edited and added TLT quote Jan 26, 2010 @ 20:05

I think of myself as neither a “Jesus mythicist” nor a “Jesus historicist”, but as someone interested in exploring the origins of Christianity. Whether the evidence establishes a historical Jesus at its core, or an entity less tangible, then so be it. Nonetheless, I cannot deny the importance and implications of the question.

Two things that bug me about much of the historicist position are:

- many of its interpretations of the evidence are grounded in circular reasoning

- many of its arguments are rhetorical and/or built on the fallacy of incredulity (aka “the divine fallacy“)

There are things that bug me about some mythicist arguments, too. But here I want to share the first of a series of responses I am making against the historicist position as summed up by a contributor on a Richard Dawkins website discussion forum.

In summary:

(i) [Jesus] existed

The idea that the stories about him are based on a historical figure is the most parsimonious explanation of how they arose, since the alternatives require repeated suppositions to explain away key elements in the evidence (eg all those “maybes” required to make references to his brother etc disappear).

This would be true IF the earliest evidence is for a more human Jesus, with the later evidence demonstrating an emerging divinization of this person until he eventually reaches co-creator and sustainer of the universe god status.

But the evidence we do have is actually the reverse of the above. The earliest evidence — such as an early hymn quoted by Paul (Phil. 2) — describes Jesus as equal with God, who had a brief temporary transformation to look like a human in order to be killed to effect a theological saving destiny for humankind, and was restored to the highest God-status and given the new name of Jesus, and worshiped by all as a reward.

. . . . Christ Jesus:

Who, being in very nature God,

did not consider equality with God something to be grasped,

but made himself nothing,

taking the very nature of a servant,

being made in human likeness.

And being found in appearance as a man,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to death—

even death on a cross!

Therefore God exalted him to the highest place

and gave him the name that is above every name,

that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father.

Paul’s Jesus as referenced in the rest of his letters hews to the same identity. Jesus for Paul is the Spirit and Wisdom of God, a God-head figure of worship, whose exalted heavenly status is the honour bestowed on him for his descent into at least some form of flesh for the purpose of crucifixion.

It is the later evidence (among the gospels) that seeks to humanize Jesus. In Mark, he is said to become possessed by the Son of God spirit, lose his temper and need a couple of shots at healing a blind man. In Luke and Acts, his death is described as that of a merely righteous human martyr. A later copyist even added a scene with him sweating blood.

The most parsimonious way to describe this trajectory of the actual evidence is to see Jesus as beginning his history as a heavenly figure whose temporary appearance in the form of a man became the subject of later elaborations.

He is mentioned by Josephus twice and by Tacitus once and the arguments required to make these clear references in two independent sources disappear require, once again, a small hill of suppositions and contrived arguments.

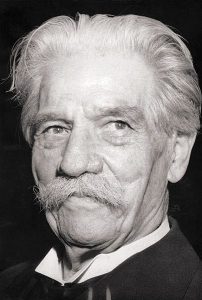

On the contrary, the contrived arguments are those that have emerged since the Second World War when many things changed. Prior to that time the scholarly consensus — a consensus that included names like Albert Schweitzer and Walter Bauer — was that these texts are worthless as testimony for the historicity of Jesus. So to accuse anyone who dismisses the value of the Josephus evidence of resorting to “contrived arguments” is to insult some of the greatest names in the history of biblical scholarship.

On the contrary, the contrived arguments are those that have emerged since the Second World War when many things changed. Prior to that time the scholarly consensus — a consensus that included names like Albert Schweitzer and Walter Bauer — was that these texts are worthless as testimony for the historicity of Jesus. So to accuse anyone who dismisses the value of the Josephus evidence of resorting to “contrived arguments” is to insult some of the greatest names in the history of biblical scholarship.

Sometimes intellectual changes reflect broader cultural developments, and this seems to be one case in point. It appears to coincide with the shift in scholarly consensus to exonerate or excuse Judas, and other scholarly research designed to emphasize the Jewishness of Jesus. Western guilt over past anti-semitism has been proposed as one explanation for some of these scholarly shifts. I suspect something similar at work in finding ways to bring the Jewish historian Josephus and Jesus together.

