would be weird for Mark to make up a prediction which was already wrong. Therefore I think it more plausible that Jesus was following historical tradition. And while Mark, who I think for reasons explained by Crossley in Date of Mark, wrote before the fall of the Temple, could easily have made up the saying about the temple being destroyed stone by stone, as he made up most of Chapter 13, I think for other reasons, a general prediction of Temple destruction is likely to come from Jesus. The ‘slavishly following’ was tongue and cheek for the benefit of those who delight in misrepresenting me and assuming I assume things to be ‘fact’ when actually all I do is weigh arguments against each other and decide which I think holds more weight and the gospels, written in the genre of Greco Roman bios, not twentieth century novels or Greco Roman novels are probably going to contain a mixture of history and myth – with John being myth.

Maybe the absurdity should alert you to the possibility that Crossley’s dating of Mark is wrong after all. (The question you raise is certainly not new.)

Much leading scholarship of the Gospel of Mark, however, sees Mark’s prediction of James and John “baptism with Jesus” being symbolic and represented by the 2 thieves, just as Simon was replaced as the cross bearer by Simon of Cyrene. Your literalist/historical interpretation of Mark appears to reject a substantial amount of work on Mark. I trust you don’t reject it on grounds that it is done by scholars who have some partisan theological bias, but consider the merits of the arguments themselves. Your historical reading of at least some parts of Mark’s gospel would seem to me to raise an awful lot of questions that would more readily be resolved by a non-literal/historical reading, as Mark’s gospel itself intimates is the correct way to understand it.

STEPH

So of course, the holocaust didn’t happen and nor did many other things…

STEPH

as philosophers have said, plausibility is a necessary condition but not sufficient for truth, and I have never said any different.

CARR

Of course a true historian says the Holocaust happened because it is plausible that 6 million Jews were killed….

If people really did history in the way that Steph does history, then Holocaust-deniers would have a field day.

Not to mention all the people who believe it perfectly plausible that a second gunman shot JFK.

Thank God that the methods of Biblical historians have not infected real history.

STEPH

Mark might well invent stories or make additions to stories which cast the disciples in a bad light, but he would hardly make up Jesus making errors in predictions

CARR

I see Steph is now comparing mythicists to Holocaust deniers.

When we are more like Harry Potter-deniers.

Of course, any True Believer will tell you that there are no errors in predictions in Mark’s Gospel.

The mere fact that there actually are errors would not be embarrassing.

And, Steph fails to realise that if Jesus really had made ‘errors in prediction’ , of a kind that would embarrass Mark, then these ‘errors in predictions’ would not be in Mark’s Gospel.

People don’t write embarrassing things when they can easily change or adopt them with a stroke of a pen.

So the fact that these ’embarrassing’ things exist prove they were not embarrassing.

STEPH

Even Matthew and Luke had to extend the time expected for end times as it became obvious the original predictions attributed to Jesus were wrong.

CARR

SO clearly the process of embarrasment began with Mark.

Because Mark does not do what later people did proves that the story originated with Mark.

Mark must have been the earliest source of the story.

Or else Mark would have been one of these later sources – the ones who knew the story had to be spun away.

All the criterion of embarrassment proves is that Mark was the very first person to tell the embarrassing story.

Because the second person to tell the embarrassing story would have changed it.

Theissen and Winter’s book, The Quest for the Plausible Jesus, is (mostly) online at Google books. Like Sanders and all mainstream biblical scholars of the historical Jesus that I have encountered, they merely assume without question or verification the existence of an historical Jesus. (Steph’s “independent” scholars are no better, as I show in my review of Crossley’s chapter 2 of Why Christianity). Their criterion of plausibility is a tool for assessing the likelihood of particular sayings or characteristics of this assumed Jesus.

Historical Jesus studies are still at the Albrightian era that characterized ‘biblical Israel’ studies for so long. By circularity it simply assumes the Gospel record is an attempt to record history of some sort, and that it is based on “traditions” back to that presumed historical event. The circularity of the reasoning renders the whole exercise invalid just as the same logical flaw rendered “biblical Israel” research invalid.

