‘Parable’ is an English version of the Greek word parabolē. According to Aristotle (Rhetoric, 2.20) parables were used by orators in inductive or indirect proof as a generally recognized means of demonstration and illustration. They are, according to him, of two kinds: true events taken from history, and the more easily invented example such as the fable or the parables used by Socrates in Plato’s dialogues. Characteristically, he had a decided preference for the first of these as against the second with its allegorical form. It was a preference which was to appeal strongly and fatefully to modern critics such as Jülicher and Dodd who had had a classical education.

But the education of the New Testament writers was different. The Bible, not Aristotle, was their teacher and they possessed it in a Greek translation, the Septuagint. It was full of parables, and the Septuagint translation was usually careful to translate the Hebrew mashal by the Greek parabolē in spite of the extraordinary range of mashal. Since that range is so wide and contains a number of things which would not be called parables nowadays, it is worth setting it out with examples both for reference and as an historical corrective. (Drury, Parables in the Gospels, p. 8)

So what are sorts of things does Drury set out as instances of “mashal” or “parables” in the Old Testament? This is something worth knowing if the New Testament gospels do in fact mean any sort of OT-type “mashal” when they use the word “parable”. We see here in the literary world of the authors of the gospels what parables looked like and the purposes to which they were put. Drury identifies six types of parables:

- Sayings

- Figurative sayings or metaphors

- Enigmatic allegories

- Songs of derision

- Bywords

- Prophetic oracles

1. A Saying

Two examples:

2 Then Saul took three thousand chosen men out of all Israel, and went to seek David and his men upon the Rocks of the Wild Goats.

3 And he came to the sheepcotes by the way, where there was a cave; and Saul went in to relieve himself, and David and his men remained in the recesses of the cave.

4 And the men of David said unto him, “Behold the day of which the Lord said unto thee, ‘Behold, I will deliver thine enemy into thine hand, that thou mayest do to him as it shall seem good unto thee.’” Then David arose and cut off the skirt of Saul’s robe privily.

5 And it came to pass afterward that David’s heart smote him because he had cut off Saul’s skirt.

6 And he said unto his men, “The Lord forbid that I should do this thing unto my master, the Lord’S anointed, to stretch forth mine hand against him, seeing he is the anointed of the Lord.”

7 So David stayed his servants with these words, and suffered them not to rise against Saul. But Saul rose up out of the cave and went on his way.

8 David also arose afterward, and went out of the cave and cried after Saul, saying, “My lord the king.” And when Saul looked behind him, David stooped with his face to the earth and bowed himself.

9 And David said to Saul, “Why hearest thou men’s words, saying, ‘Behold, David seeketh thy hurt?’

10 Behold, this day thine eyes have seen how that the Lord had delivered thee today into mine hand in the cave, and some bade me kill thee. But mine eye spared thee, and I said, ‘I will not put forth mine hand against my lord, for he is the Lord’S anointed.’

11 Moreover, my father, see, yea, see the skirt of thy robe in my hand; for in that I cut off the skirt of thy robe and killed thee not, know thou and see that there is neither evil nor transgression in mine hand, and I have not sinned against thee; yet thou huntest my soul to take it.

12 The Lord judge between me and thee, and the Lord avenge me of thee; but mine hand shall not be upon thee.

13 As saith the proverb [mishal] of the ancients, ‘Wickedness proceedeth from the wicked.’ But mine hand shall not be upon thee.

Here the “parable” (mashal) is

- an old proverb

- not figurative or illustrative

- concerns relation of one’s inner character to one’s behaviour

- set in context of a historical narrative to give it its meaning

Ezekiel 12 (KJ21)

22 “Son of man, what is that proverb that ye have in the land of Israel, saying, ‘The days are prolonged, and every vision faileth’?

Again the “parable” (mashal) is

- an old proverb

- not figurative or illustrative

- set in context of a historical narrative to give it its meaning

This is background information for future posts where I will discuss the significance of these sorts of parables for Jesus in the gospels.