The stories about him contain elements which are clearly awkward for the gospel writers (his origin in Nazareth, his baptism, his execution) and which they try, largely unsuccessfully, to explain away or which they downplay or remove. These elements are awkward because they don’t fit the expectations of who and what the Messiah was, yet they remain in the story.

Apart from the subjectivity of deciding if a narrative detail is “clearly awkward”, this argument rests on a false premise.

The fact is that there is no evidence for some general expectation among Jews for any particular type of Messiah at all in the period discussed.

In a review of the most detailed discussions of the idea of the Messiah among Jews of the Second Temple period, The One Who Is to Come by Joseph A. Fitzmyer, Jeffrey L. Staley writes:

There is no serious attempt to place messianism within the broader matrix of social history. There is no interaction with, say, Richard Horsley or John Dominic Crossan’s work on social banditry and peasant movements (Bandits, Prophets, and Messiahs: Popular Movements in the Time of Jesus; The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant). One might then ask of Fitzmyer what communities he thinks are reflected in his textual study. If, as many have suggested, only 5 percent of the ancient Mediterranean population could read and write, then what segment of the population is reflected in Fitzmyer’s analysis? Is his “history of an idea” representative of Jewish belief at large, or does it represent only a small segment of the population? Does Fitzmyer’s study of the “history of an idea” reflect only the elites’ mental peregrinations, which are largely unrelated to the general masses? And what difference, if any, would his answer to this question make to this “history of an idea”?

Thomas L. Thompson, The Messiah Myth, has discussed in detail the literary nature of this messianic ideal (a literary construct that extends beyond a Jewish literate class, and stretches across cultural and ethnic groupings from Egypt to Mesopotamia), and finds no correlation of it among popular Jewish culture before the second century c.e.:

Nevertheless, to make an argument that a specific theme belongs to the earliest sources of the gospels is not sufficient to associate it with history. The interrelated themes that have brought Weiss and Schweitzer — and the scholarship following them — to speak of Jesus as an apocalyptic prophet do not reflect religious movements of the first century BCE. The thematic elements of a divinely destined era of salvation, a messianic fullness of time and a day of judgment bringing about a transformation of the world from a time of suffering to the joys of the kingdom are all primary elements of a coherent, identifiable literary tradition, centuries earlier than the gospels, well-known to us from the Bible and texts throughout the entire Near East. (p. 28)

There may also be some relevance here in Jon D. Levenson’s case that at least some not insignificant number of Jews in the Second Temple period coming to embrace a theology involving salvation through an atoning sacrifice of Isaac, as I have discussed in posts archived here.

This makes perfect sense if the gospel writers are trying to make a historical figure fit the Messianic expectations and some elements in his story simply don’t fit well. But it makes no sense at all if they are making him up or his story simply arose out of the expectations. If that were the case his story would fit the expectations very neatly and these awkward elements wouldn’t exist.

This is a repeat of the standard argument among the biblical studies faculties to establish the historicity of everything from the baptism of Jesus to his resurrection. The logical structure of the argument is elsewhere described as “the divine fallacy”. More formally it is listed among other fallacies as the fallacy of (personal) incredulity.”

N.T. Wright and other mainstream academics join with apologists in using this logic to prove the historicity of the resurrection on the basis that the “embarrassing” and “uncomfortable” and “awkward” fact is that mere untrustworthy women were the first witnesses.

To paraphrase the way it goes:

This makes perfect sense if the gospel writers are trying to speak honestly about the historical resurrection of Jesus and some elements in their story simply don’t fit well.

It makes no sense at all if the gospel writers are trying to make up a story about the resurrection.

If that were the case, they would never have said women were the first witnesses.

Everyone knew that women’s testimony was worthless in those days.

So it makes perfect sense if the gospel writers were writing about a historical event.

Others use the same logical fallacy to prove God, or creation science, or psychic powers:

How else can you explain this of that fact?

God/creationism/the tooth fairy are the only explanations that make sense of the evidence!

No other explanation makes any sense!

That such fallacious reasoning underpins so much of historical Jesus studies seems to escape notice surely can only be explained in the context of its cultural familiarity. (Trying to avoid slipping into the same fallacy here. :-/ )

(The original context of the summary cited here, by Tim O’Neill, can be found here.)