Historical Jesus studies need its Philip Davies to begin a methodologically (or simply logically) sound approach to the question of Christian origins.

Glad you could read the whole book so quickly. You’re quite right, Theissen and Winter spend more time sorting out which Jesus traditions are plausible rather than if there are any at all, but no I don’t think it’s all Allbrightian. Allbright was a conservative Christian who believed the whole bible to be true. And while Philip Davies is absolutely clear that he is not a Jesus myther, you have Tom Thompson as your authority. Using his methodology I can prove that even I don’t exist. I’m far too ordinary to be original. As Richard Burridge shows quite well, the gospels are written in the form of Greco Roman bios, in community situations, which is not quite the same as the texts collected in the Hebrew Bible.

I won’t bother responding to Carr who missed the point about Mark – he wouldn’t have been embarrassed – and holocaust deniers – the point was there are many people outside NT studies who deny any history can be done at all. But he continues to misrepresent people and twist what they say.

Steven does sometimes (mischievously and provocatively I think) skip some of the logical steps in the scholarly arguments. He is, as I understand him, making a point about the absurdity of a conclusion that is based on a flawed or groundless premise.

Most who don’t reply to him do so with the excuse of his provocative style or because he has skipped those intermediate “logical steps” expressed by the scholars. They fail to recognize that he is, I think, attempting to bring them face to face with their otherwise hidden assumptions.

Albright did not believe the whole Bible was true. Where did you get that from? I agree fully with Davies that Jesus of the Gospels is a literary construct. I am not a myther either, at least last time I looked up that word in a dictionary.

Thompson is not “my authority”. I don’t have an authority of any kind — I try to be independent and think for myself, but take on board and seriously consider all scholarly contributions of all persuasions. I am surprised anyone can think that TLT’s methods can lead to such absurdities. You must think I have missed something critical about his methods. I do welcome you demonstrating to me how it can lead to such absurdities.

The fact that a large number of scholars currently accept that the gospels are written in the bios genre means nothing for historicity of the narrative itself. Hitler’s and Anne Frank’s diaries were both written in the diary genre. Ancient classical and Christian literature works often enough with literary fictions written in various genres meant to persuade.

Historical Jesus studies are built entirely on the assumption that there is a historical Jesus to study. They ignore the warnings of Hobsbawm, Schweitzer, yes Davies, and Schwartz. None of these are/were Jesus “mythicists”. Some probably never had any interest in the question.

It is their methods that they describe that are “my authority” — and the scholarship about the historical Jesus for most part simply bypasses these sound methods — thus building their whole enterprise on an unsupported assumption.

Historian Eric Hobsbawm on method

Schweitzer on method

Davies on method

he argued in a ground-breaking monograph, In Search of Ancient Israel, that we need to confirm the events of the Bible independently of the Bible itself. This means comparing the Bible record with other historical records. It is naïve to take any book, the Bible included, at face value. We need supporting evidence to know when it was written and if its stories have any truth behind them.

Schwartz on method

(The sources of the citations are in my Crossley review post.)

STEPH

I won’t bother responding to Carr who missed the point about Mark – he wouldn’t have been embarrassed …

CARR

SO the argument from embarrassment has the whole point that the person who made up the story would not have been embarrassed?

With that sort of logic, no wonder nobody has been able to find a historical Jesus. Or rather , there have been about 17 historical Jesus’s that have been found….

STEPH

And while Mark, who I think for reasons explained by Crossley in Date of Mark, wrote before the fall of the Temple, could easily have made up the saying about the temple being destroyed stone by stone, as he made up most of Chapter 13, I think for other reasons, a general prediction of Temple destruction is likely to come from Jesus.

CARR

SO no evidence, just a declaration that there was a Jesus, and a blatant admission that all Steph is doing is reading a Novel and accusing people of being like Holocaust-deniers if they ask for evidence of what she claims is ‘likely’.

Yes, some people do indeed deny that you can do history by reading a Novel and thinking that some scenes in the Novel are plausible.

