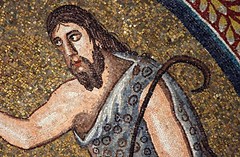

Of John the Baptist Professor E.P. Sanders (Jesus and Judaism) writes:

That John himself was an eschatological prophet of repentance is clearly implied in Josephus’s account. Further, the depiction of John and his message in the Gospels agrees with Josephus’s view: the preaching in the desert; the dress, which recalled Elijah; the message of repentance in preparation for the coming judgment. These features correctly pass unquestioned in New Testament scholarship. (p. 92)

Associate Professor James McGrath called on anyone sceptical of the historical Jesus to engage a scholar like Sanders point by point (and cited Jesus and Judaism specifically) and see if they can arrive at different conclusions for historicity.

I have already covered the point in Sanders’ own chapter 1, the Temple Action of Jesus. Here I look at just a small detail, but one about which Sanders makes some remarkably strong assertions about historicity and even external controlling evidence for historicity.

Compare what Sanders writes above with the actual account of Josephus that Sanders says supports everything he says. From Josephus.org:

Antiquities 18.5.2 116-119

Now some of the Jews thought that the destruction of Herod’s army came from God, and was a very just punishment for what he did against John called the baptist. For Herod had him killed, although he was a good man and had urged the Jews to exert themselves to virtue, both as to justice toward one another and reverence towards God, and having done so join together in washing. For immersion in water, it was clear to him, could not be used for the forgiveness of sins, but as a sanctification of the body, and only if the soul was already thoroughly purified by right actions. And when others massed about him, for they were very greatly moved by his words, Herod, who feared that such strong influence over the people might carry to a revolt — for they seemed ready to do any thing he should advise — believed it much better to move now than later have it raise a rebellion and engage him in actions he would regret.

And so John, out of Herod’s suspiciousness, was sent in chains to Machaerus, the fort previously mentioned, and there put to death; but it was the opinion of the Jews that out of retribution for John God willed the destruction of the army so as to afflict Herod.

How much of what Sanders’ says is “correctly unquestioned” really “agrees with Josephus”, as he clearly infers.

The evidence for John being an eschatological prophet?

Read the Antiquities passage again and you will see it is simply not there. There is not a breath of a hint that John was an eschatological prophet. But Sanders knows this, so why does he say “that John himself was an eschatological prophet of repentance is clearly implied in Josephus’s account”?

That John was an eschatological prophet is less clear in Josephus, who here as elsewhere probably downplays eschatalogical features. (p.371)

Sanders seems to miss the axial point here. The reason Josephus downplays eschatological features, if he does indeed do that here, is because he makes it clear elsewhere he is personally viscerally opposed to such rebellious notions. If he suspected as much of John the Baptist how could he possibly have spoken about him favourably, without a hint of censure at any point at all?

But what evidence is there here in Josephus that such expectations are played down at all? There is no hint of any such expectations in John’s teaching according to Josephus. In the Gospels scholars often claim that Matthew and Luke and John downplay the scene of the baptism of Jesus in Mark’s gospel by (a) having Jesus either apologize for it (Matthew) or (b) not linking Jesus’ baptism with John (Luke) or (c) not mentioning the baptism of Jesus (John). But in Josephus we have no evidence to suggest to us that Josephus had any notion of John being an eschatological prophet.

So why does Sanders claim that Josephus implies that he did preach an eschatological message? Answer:

[Josephus] writes that Herod had him executed because he feared that trouble would result. Baptism and piety do not account for that reaction, and a message of national redemption is thus made probable. (p.371)

Look at Sanders’ reasoning here. He rejects the narrative of Josephus as we have it because it is implausible. It reads, just like the gospels, as a fairy tale. The gospel narrative of John’s death is just as plausible as the reason we read in Josephus, and both reasons are quite similar to each other. Herod fears the very popular John denouncing him for his sins, so has him arrested.

Thus in Herod’s motive for arresting John, Josephus and the gospels closely agree. But Sanders does not find this reason plausible in either tale.

Rather than ask the question, then, about the veracity of Josephus’s portrait of John, Sanders seeks to save his historicity by conjuring up an element from the gospels: that John was preaching the end of the present age and a new age of judgment to come.

Sanders then claims, with dizzying circularity, that the Josephus account supports the Gospel narrative!

On the other hand, one can find a very near at hand ready-made piece of evidence for the source of the Gospel depiction of John as an eschatological prophet. It is in Malachi and Isaiah — the very prophets the earliest gospel, Mark, quoted to introduce his scene of John. Both of these introduce a messenger, like Elijah, calling out in the wilderness and warning of the judgment to come:

Isaiah 40:3,4,10

The voice of one crying in the wilderness:

“Prepare the way of the LORD; . . . .

Every valley shall be exalted,

And every mountain and hill shall be made low; . . . .

Behold, the Lord GOD shall come with a strong hand . . . .

and Malachi 3:1,2

Behold, I send my messenger,

And he will prepare the way before me.