“F” is for “False Dilemma”

Image by BinJabreel (Is on Hiatus) via Flickr

(The original context of the summary cited here, by Tim O’Neill, can be found here.)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“N.T. Wright and other mainstream academics…”

Is N.T. “some stories are so odd that they may just have happened” Wright a mainstram academic? 😮

I think Wright is just a very learned apologist. Anyone who seriously considers that dead people got up and walked around Jerusalem (Matthew 27:52) has given up the right to being called a historian. But that’s just my a priori denial of the miraculous I suppose.

I do see some of his many many words cited in scholarly discussions so it seems he is taken seriously to some extent.

Maybe the description should be “evangelical scholar”? In fewer words but with all the appearance of trying to look very serious we do have such scholars even “proving” by “historical method” the historicity of the miracles “reported” in Matthew and Josephus.

Plummer, Robert L: ‘Something awry in the Temple? the rending of the Temple veil and early Jewish sources that report unusual phenomena in the Temple around AD 30‘, Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 48 no 2 June 2005, p 301-316

About as mainstream as “it is certain — because it is impossible” Tertullian ever was 🙂

‘The idea that the stories about him are based on a historical figure is the most parsimonious explanation of how they arose….’

The Popeye defense.

The character of Popeye in the cartoons was based on a historical figure.

Therefore, Popeye existed.

‘He is mentioned by Josephus twice and by Tacitus once and the arguments required to make these clear references in two independent sources disappear require, once again, a small hill of suppositions and contrived arguments….’

The standard argument is that Jesus was such a nobody that contemporary Roman historians would never have written about him.

Yet Tacitus did not get his information from Christians, and is ‘independent’ evidence for the existence of ‘Christ’

All the historical Jesus scholars always go with this notion that Jesus and his followers were orthodox Jews and placed on Jesus the expectations of Messiahship. Why not at least look at the possibility that Jesus was a heretical Jew who was not understood by his disciples to be the Messiah because they were heretics looking for something other than the Messiah. Why couldn’t he have been a heretic walking around saying “I’m God, a higher God than the god that appeared to Moses.” This is very close to the presentation of Jesus in the gospel of John, and it is more likely historically (there’s more reason to put this kind of Jesus to death than an orthodox Jewish Jesus). Inasmuch as the Marcionites view Jesus in this sort of way and they were at least as early (if not earlier) than the Catholics, the allegiance of the historical Jesus scholars to Roman orthodoxy has made them utterly thoughtless and laughable in their ‘research.’

“This makes perfect sense if the gospel writers are trying to make a historical figure fit the Messianic expectations and some elements in his story simply don’t fit well. But it makes no sense at all if they are making him up or his story simply arose out of the expectations. If that were the case his story would fit the expectations very neatly and these awkward elements wouldn’t exist.”

I actually kind of agree with this paragraph. What it shows is that Marcionism and its gospel came first, in which Jesus WAS NOT the Messiah of the Jews. Then Judaizing revisers came along and forced into this the interpretation that he was the Messiah, and tried to make him an orthodoxish Jew. But by this time (for they, the Catholics, were the late-comers) the elements which didn’t fit the Messiah spin were too well known to be removed, so they had to stay.

In other words, these elements that don’t fit the Messiah story do show that somebody didn’t just say “I’m going to make a story about a Messiah” and then write the gospels. It is clear that before Jesus was made into a Messiah he was first understood to not be a Messiah of the Jews but only a God. The Messiah layer is added later.

Does this prove he really existed? no. But it proves that he wasn’t originally considered to be the Messiah. That part of our gospels is inauthentic and must be ignored as revisionism.

It is clear that before Jesus was made into a Messiah he was first understood to not be a Messiah of the Jews but only a God.

I don’t think it’s clear at all. I think it’s a possibility, but I don’t think it’s clear.

Frankly, I’ve started to wonder if it might be quite likely that the “Jesus of the Bible” is a composite figure from a lot of different religious sects, each of which saw him a different way. A Righteous Teacher, The Son of God, Jewish Messiah, Son of Man – and all of those different beliefs were forced together by the folks that Bart Ehrman calls the “proto-orthodox” in his books. Much like the later “Catholics” forced a variety of different views of Jesus’s divinity and cobbled together the Trinity from the disparate parts. If that’s the case, trying to find any kind of “historical Jesus” among the various bits and pieces might be a difficult if not impossible undertaking, since there might not be a single individual at the root of it all except the one that the proto-orthodox “created” to harmonize beliefs across the various sects of “Anointed”.