Just like I deny you can do research on the historical Harry Potter by thinking it very likely that Harry Potter really did go to school, because teenagers in Britain do in fact go to school.

What Steven is saying is no different from what Philip Davies once said about biblical historians of ancient Israel:

How is this any different from what biblical scholars do with the historical Jesus?

The rhetoric is appalling neil. It is not ‘absurd’ at all. It doesn’t encourage one to respond seriously. Most of your questions require longer than blog comment responses – for example demonstrating Thompson’s methodology. A book responding to mythicists directly will be written following the Jesus book by Maurice Casey. I agree with you that James’ model may not be the right one but it is the best attempt so far to try to work one out. However your poking fun at his arguments often reflects you missing the point and your allusions to ‘inferences’ about Jesus and ‘prophets’ and ‘banditry’ are examples where you have missed the point. There is alot of radical scholarship on Mark 10.35-45. You refer to ‘much leading scholarship’ or something similar, without citing your sources. The interpretation of Mark you give is certainly weird and rings vaguely of Jesus seminar stuff but not alot of Markan scholarship at all. Of course the Jesus in the gospels is a literary construct, but like Philip Davies, I think some of the literary material comes from historical sources. Even Philip Davies recognises that the gospels are a different genre from the Hebrew Bible writings.

Steven Carr is determined to misunderstand what I say.

Sorry Stephanie, but you don’t seem to be really reading what I write. I was referring to what you yourself intimated was an absurdity about the implausible scenario of Mark’s “false prediction”. It was not rhetoric but a genuine attempt to invite you to reconsider your assumptions. I regret having apparently offended.

I actually agree with a lot of what you write and say about Davies. Of course the gospel genre is different from anything in the OT. And of course there is very likely some “historical material” in the gospels. I agree. So why the antagonistic warfare-like tone?

I may have joked a little at a small part of Crossley’ argument, but I also have made it clear I liked the guy and I hoped it was seen as good-natured. But if some of his arguments defy logic or evidence then I can only attempt to expose them for what they are. So many scholarly reviews really do try to whitewash their comrades. And a number of people I have encountered take Crossley’s arguments as so thoroughly devastating as to be unanswerable, and one has suggested I have no answer for them. It worries me when people do not seem able to think about what they read for themselves. I am fortunate in having some opportunity to think about some of these issues too, and feel a responsibility to share certain insights in return.

I was certainly attempting to address his points seriously, with solid evidence and logic. If I have missed the point anywhere I would sincerely appreciate more constructive comments from you to alert me to where I have specifically done so.

If TLT’s methodology is bizarre it can be summed up without all the details in a few lines — to say you need a book to explain why it is bizarre suggests to me that you have no real case. I suggest scholars regularly sum up the basic premises of others whenever they address histories of an argument. This is routine.

As for my interpretation of Mark, I merely said much of it was not meant to be read literally. I did not think that was controverial at all: Kelber, Fowler, Myers, Wrede, MacDonald, Kee, Kermode, Weedon and others that don’t come to mind just quickly (though I have discussed oodles in my Mark archive). The idea that Mark is a parable as a whole, or that he writes much by way of theological symbolism, is certainly well-known and surely uncontroversial — you may not agree with these views, but they are well accepted scholarly views.

I certainly agree that much mainstream biblical scholarship is riddled with sham, including much of the Jesus Seminar stuff. I have recently addressed the contradictions and circular reasoning in Robert Funk’s methodology.

But if the Sheffield Uni biblical studies unit wants to be truly independent, they need to examine all of the assumptions and methodologies they have inherited from the non-independent scholars, and get in line with the basics of external controls for establishing the historicity of any document’s narrative. Truly make biblical history like any other history. Without exceptional methods and free-for-all assumptions that no other history departments would tolerate.

you haven’t offended me at all – I understood perfectly what you were implying and ‘absurd’ is hardly new in your vocabulary of rhetoric. What I suggested was not at all absurd at all. It is hard to take you seriously.