2. Figurative Saying or Metaphor

1 Samuel 10 (KJ21)

9 And it was so that, when he had turned his back to go from Samuel, God gave him another heart; and all those signs came to pass that day.

10 And when they came thither to the hill, behold, a company of prophets met him; and the Spirit of God came upon him, and he prophesied among them.

11 And it came to pass when all who knew him before saw that, behold, he prophesied among the prophets, then the people said one to another, “What is this that has come unto the son of Kish? Is Saul also among the prophets?”

12 And one of the same place answered and said, “But who is their father?” Therefore it became a proverb [mishal]: “Is Saul also among the prophets?”

13 And when he had made an end of prophesying, he came to the high place.

Ezekiel 18 (KJ21)

2 “What mean ye, that ye use this proverb concerning the land of Israel, saying: ‘The fathers have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge’?

3 As I live, saith the Lord God, ye shall not have occasion any more to use this proverb in Israel.

These parables

- are figurative

- apply to misbehaviour — are moralistic

- the parables are given points where they originated/ceased to be used

3. The Enigmatic Allegory

Here we move out of the popular realm of the commonplace, figurative or not, into a more professional world of skilled contrivance bordering on obfuscation. The difficult parable, the complicated riddle, appealed as such to those who enjoyed intellectual exercise for its own sake and as an appropriate genre for exploring the relation of God to the historical world when it is felt to be not obvious but puzzling. (p. 10)

These are the sorts of difficult parables that are understood only by the trained sages. It takes learning or wisdom to understand them by one’s own efforts: Proverbs 1

6 to understand a proverb and the interpretation, the words of the wise and their dark sayings.

Ecclesiasticus /Wisdom of Jesus Son of Sirach 39

[1] On the other hand he who devotes himself to the study of the law of the Most High will seek out the wisdom of all the ancients, and will be concerned with prophecies; [2] he will preserve the discourse of notable men and penetrate the subtleties of parables; [3] he will seek out the hidden meanings of proverbs and be at home with the obscurities of parables.

Some examples of these sorts of parables. The first is particularly long –

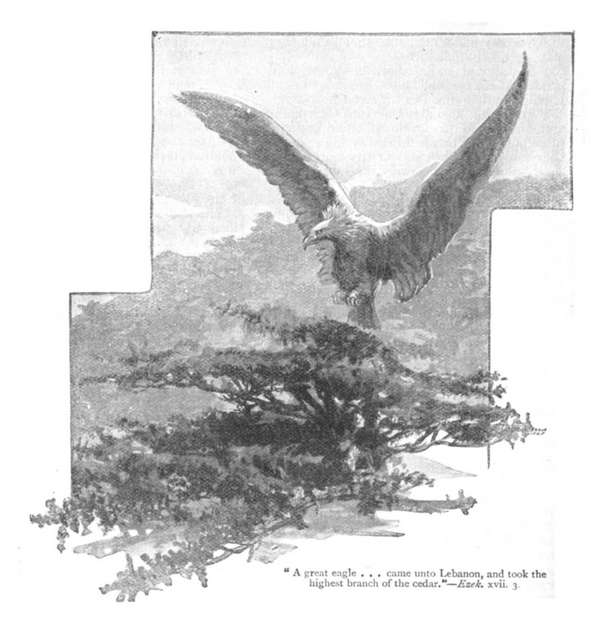

And the word of the Lord came unto me, saying,

2 “Son of man, put forth a riddle, and speak a parable unto the house of Israel,

3 and say, ‘Thus saith the Lord God: A great eagle [=Nebuchadnezzar King of Babylon] with great wings, longwinged, full of feathers which had divers colors, came unto Lebanon and took the highest branch of the cedar [=Judah’s king].

4 He cropped off the top of it young twigs and carried it into a land of traffic; he set it in a city of merchants [=Babylon].

5 He took also of the seed of the land and planted it in a fruitful field [=placed a new king, Zedekiah, over Judah]. He placed it by great waters and set it as a willow tree.

6 And it grew and became a spreading vine of low stature, whose branches turned toward him and the roots thereof were under him. So it became a vine, and brought forth branches and shot forth sprigs.