Its clear if you analyze the claims of prophecy fulfillment. Any Jewish child could debunk them with no effort. Isaiah 7 especially! Isaiah 8 tells us who the child born of a virgin was, because this ‘prophecy’ was fulfilled in Isaiah’s own lifetime–Jehovah himself points out the fulfillment to Isaiah, ‘call his name Mahershalalhashbaz….’ It is clear, therefore, that all the Messiah prophecy hoopla was added later by Gentiles pretending to be Jews and was not part of the original story. And the reason the proto-Orthodox or Catholics or whatever you want to call them had to be so vitriolic against Marcionism was because they (the proto-orthodox) were the new-comers and everybody knew it. That’s why they had to be such big loud-mouth Marcion bashers.

“Why couldn’t he have been a heretic walking around saying “I’m God, a higher God than the god that appeared to Moses.”

Because that means three thousand years of Christian history would have been based on a homeless guy from the Middle East with a mental illness.

…..oh, wait…..

“This makes perfect sense if the gospel writers are trying to make a historical figure fit the Messianic expectations and some elements in his story simply don’t fit well. But it makes no sense at all if they are making him up or his story simply arose out of the expectations. If that were the case his story would fit the expectations very neatly and these awkward elements wouldn’t exist.”

I actually think there is something here…

If the Jesus figure is nothing but a floating abstraction – completely devoid of any connection to historical events – then, surely, fitting such a figure into current messianic expectations and OT prophetic interpretations would have been a piece of cake for the gospel writers.

If, on the other hand, some historical person X is being viewed as somehow relevant to the early Christian message, understanding – and such a historical person X did not fit the expected messianic mold – then would not such a historical person X give the ‘orthodox’ position a very difficult job.

Not only a hard job fitting such a person into expectations – but to ‘sell’ such an un-orthodox messiah to a Jewish audience would be extremely difficult.

And is not such a thought evident when the gospel of Mark has Jesus saying the following:

“And he asked them, But who say ye that I am? Peter answereth and saith unto him, Thou art the Christ. And he charged them that they should tell no man of him. ”

An un-orthodox messiah, maybe even a non-Jewish, or a half-Jewish messiah, would never be accepted as fulfilling the expected messianic role.

If this was the situation faced by the early Christians – then the gospel Jesus figure is simply a model, a method (apart from any theological interests) that was the chosen framework to get a messianic message of ‘salvation’ into a Jewish culture – and later into the gentile world.

Why bother with OT prophecy at all – perhaps to give ‘roots’, to the christian origin story. Mythology, without being merged to prophetic interpretations, is an anytime, anywhere, structure. Early christians, for all the gnostic ideas, wanted to place their origins in real time.

(no ‘salvation’ in any human man of course – ‘salvation’ only in whatever meaningful ideas any human might come up with…)

But the fact remains that there was no general Jewish expectation of a messiah. Jewish ideas about what the messiah would be and what he would do were widely and wildly varied — and quite likely confined to the “literary chattering classes”.

In my next post I will be adding evidence from the Matthew nativity story that demonstrates the absence of any such widespread expectation.

I don’t see anything difficult for the writers of Matthew and Luke here. Old Testament models gave them plenty of precedents for how to construct a story that desired to get persons from place A to B and back again etc. And not only OT stories. Many of the popular “novellas” and similar of the era were essentially travelogue adventures.

I think we have heard these mantras so often — general Jewish expectations of a messiah, gospel authors going through hoops to reconcile Bethlehem and Nazareth — it’s all in our minds.

As for a prophecy-driven narrative, this was also standard fare of both Jewish and non-Jewish fiction of the time.

But I realize as I am writing this that your arguments (and my responses) are anticipating my next post in which I go into a little more detail.