Kermode is not a NT scholar, Dennis MacDonald can hardly be seen as a leading Markan scholar – it’s a very american list though it doesn’t include Collins and Marcus. Of course NT scholarship is riddled with beaurocracy and sub cultures and religious agendas. We are doing our best to transform this without debunking the whole process of doing history at all.

Of for pete’s sake. Let me add Carrol, then, an Australian (I’m an aussie :-), who wrote about the Existential Jesus in Mark’s gospel. I know, he’s not a NT scholar either, but give a bit of leeway — Crossley does want to open up the study to wider fields, after all. I am sure if you want you can find many UK scholars who also agree that Mark is in many areas written allegorically. I don’t believe you can divide up those who think this way either side of the Atlantic. You seem determined to refuse to address any of the arguments or requests for evidence I and others have put here. Most of your responses are to find fault with some detail that sidesteps the actual arguments and requests for evidence.

Why not address the simple point that Crossley and Casey do not even meet the basic requirements of determining what is evidence in nonbiblical histories (e.g. Hobsbawm, and Lemche’s and Davies’ discussions, too, and Schweitzers, and Schwartz)? Or simply sum up the basic error in Thompson’s methodology.

I sometimes get the impression you are repeating only what Casey and others in your uni teach and how they guide your interpretations of others, and you’re not so independent at all. Prove me wrong.

ETA: As for Kermode being a literary critic — yes, and he has much to offer. Even Davies says literary criticism has much to offer in the case of OT studies. Maybe, just maybe, if we dare step out to be a little independent . . . .

I hadn’t heard of Carrol who isn’t a NT scholar and you do not seem to realise you have listed a group of mostly american literati. I know of no NT scholar in the UK who holds this view of Mark as allegorical. Therefore mainstream scholarship does not hold this view at all. I came 12 thousand miles after graduating at Victoria to study with sane scholars when I could have chosen to go to america to study with american literati. In Crossley’s general discussion of historians and others in ‘Defining History’ (Crossley and Karner eds, Writing History, Constructing Religion, Ashgate 2005) Crossley quotes the well known historian GR Elton objecting to ‘people who would subject historical studies to the dictates of literary critics’ which seems to fit this situation quite well. The basic problem with Thompson’s methodology is that he assumes if something has been said before it can’t be repeated and his assumption that he can find ancient parallels reflects his defective sense of similarity and dissimilarity, as for example when he announces that the passion narrative ‘reiterates’ the myth of Dionysus (p. 205). Now that is a very simplistic description and requires further qualification – the trouble with demanding an answer to such a big book in a short comment on a blog. The notion that I only repeat what Casey and others teach is ridiculous and will be obvious in my thesis which is my own original work and often expresses different opinions.

I have removed my response and decided not to continue my involvement in this discussion.

steph:

And yes, Mark was slavishly following historical tradition that didn’t reflect too well on the developing perception of Jesus as someone who would not make mistakes. Mark might well invent stories or make additions to stories which cast the disciples in a bad light, but he would hardly make up Jesus making errors in predictions. Even Matthew and Luke had to extend the time expected for end times as it became obvious the original predictions attributed to Jesus were wrong.

I think it’s underappreciated that use of the idiom of apocalyptic needn’t force us to believe that the author was making predictions or necessarily had certain historical expectations. Mark to me seems more “slavish” in its adherence to Daniel as a model than to any identifiable history. And, as in Daniel, apocalyptic is used as a means of making cryptic commentary on the current situation of the author and the implied community or audience.

I agree with Neil when he says that what we see in Matthew and Luke when the authors of those texts “correct” Mark’s “failed predictions” is a function of their intentions toward literalizing an extended parable that was not meant to be construed as a prediction at all.

I explained that comment in a later comment. That particular prediction may well have been made up by Mark if he was writing before the fall of the Temple but James and John certainly hadn’t died with Jesus when Mark wrote his gospel. It do think however the prior predictions in Mark 8.31 have historical basis and after all, predictions of such things is hardly unlikely for a Jewish historical Jesus. Matthew and Luke were quick to correct Mark when they weren’t ‘fatigued’.