And the Lord, whom you seek,

Will suddenly come to his temple. . . .

But who can endure the day of his coming?

One does not need to fabricate motives to convert a fairy tale story into a historical one. The author of the Gospel of Mark as good as tells readers exactly what was his source for John being an eschatological prophet. He could not wink and nudge any harder without doing himself muscular damage.

The evidence for John preaching a baptism of repentance for the remission of sins?

I am prepared to give Sanders just a small wee bit of leeway on this one. Josephus does decidedly portray John as preaching that people must live virtuous lives. It was a precondition to baptism. It’s not quite “repentance”, but I won’t quibble.

But was John’s baptism a “baptism of repentance for the remission of sins” according to Josephus? Hardly. If anything, Josephus appears to be going to some trouble to explain that it was NOT a baptism of repentance and that it had nothing to do with putting away sins, but was instead a baptism for those already living righteously to undergo some sort of ceremonial purification of the body. Josephus explains that John’s baptism was for the purification of the body; the gospels say it is for the remission of sins.

In the gospel of Mark the people come to John for baptism confessing their sins. In Josephus they came to John for baptism having finally turned around and having been living righteous and pious lives. There is a conflict here. We do the evidence less than full justice if we casually assume that the Gospel narrative and character of John is supported by Josephus at this point.

Is there evidence of another (nonhistorical) source that was immediately available to the author of the gospel that is staring us in the face?

There certainly is, and it is the same chapters 3 and 4 of Malachi that the evangelist applied to John in his narrative: Mark 1:2 and Mark 9:12-13. Here the whole theme of the Elijah message is repentance.

The evidence for John preaching in the desert?

Sanders writes that in the depiction of John and his message in the Gospels agrees with Josephus’s view, that John preached in the desert.

But Josephus nowhere suggests that John preached in the desert. For all we know from the Josephan passage John could have been preaching in any place, urban or rural, beside a pool of water.

But Mark does indicate his own source for the desert setting, and again it has nothing to do with oral tradition:

The voice of one crying in the wilderness . . . . (Isaiah 40:3 and Mark 1:3)

The evidence for John dressing up like Elijah?

Sanders writes that in the depiction of John and his message in the Gospels agrees with Josephus’s view, that John dressed like Elijah. Or maybe Sanders did not mean to say this, and would have restructured his sentence had he noticed the gaffe.

Josephus at no point hints anything about John’s clothing at all. But again, Mark does inform us that his source for the idea of giving John the Elijah appearance is directly from his reading of Malachi.

Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet (Mal. 4:3)

and

And [Jesus] answered and told them “Elijah does come first, and restores all things . . . But I say to you that Elijah has indeed come . . .” (Mark 9:12-13)

The power of the gospel narrative to materialize everywhere

Maybe Sanders was writing this passage at the end of a late night, or maybe his passage is yet one more testimony to the way the gospel narrative can tyrannize our assumptions so powerfully that we tend to see it repeated in anything that even reminds us of it.

That John himself was an eschatological prophet of repentance is clearly implied in Josephus’s account. Further, the depiction of John and his message in the Gospels agrees with Josephus’s view: the preaching in the desert; the dress, which recalled Elijah; the message of repentance in preparation for the coming judgment. These features correctly pass unquestioned in New Testament scholarship.

Not a single one of these details appears in both the Gospel narrative and the Josephan account — except for the name of John the Baptist himself, and that he preached something. It appears that Sanders has read the very familiar Gospel narrative into the passage in Josephus, and then written that Josephus is external support of the Gospel narrative.

(We also have other issues with this John the Baptist narrative, such as its setting about ten years after the time of the Gospel setting for Jesus, and there are also legitimate questions about some unJosephan details and awkward position in the text which raise the possibility of it being an insertion by a follower of a John the Baptist sect. But those are other discussions for another time.)

The need for external controls to support the historicity of the Gospel narrative

Scholars know that the Gospel narratives need external controls in order to establish their historical validity. Josephus is about all they have and they need him to witness to the Gospel narrative.

But in the instance of John the Baptist, Josephus does not witness to the historicity of the Gospel narrative. The Gospel portrayal of John the Baptist is drawn entirely from passages in the Jewish scriptures, as shown above. It does not come from oral tradition or any kind of historical memory.

So when E. P. Sanders writes of the biblical depiction of John the Baptist::

These features correctly pass unquestioned in New Testament scholarship

he illustrates the shallowness of much that passes for that New Testament scholarship.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I won’t hold my breath waiting for McGrath’s reply.

SANDERS

Further, the depiction of John and his message in the Gospels agrees with Josephus’s view: the preaching in the desert; the dress, which recalled Elijah;

CARR

Wow!

They both wore a leather belt. I wear a leather belt. Perhaps I am Elijah returned to the Earth?

Either this is a perfect example of what historicists call ‘parallelomania’, or it really is true that such details as ‘leather belts’ are enough to establish parallels between two people.

What exactly are the criteria which distinguish ‘parallelomania’ from ‘mainstream Biblical scholarship’?