I am highlighting phrases to make it easier to skim over the parable while gathering the flow of its thought.

7 “‘There was also another great eagle [=Egypt’s Pharaoh] with great wings and many feathers; and behold, this vine did bend her roots toward him and shot forth her branches toward him, that he might water it by the furrows of her planting.

8 It was planted in a good soil by great waters, that it might bring forth branches and that it might bear fruit, that it might be a goodly vine.’

This parable is an allegory of the history of the nations set in Ezekiel’s day. The allegorical details are not natural. They are disconnected, implausible, fabulous, unrealistic. Eagles do not behave like gardeners and cedar twigs do not become spreading vines.

The events they symbolize are real enough, however, and are recognized behind the surreal metaphors.

9 Say thou, ‘Thus saith the Lord God: Shall it prosper? Shall he not pull up the roots thereof and cut off the fruit thereof, that it wither? It shall wither in all the leaves of her spring, even without great power or many people to pluck it up by the roots thereof.

10 Yea, behold, being planted, shall it prosper? Shall it not utterly wither when the east wind toucheth it? It shall wither in the furrows where it grew.’”

Now comes the explanation of the parable:

11 Moreover the word of the Lord came unto me, saying,

12 “Say now to the rebellious house: ‘Know ye not what these things mean?’ Tell them: ‘Behold, the king of Babylon is come to Jerusalem, and hath taken the king thereof and the princes thereof, and led them with him to Babylon;

13 and hath taken of the king’s seed and made a covenant with him, and hath taken an oath from him. He hath also taken the mighty of the land,

14 that the kingdom might be base, that it might not lift itself up, but that by keeping of his covenant it might stand.

15 But he rebelled against him in sending his ambassadors into Egypt, that they might give him horses and many people. Shall he prosper? Shall he escape that doeth such things? Or shall he break the covenant and be delivered?

16 As I live, saith the Lord God, surely in the place where the king dwelleth that made him king, whose oath he despised and whose covenant he broke, even with him in the midst of Babylon he shall die.

17 Neither shall Pharaoh with his mighty army and great company help him in the war, by casting up siege mounds and building forts to cut off many persons.

18 Seeing he despised the oath by breaking the covenant, when, lo, he had given his hand and hath done all these things, he shall not escape.

19 Therefore thus saith the Lord God: As I live, surely Mine oath that he hath despised and My covenant that he hath broken, even it will I recompense upon his own head.

20 And I will spread My net upon him, and he shall be taken in My snare, and I will bring him to Babylon and will plead with him there for his trespass that he hath trespassed against Me.

21 And all his fugitives with all his troops shall fall by the sword, and they that remain shall be scattered toward all winds; and ye shall know that I, the Lord, have spoken it.

22 “‘Thus saith the Lord God: I will also take of the highest branch of the high cedar, and will set it; I will crop off from the top of his young twigs a tender one, and will plant it upon a high mountain and eminent.

23 In the mountain of the height of Israel will I plant it; and it shall bring forth boughs and bear fruit and be a goodly cedar, and under it shall dwell all fowl of every wing; in the shadow of the branches thereof shall they dwell.

24 And all the trees of the field shall know that I, the Lord, have brought down the high tree, have exalted the low tree, have dried up the green tree, and have made the dry tree to flourish. I, the Lord, have spoken and have done it.’”

Such mishalim or parables are allegorical tales of political or historical events. They symbolize history. We will see the significance of this precedent (parables being used to convey historical events as a hidden mystery) when we come to the parables of Jesus.

Drury adds here a comparison with the dream of Pharaoh in Genesis 41 which foretold the ensuing fourteen years of history for the region.

As enigmatic symbols they appropriately come through divine revelation, usually in visions or dreams, to a prophet of God.

The are intended to be enigmatic: an interpreter is always necessary to explain them.

Here are the beginnings of that apocalyptic vision of history which resolves its moral contradictions by resort to a divine elsewhere, where alone sense is to be found. The interpreter is the connection between the two. (p. 13)

4. Song of Derision

4 that thou shalt take up this proverb [mashal, though here the Septuagint uses thrēnos] against the king of Babylon, and say: “How hath the oppressor ceased! The golden city ceased!