I respond to your now deleted comment because you made many inferences which do not follow from what I have said. I have read what you have written and I do not confuse mainstream scholars with consensus. Individual mainstream scholars do not hold this view. Compare Morna Hooker whose scholarship is perfectly sane and not consensus, also Collins and Marcus who don’t agree with everyone but are perfectly sane, and I don’t always agree with any of them at all.

As I have already noted I do disagree with Casey on quite fundamental issues. I don’t call UK NT scholarship ‘literati’ because they are not heavily beaurocratised like the majority of American scholarship.

Elton was discussing the nature of approaches to evidence and objecting to literary critics taking over. As for ‘dictates of literary critics’, I was quoting Elton, as others have, because he was such a good secular historian.

As for my description of Thompson’s sense of similarity and dissimilarity as ‘defective’ being a Casey type ‘ad hominen innuendo’, this is totally untrue. It is an important point of method that he cannot comprehend the difference between similarity and dissimilarity and my example of the passion narrative compared with the story of Dionysus is a perfect example of dissimilarity.

Hobsbawm was a left wing Marxist who focused on left wing Marxist things which are important, but not necessarily applicable everywhere – and you should have noticed me quoting Elton, a ‘nonbiblical’ historian.

And finally, I don’t agree with what you say about all NT scholars not using methods of secular historians. However I will need to gather the evidence from the library, citing secular non biblical historians such as Evans ‘In Defence of History’ and McCullagh ‘The Truth of History’. I will do this.

You can save yourself the trouble of gathering evidence from Evans and McCullagh. They discuss philosophy of history. Simply address the question of Hobsbawm’s method (his political and philosophical leanings are irrelevant to the question — but do note that even Crossley uses him for his Why Christianity Happened!) of the simple requirement for the need for external controls. External controls — as cited by Schweitzer and Hobsbawm and Schwartz and Thompson et al — it’s as simple as that. Just address why biblical historians (alone) do not need external controls to establish the historicity of a narrative. I withdrew from the discussion because this was my point from the beginning and the one point — as again in your latest post — that is persistently sidestepped. Not just by you, but by a number of other biblical scholars (American and British alike) claiming to be “historians”, too.

particularly reading classical historians on ancient lives and histories – such as by Pelling and Troester.

I am finding the research very interesting. Of course I’m including other historians as well as ancient historians and primary source material. One of the main reasons there is not much existing external evidence of Jesus is because Christianity was not prominent in the early Greco Roman world when Josephus and Tacitus were written. Those Jews who acknowledged him became Christian (see Paul, Matthew etc) so we can’t count these as external controls. Histories of other figures are of interest to shed more light on availability of external controls. My whole argument has never claimed ‘fact’ – it has always been about historical plausibility as I have tried to explain – it is just more likely he existed than alot of the material has been made up, and this requires a very thorough demonstration of the first century context. It is precisely the lack of external evidence available that makes the criterion of embarrassment useful against people who claim Jesus is a myth. The criterion of embarrassment is only necessary when most of the early primary sources are written by members of a single movement which is not generally the case.

STEPH

It is precisely the lack of external evidence available that makes the criterion of embarrassment useful against people who claim Jesus is a myth. The criterion of embarrassment is only necessary when most of the early primary sources are written by members of a single movement which is not generally the case.

CARR

Of course, the criterion of embarrassment means Mark made up a lot of stuff, as later Christians found it embarrassing.

As Mark was writing decades after the alleged facts, he was already a ‘later Christian’. If these stories needed to have spin put on them, Christians would already have had decades to work out what to spin on them.

So either Mark did not find his own words embarrassing, or Christians were just so dumb, that it took them decades to realise that they should not blurt out embarrassing truths.

The first alternative – that Mark was not embarrassed by his own words – is far more realistic.

As for external controls, clearly Christianity did not make much impression on Christians. No Christian in the first century ever named himself as having heard of Judas, Thomas,Mary Magdalene, Nicodemus,Lazarus, Joanna, Salome etc.