Is it ‘parallelomania’ when the parallels support mythcism, and mainstream Biblical scholarship when the parallels support the idea that there was Jesus who pointed out these parallels?

‘Associate Professor James McGrath called on anyone sceptical of the historical Jesus to engage a scholar like Sanders point by point (and cited Jesus and Judaism specifically) and see if they can arrive at different conclusions for historicity.’

I think you’ll find that McGrath castigates mythicists for engaging a scholar like Sanders point by point. It is nothing more than trying to pick holes in the historicist case, and demonstrates their creationist like tactics.

How do creationists respond when evolutionary scientists nit-pick their theories with facts and logical arguments?

I’m so often tempted to do a creationist-McGrath set of parallels, and use an independent portrayal of creationism to avoid the charge of tendentiousness, but then that would not be playing by the rules, would it.

‘I am prepared to give Sanders just a small wee bit of leeway on this one.’

You have to refute Sanders point by point.

Sanders, of course, is not wrong about everything.

So it is impossible to refute every point Sanders makes.

So McGrath will simply claim that Sanders has not been refuted ‘point by point’, even if the points where Sanders is correct do not amount to very much of a case for historicity.

Notice also that you cannot refute Sanders points for the historicity of Jesus, because he doesn’t make any.

So Sanders is not refuted…..

when I was informed that one, whose name was Banus, lived in the desert, and used no other clothing than grew upon trees, and had no other food than what grew of its own accord, and bathed himself in cold water frequently, both by night and by day, in order to preserve his chastity

Maybe E. P. Sanders had the gospel-John the Baptist like “Banus” who is mentioned in Josephus’ “Life” in mind?

As I remarked on another thread, I don’t really expect a dialogue with James over my Sanders’ discussions. I’m sure he won’t even know about them, let alone read them. But he did give me a neat rhetorical foil with which to introduce my own thoughts on what passes for so much of mainstream biblical scholarship.

The scholarship on JoB is, in general. weak. The best neutral account on JoB that I found is, believe it or not, in the Jesus Seminar’s report, one of the very few to consider Ensiln’s old position on JoB being historical but not connected to Christianity (and then only in a footnote, but that’s better than nothing, I guess) which I think is the most probable scenario of several possibilities. I agree that JoB is not eschatological in Josephus; J. has no problem bashing other folks with eschatological beliefs in the 1st century. Why give this one a pass?

Mark does indeed give us his inspiration here. I wonder if the Isaiah bit was an invention of those that thought John the Baptist should have Isaiah’s traits or if John imitated Isaiah?

As to his setting in the wilderness, if they had wanted him somewhere else do you not think it possible to find another verse to use a a prophecy? Was the selection from Malachi the only one G.Mark could use here?

And there is the possibility that Mark’s audience might themselves be familiar with John the Baptist legends? They do seem interested in incorporating him into there myths, whether he belongs or not. That would seem to work against including anything that was outside the common beliefs about the man. If his clothing wasn’t much discussed you could sneak in him wearing the hair shirt, but if his signature outfit was silk pajamas, then the new item is a bit harder to work in.

On the Baptist baptism, It is possible that Josephus is mistaken, I mean what are his sources? John was a slightly notable religious fanatic a generation before his own time, what would be know for certain? Groups that revered may have more incentive to preserve his teaching, or conversely, to corrupt it to give there own practices greater authenticity. Certainly the idea of Baptism as death and rebirth are not a part of John’s belief and so it is possibly that it was for forgiving sins may not be his either.

I don’t think much is certain one way or the other beyond his work with water, preaching something, and his sad end at the hands of authority.

> …or maybe his passage is yet one more testimony to the way the gospel narrative can tyrannize our assumptions so powerfully that we tend to see it repeated in anything that even reminds us of it.

Not only does the “gospel narrative” shout over top of our immediate perceptions, but it also seems we who were raised as Christians carry around an internal Diatessaron. I thought of this recently when I was reading various on-line summaries of the post-crucifixion acts of Joseph of Arimathea. People seem instinctively to smash the conflicting stories into one semi-coherent narrative, which none of the gospel writers would likely agree with.

Mark: “Who’s this Nicodemus character?”

Matthew: “Whoa, whoa, whoa! Joseph was just a rich man, not a disciple.”

John: “I never said the tomb was Joseph’s. It just happened to be nearby and it was getting dark.”

Luke: “One hundred pounds of myrrh and aloe? Seriously? What, did they rent a truck?”

The voice in Mark that cries out in the wilderness is misplaced. The NRSV has it right:

“A voice cries out:

‘In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord,

make straight in the desert a highway for our God.

Every valley shall be lifted up,

and every mountain and hill be made low;

the uneven ground shall become level,

and the rough places a plain. ”

The voice is in the city of Babylon, celebrating the end of captivity and describing the straight and level route through the desert to Jerusalem.

In defense of the gospel authors, it’s a lot harder to read clearly when you are looking for justification or foreshadowing, rather than trying to understand the text.