5 The Lord hath broken the staff of the wicked and the scepter of the rulers.

6 He who smote the people in wrath with a continual stroke, he that ruled the nations in anger, is persecuted, and none hindereth.

7 The whole earth is at rest and is quiet; they break forth into singing.

8 Yea, the fir trees rejoice at thee, and the cedars of Lebanon, saying, ‘Since thou art laid down, no hewer has come up against us.’

9 Hell from beneath is moved for thee to meet thee at thy coming; it stirreth up the dead for thee, even all the chief ones of the earth; it hath raised up from their thrones all the kings of the nations.

10 All they shall speak and say unto thee: ‘Art thou also become weak as we? Art thou become like unto us?’

11 Thy pomp is brought down to the grave, and the noise of thy viols; the worm is spread under thee, and the worms cover thee.

12 “How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer/Day Star, son of the morning! How art thou cut down to the ground, who didst weaken the nations!

13 For thou hast said in thine heart, ‘I will ascend into heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God; I will sit also upon the mount of the congregation, in the sides of the north.

14 I will ascend above the heights of the clouds; I will be like the Most High.’

15 Yet thou shalt be brought down to hell, to the sides of the pit.

16 They that see thee shall narrowly look upon thee and consider thee, saying, ‘Is this the man that made the earth to tremble, that did shake kingdoms,

17 that made the world as a wilderness and destroyed the cities thereof, that opened not the house of his prisoners?’

18 All the kings of the nations, even all of them, lie in glory, every one in his own house.

19 But thou art cast out of thy grave like an abominable branch, and as the raiment of those that are slain, thrust through with a sword, that go down to the stones of the pit, as a carcass trodden under feet.

20 Thou shalt not be joined with them in burial, because thou hast destroyed thy land and slain thy people. The seed of evildoers shall never be renowned.

21 Prepare slaughter for his children for the iniquity of their fathers, that they do not rise, nor possess the land, nor fill the face of the world with cities.”

Trees are symbolic of kingdoms; a falling star is symbolic of the city of Babylon’s fall.

This is how parables work, what they do. They are historical symbols.

Habakkuk 2

6 Shall not all these take up a parable against him, and a taunting proverb against him, and say, ‘Woe to him that increaseth that which is not his (how long?) and to him that ladeth himself with thick clay’?

7 Shall they not rise up suddenly that shall bite thee, and awake, that shall vex thee? And shalt thou be for booty unto them?

8 Because thou hast despoiled many nations, all the remnant of the people shall despoil thee, because of men’s blood, and for the violence of the land, of the city, and of all that dwell therein.

Micah 2

4 In that day shall one take up a parable against you, and lament with a doleful lamentation and say, ‘We are utterly despoiled; He hath changed the portion of my people. How hath He removed it from me! Turning away, He hath divided our fields.’”

These mishalim/parables are taunts directed at future events when history will be climaxed with the fall of great oppressors.

5. Byword

In this instance it is the audience (an individual or a nation) who will become the parable, a byword, as a lesson to others. Again, history and parable go hand in hand.

Deuteronomy 28

37 And thou shalt become an astonishment, a proverb, and a byword among all nations whither theLord shall lead thee.

Psalm 44

14 Thou makest us a byword among the heathen, a shaking of the head among the people.

Psalm 69

11 I also made sackcloth my garment, and I became a proverb to them.

2 Chronicles 7

20 then will I pluck them up by the roots out of My land which I have given them; and this house which I have sanctified for My name will I cast out of My sight, and will make it to be a proverb and a byword among all nations.

Tobit 3

4 thou hast delivered us for a spoil, and unto captivity, and unto death, and for a proverb of reproach to all the nations among whom we are dispersed.

These parables are the righteous one who suffers or the sinner who is shamed and without hope. There is no answer for their plight except from God.