If you are still not persuaded, have another go 🙂

Post script:

The apparent difficulties in the gospels are thought to have originated with Mark. Mark’s gospel is not unlike some of the more “gnostic” sounding gospels that apparently followed, such as the Gospel of Thomas. A common trope was the juxtaposition of ironies, opposites, syzygies, paradoxes. What the more gnostic type gospels did with sayings, Mark did in narrative form. The Messiah who dies, the binding exorcist who is bound and overcome, the called are blind and the uncalled crowds see, land of gentiles (galilee) responds while city of God is the centre of darkness, books have been written on all of these polarities in Mark, — the ancients, especially around this time and later, loved all this stuff, it seems. It is a spin-off from various philosophical thoughts, and seems to have had some attraction as a form of esoteric wisdom.

None of this is evidence of narrative difficulty. It is what the narrative is thriving on. It makes his Jesus mysterious. Someone only the wise can appreciate.

This is interpreting Mark in the light of the literature and thought that his narrative seems to echo. Once we go beyond this, I think we are assuming, say, historicity. Our suggestion that the author is facing a difficulty because of X or Y is to presume, then, a historical scenario for which we lack any evidence.

(Better get out of the way now- – your comments got me started 🙂

Neil, Don’t get me wrong here……Jesus is mythological – no question about that. However, that fact does not negate the relevance of the existence of an historical person X that was important to the ideas of those early christians..

No worries. I wasn’t thinking you were expressing anything like an historical or other Jesus. I suppose I just got a bit carried away with trying to cover what I thought might be some areas of my thoughts needing a bit more development. It’s a topic on my mind recently and I’m really thinking/typing “aloud” to work it all through. I hope I didn’t come across heavy at all — maybe too many words are too heavy. I might have misunderstood you to some extent, too. Thanks for letting me know.

Hi Neil

Re your comments on Wright. Evangelical scholar is a good description. He certainly knows his stuff. I’d probably put him in the same category as Ben Witherington. He’s a harmoniser.

I’m actually trying to do a Masters on the historical Jesus at the moment and Wright is one of historians I’m looking at (his doorstops are tiresome. Someone like Geza Vermes manages to say more in about half as much space). Alas, I don’t read Greek, so it’s more of a historigraphical study of secondary literature. I am working out of the premise that Jesus existed, although I have serious doubts. Admittedly, there are lots of bad ‘mythist’ stuff around the internet, but Doherty and Robert Price’s views seem very cogent. It’s also mildly depressing to see such brickbats tossed at people who question the existence of Jesus. One scholar, Mark Allen Powell, likened questioning Jesus’ historicity to denying the Holocaust, a candidate for possibly the worst historical analogy of all time.

Your comments on other ancient history are interesting. How would you compare the evidence for Jesus and say, Alexander the Great? Jesus scholars like to say the sources for Alexander are equally problematic. Be interested in your views.

Thanks for your time. Really glad I’ve discovered your blog

Well, you could call him “evangelical scholar” if you’re contrasting it to “critical scholar” or “real scholar” 😛

On comparing sources for Alexander I have written Comparing the sources a little while ago.

Also What Josephus might have said about the gospels.

(From my “Historiography” archive)

We also have primary evidence for Alexander. Coins. Inscriptions of various sorts.

I recently wrote something about this in the Richard Dawkins forum but cannot find it now– also showed how for Julius Caesar we have contemporary writings of known provenance (including writings of Julius Caesar himself); and for Socrates, similarly, we have contemporary reference in Aristophanes and writings of his students Plato and Xenophon. Someone replied that these were famous at the time and expected to be well sourced.

I replied to the effect that the gospels say Jesus was so famous people flocked in their thousands from Tyre, Syria, Jordan, to see and hear him, and he was forced to exit the cities for the crowds mobbing him all the time. In Acts Paul could be quoted as saying, when on trial, that none of this was done in a corner. Yet not one gospel author had the presence of mind to name a single on of his sources for verification. (I’m sure I’ve discussed Luke’s prologue in relation to this, too.)

P.S. — Bauckham also drew on the obscene parallel with the holocaust. I addressed his comparison in the several posts I did on his chapter 18.

Such analogies do demonstrate how deeply embedded in our psyches is the resistance to any radical criticism of one of our foundational and still powerful cultural icons.