In fact, Steph is right. Jesus made so little impact that Jude talked about Adam, Moses, Sodom and Gomorrah, Enoch. Jesus was just not on the radar for Christians like the authors of James and Jude.

Similarly, Jesus made so little impact on Paul that Paul could write 16 chapters of theology without checking what his boss had said on the subject.

You’re consistent SC at misinterpreting, contradicting and missing the point.

So still no arguments from Steph. She must wish she could counter my arguments with something other than abuse.

STEPH

One of the main reasons there is not much existing external evidence of Jesus is because Christianity was not prominent in the early Greco Roman world when Josephus and Tacitus were written.

CARR

So did Tacitus get his information from Christians, or perhaps from his friend Pliny the Younger?

I did not counter any arguments. I ignored assertions based on an assumption of extraordinarily late gospel dates. I ignored misrepresentation and contradiction.

Perhaps Steph finds her arguments and evidence too embarrassing to mention?

That is plausible, so it must be true. That is the logic she uses.

missed the point as usual.

as philosophers have said, plausibility is a necessary condition but not sufficient for truth, and I have never said any different.

STEPH

NEIL

Steph, can I explain why this reasoning (it is a very common argument) does not persuade me?

It begins by assuming that the gospel narrative has some historicity when that is what we are trying to find out. The logic is circular. It is the same as saying that there is not much control evidence for alien visitations because aliens try to avoid making a grand public appearance. Now that indeed might be true. But just saying it does not prove it or make any sort of case for it. One might just as plausibly assert that there is no control evidence for alien visitations because they don’t happen and other factors can explain the few claims that they do.

STEPH

NEIL

I wonder if you might be confusing plausibility with probability here. Historians – especially historians of ancient times — work with degrees of probability of people and events. (Plausibility goes without saying.)

STEPH

NEIL

Why is it more likely? We have many very lengthy writings about made up people and other types of personalities from Greco-Roman times. Why is Jesus an exception? What is it, exactly, about the first century context that makes it more likely? I can find a lot of good reasons to explain why the Jesus story would have been made up. But more than rationalizations on either side, what is needed is evidence. Without it, we have no idea, only guesswork, assumption. (If you are thinking of Crossley’s and Casey’s arguments based on internal evidence for an early date for Mark, you need to address the fact that their arguments are also circular — they are based entirely on the assumption that there was an historical Jesus around 30 ce in Palestine. Without that assumption their whole argument collapses. There are other very simple ways of explaining those same internal details in Mark without assuming an early provenance.

STEPH

NEIL

The criterion of embarrassment is also based on circular reasoning. It begins be assuming that a certain idea would have been embarrassing to an original author, and then using the “embarrassing text” to then “prove it”. Yet there are good reasons to think that those details were simply not embarrassing at all to the original authors. The idea of a hero suffering unjustly, being rejected by his loved ones, etc, etc. — all of this is the common tropes of classic folktales and fictions everywhere. They are not embarrassing details at all — they are what makes the hero heroic and deserving of our sympathy.

far too late to consider now here but scrolling down to the bottom, interesting that ‘trope’ leaps out. Reminder of Thompson who reduces everything to ‘tropes’ like the apparent ‘trope’ of the itinerant prophet – the trope of the Jesus seminar Jesus, the Jesus seminar which is his focus of fire, the Jesus seminar which he thinks mainstream scholarship perceives as ‘conservative’ which might be true of his own social sub group but certainly not the view of mainstream scholarship. But as I said it’s late now and I may read your comment if I have more time.

Sorry not prepared to give too much time to this…

Historically plausible as a criterion for Jesus means that tradition must be historically plausible in a first century Palestinian Jewish environment and not in a Hellenistic cult.

Good reasons have not been shown for the Jesus story being made up or for thinking those reasons for embarrassment are not embarrassing at all.

It isn’t a single flowing ‘gospel narrative’ and detailed analysis of Greek text and literary criticism has demonstrated that it is a compilation of traditions which Mark (the earliest gospel for literary reasons) for example has woven together. Separating these traditions reveals that some have a very Jewish context and some have a very other context. Some of those with the Jewish context don’t sit too well with the audience of the other context and wouldn’t exactly have been made up by them either…. so why make them up? Reasons have not been given.