6. Prophetic Oracle

Here we find only one instance, Drury informs us, and that is the oracles Balaam proclaimed of Israel’s future: Numbers 23 and 24. Again Drury alerts us to the significant features:

- the historical context, with the vision of history as directed by God

- it comes from via a divine messenger to a prophet

- in this case the vision or message has an effect on the prophet himself.

-o-O-o-

What is a parable?

In reviewing these six forms of parables Drury identifies what he sees as the single, primary element that characterizes the parable:

It describes a distillation of historical experience into a compact instance which is usually figurative and remains strongly embedded in its narrative matrix. (p. 15, italics original, bolding mine)

-o-O-o-

Three “related” forms

Drury then classifies three other types of composition that he sees as not strictly of the same kind but “closely related to the parable”. I have some difficulty grasping exactly why Drury classifies these three as only “related” to the parable and Drury himself refers to boundaries in literature not always being very distinct. So for sake of completeness here are those three:

First, the prophets often used figurative or allegorical methods to make their sort of historical critical points (Drury stresses these are the messages of prophets (“their…points”) as distinct from directly sourced divine wisdom) —

Here we have what Drury has posited are precursors to the “Enigmatic Allegory” form of parable above:

2 Samuel 12

And the Lord sent Nathan unto David. And he came unto him, and said unto him, “There were two men in one city, the one rich and the other poor.

2 The rich man had exceeding many flocks and herds.

3 But the poor man had nothing, save one little ewe lamb, which he had bought and nourished up. And it grew up together with him and with his children; it ate of his own meat and drank of his own cup, and lay in his bosom, and was unto him as a daughter.

4 And there came a traveler unto the rich man, and he was unwilling to take of his own flock and of his own herd to dress for the wayfaring man who had come unto him, but took the poor man’s lamb and dressed it for the man who had come to him.”

5 And David’s anger was greatly kindled against the man, and he said to Nathan, “As the Lord liveth, the man who hath done this thing shall surely die.

6 And he shall restore the lamb fourfold, because he did this thing and because he had no pity.”

7 And Nathan said to David, “Thou art the man. Thus saith the Lord God of Israel: ‘I anointed thee king over Israel, and I delivered thee out of the hand of Saul,

8 and I gave thee thy master’s house and thy master’s wives into thy bosom, and gave thee the house of Israel and of Judah; and if that had been too little, I would moreover have given unto thee such and such things.

9 Why hast thou despised the commandment of the Lord, to do evil in His sight? Thou hast killed Uriah the Hittite with the sword, and hast taken his wife to be thy wife, and hast slain him with the sword of the children of Ammon.

10 Now therefore the sword shall never depart from thine house, because thou hast despised Me and hast taken the wife of Uriah the Hittite to be thy wife.’ . . . ”

This parable is given to trap David into an admission of guilt. Another parable that appeared on the surface to be an idyllic love song about a vineyard was also a trap set to convict the audience of sin: Isaiah 5

Now will I sing to my Well-beloved a song of my Beloved concerning His vineyard: my Well-beloved hath a vineyard on a very fruitful hill.

2 And He fenced it, and gathered out the stones thereof, and planted it with the choicest vine; and built a tower in the midst of it, and also made a wine press therein. And He looked for it to bring forth grapes, and it brought forth wild grapes.

3 “And now, O inhabitants of Jerusalem and men of Judah, judge, I pray you, between Me and My vineyard.

4 What could have been done more to My vineyard than I have not done in it? Why, when I looked for it to bring forth good grapes, brought it forth wild grapes?

5 “And now, I will tell you what I will do to My vineyard: I will take away the hedge thereof, and it shall be eaten up; and break down the wall thereof, and it shall be trodden down.

6 And I will lay it waste; it shall not be pruned nor dug, but there shall come up briers and thorns. I will also command the clouds that they rain no rain upon it.”

7 For the vineyard of the Lord of hosts is the house of Israel, and the men of Judah, His pleasant plant. And He looked for judgment, but behold, oppression; for righteousness, but behold, a cry.

Other examples include Hosea’s drama of the prophet’s marriage to a prostitute and Ezekiel’s allegory of Israel’s whoredom and adultery in chapters 16 and 23.