Mythicism is regularly compared to creationism, and is refuted by declarations that many scholars have examined it, reviewed it and rejected it.

http://exploringourmatrix.blogspot.com/2010/01/review-of-doubting-jesus-resurrection.html

Have just read the exchanges between you and James McGrath. They began with the review of a book that looks to me like nothing but a detailed rationalization of a miracle story. Those who find themselves unable to doubt that there is something behind a miracle story — say the feeding of the 5000 — can reconcile their rationalist tendencies by finding psychological or whatever explanations to show how it began with one act of generosity which inspired everyone else to pull a few loaves out of their pockets. If it can be rationalized then we can claim to have found a “historical”! explanation for it!

This is just too depressing.

OK – here is another go…

I just had a quick look online re messianic idea around the gospel timeline.

Any thoughts on these?

Josephus: War 2:1

“But now, what did the most elevate them in undertaking this war, was an ambiguous oracle that was also found in their sacred writings, how,” about that time, one from their country should become governor of the habitable earth.” The Jews took this prediction to belong to themselves in particular, and many of the wise men were thereby deceived in their determination. Now this oracle certainly denoted the government of Vespasian, who was appointed emperor in Judea.””

(sure, Josephus was having no time for any flesh and blood Jewish Messiah – but found no problem with giving the ‘honor’ to Vespasian – maybe he had his eye on something else – and the non-Jew Vespasian was a handy red herring…..)

The Dead Sea Scrolls.

“..until the prophet comes, and the Messiahs of Aaron and Israel”

“until there arises the messiah of Aaron and Israel. He shall atone for their sins…”

“Until the messiah of justice comes, the branch of David.”

Philo:

The Life of Moses I:289-290: “There shall come forth from you one day a man, and he shall rule over many nations and his kingdom spreading every day shall be exalted on high”

“To Philo, the special theological role of the Jewish nation is central, both on the historical and the cosmic/universal level, as well as within the context of futuristic eschatology. The expectation of a messianic emperor is not as central, but it forms a natural and integral part of the thinking of Philo, since he emphasizes the role of Moses as king and entertains an ideology of kingship as part of the Jewish legislation. Accordingly, the concept of a future messianic emperor is not an alien element in his exegesis and in his expectations for the future.” (Borgen, “Reflections on Messianic Ideas in Philo”,.

Sure, purely intellectual pastimes were a luxury that few in those days would have been concerned with – but that there were those interested in such things – well, we do have the gospel storyline, we have Josephus and we have Philo – and the Dead Sea Scrolls. How all of these perceived what a messiah would be like is another matter – interpretations then, as today, are a dime a dozen….

…………..no edit button…

Reference for Josephus: War Book V1 ch.2.1

“But the fact remains that there was no general Jewish expectation of a messiah. Jewish ideas about what the messiah would be and what he would do were widely and wildly varied — and quite likely confined to the “literary chattering classes”.

In my next post I will be adding evidence from the Matthew nativity story that demonstrates the absence of any such widespread expectation.”

But that idea, ‘no general Jewish expectation of a messiah’, is surely besides the point! All intellectual innovation needs is for one spark plug to fire in one brain…

“But the fact remains that there was no general Jewish expectation of a messiah. Jewish ideas about what the messiah would be and what he would do were widely and wildly varied — and quite likely confined to the “literary chattering classes”.

Likely confinement (of wildly and widely varied ideas) would certainly “appear” to be the case with the limited surviving manuscripts of the ‘literary chattering classes’.

The ‘fact’ that there is no general expectation (particular and generally agreed upon?) , does not rule out particular or… or… ‘general’ expectations that are not “confined”.

I digress and ask rhetorically, “What is the “expectation” of ‘America’? Is it a Lincoln/Gettysburg last best hope of mankind? Is it a Manifest Destiny for popular economic expansion?

Does one have to be ‘literate’ to pick up or ‘volunteer’ to carry a pike or musket?

(Drifting further off topic with maryhelena’s spark plug (above)…

What after all is the use or need for literacy in a Stalinist or Hitlerite state, when it comes to ‘intellectual innovation’ in categories of Messianism or “America”?)

We know precious little about popular beliefs among early first century Judeans. All the more reason to appreciate what the evidence itself can and can’t tell us and to remain open to new insights that will revise what we think we know.