Aliens are not historically plausible. A first century Jewish prophet in a first century Palestinian Jewish environmnent is.

Your common trope lumps together lots of things which are vaguely similar and suitable subjects for fiction as well as history but they don’t take account of various details of the story eg being crucified as a common criminal.

Steph, you often complain Steven misses the point. But that’s exactly what you are missing in both his and my posts just about every time.

but I think you are missing the point about detail. You paint everything with broad brush strokes. Of course you can talk about circularity when you simplify things to the degree you do. You’re both irredeemable – for slightly different reasons. Naturally this conversation is pointless.

All attempted mythicist explanations for story are completely unconvincing. And what ‘external controls’ do they have for their ‘reconstructions’ of christian origins?

But you have read Doherty enough to be able to address what he says and believes in your thesis, so I know you know the answer to this one. But if you are more serious than the American scholar James McGrath in asking such a question, I am surprised at your sceptical tone. I would have assumed an independent thinker would investigate arguments before dismissing them with rhetorical questions. 😉

Steph ‘A first century Jewish prophet in a first century Palestinian Jewish environmnent is.

‘

And a sailor who eats spinach is also plausible.

STEPH

Good reasons have not been shown for the Jesus story being made up or for thinking those reasons for embarrassment are not embarrassing at all.

CARR

In other words, Christians were too dumb to realise that they should put spin on these ’embarrassing’ stories, so after 30 years Mark just blurted out these embarrassing truths.

In reality, if something was embarrassing , it would have been written out of the life of Jesus before he was cold in the grave.

But ‘Real Historians’ think these stories survived for decades and were retold by oral tradition, although Christians squirmed with embarrassment every time they told them to their friends.

Real historians have never met religious people, who will happily rewrite history of a few days ago, let alone history of a few decades ago.

STEPH ‘A first century Jewish prophet in a first century Palestinian Jewish environmnent is.

CARR

The earliest Christian writings never mention a prophet.

So Steph slams mythicists because only the ‘prophet’ hypothesis can explain why the earliest Christians never talk about a prophet.

She demands that mythicists produce an explanation of Christians never mentioning a prophet that is half-way as good as her explanation that they were talking about a prophet.

It isn’t a single flowing ‘gospel narrative’ and detailed analysis of Greek text and literary criticism has demonstrated that it is a compilation of traditions which Mark (the earliest gospel for literary reasons) for example has woven together. Separating these traditions reveals that some have a very Jewish context and some have a very other context. Some of those with the Jewish context don’t sit too well with the audience of the other context and wouldn’t exactly have been made up by them either…. so why make them up? Reasons have not been given.

The search for these “traditions” the author of Mark “wove together” has turned up as many descriptions as there are for the Emperor’s outfit. Most mainstream scholars are convinced they must have existed; there is very little consensus as to exactly which pericopes they consisted of. It may be that the author of Mark was an unevenly assimilated/acculturated Greco-Roman diaspora (Syrian) Jew, whose notions of what “sat well” with what else defy the usual attempts to characterize 1st c. Jewish beliefs in the Eastern Mediterranean. There are credible critical readings in which Mark can be seen very much as an integrated narrative, largely the work of a single author. Whether the narrative is “flowing” by some arbitrary modern standard is hardly a compelling criterion for abandoning the default hypothesis about a narrative, that it is the imaginative creation of a single person who conceived and executed it. It actually posits far more literary skill on the part of the author to imagine that he was able to so comprehensively subsume these diverse “traditions” into a framework largely determined by his “master parable,” that of the Sower, than that he simply wrote the thing, under the influence of a larger (and ancient) literary tradition, and his narrative imagination, of which there has never been a shortage.

I would ask for the key points you believe are the most telling from this detailed analysis of the Greek, but heretofore it’s been precisely at that level of engagement with the argument that you seem suddenly to lose interest in this “meaningless” conversation, so why bother.