Second, parables have been noticed to have a riddling character, being virtually synonymous with riddles at Ecclesiasticus 39.3 and 47.15. —

Judges 14

14 And he [Samson] said unto them, “Out of the eater came forth meat, and out of the strong came forth sweetness.”

Third, there are fables.

Judges 9

7 And when they told it to Jotham, he went and stood on the top of Mount Gerizim, and lifted up his voice and cried, and said unto them, “Hearken unto me, ye men of Shechem, that God may hearken unto you.

8 The trees went forth once to anoint a king over them; and they said unto the olive tree, ‘Reign thou over us.’

9 But the olive tree said unto them, ‘Should I leave my fatness, withwhich by me they honor God and man, and go to be promoted over the trees?’

10 And the trees said to the fig tree, ‘Come thou, and reign over us.’

11 But the fig tree said unto them, ‘Should I forsake my sweetness and my good fruit, and go to be promoted over the trees?’

12 Then said the trees unto the vine, ‘Come thou, and reign over us.’

13 And the vine said unto them, ‘Should I leave my wine, which cheereth God and man, and go to be promoted over the trees?’

14 Then said all the trees unto the bramble, ‘Come thou, and reign over us.’

15 And the bramble said unto the trees, ‘If in truth ye anoint me king over you, then come and put your trust in my shadow; and if not, let fire come out of the bramble and devour the cedars of Lebanon.’

2 Kings 14

9 And Jehoash the king of Israel sent to Amaziah king of Judah, saying, “The thistle that was in Lebanon sent to the cedar that was in Lebanon, saying, ‘Give thy daughter to my son for a wife.’ And there passed by a wild beast that was in Lebanon, and trod down the thistle.

-o-O-o-

Two major features

Two major features of Old Testament parables have emerged from the survey: the imaginative use of figures and disguises together with a tight fit in the narrative setting. (p. 17)

Drury’s emphasis on integration with the narrative setting is important for the main thesis which is to argue that the parables in the gospels were the literary inventions of the evangelists. That’s something I hope to look at more closely in another post.

Ezekiel’s collection and contribution

All six forms of parables are found in Ezekiel.

- Sayings (unfigurative): 12:21-22

- Figurative sayings: 16:44; 18:2-3

- Elaborate historical allegories: chapters 15 and 17 (said to be incomprehensible at 20:49)

- The person’s actions: 24:3-5 (cooking in rusty pot); 24:15ff (death of his wife) . . . . — Ezekiel himself is a parable in a variety of ways.

- Songs of derision: chapters 27-28; 31-32 (laments over Tyre and Egypt)

- Prophetic oracles: passim

We will not meet a single book with the same range of parables until the gospels appear.

Indeed, Drury sees Ezekiel as a significant shaper of the parable tradition that will journey eventually into the gospels. The major feature of Ezekiel’s parables (one that will significantly flavour the parables in the gospels) is

his use of comparative figures in complex allegories which have a determinative historical context. (p. 18, my bolding)

Anyone wanting a tidy line of coherent thought in Ezekiel’s parables will be frustrated. He is quite capable of changing his symbols in a parable such as in chapter 19 where

- at one moment Israel is a lioness whose cubs were stolen

- and then in another is a vine that provided wood for a royal sceptre and is then withered

- and then, though earlier said to be dead, it is transplanted to a desert and burned.

The reason for these contortions is to make a symbolic tale fit all the details of history that he wants to address. In this case he is describing symbolically the captivities at the hands of the Egyptians and Babylonians, then the establishment and fate of Zedekiah as puppet king, and finally the exile of Judah to Babylon.

Similarly the city of Tyre is addressed first as a shipwreck and secondly as a fallen angel. Egypt is at one time a felled cedar tree and another as a stranded sea monster.

Ezekiel’s interpretation of the valley of dry bones also contains a significant feature. The angelic or spirit interpreter explains what the vision means but there’s a problem. His explanation does not exactly fit the details of the vision. In the vision the bones were scattered across the surface of the land. The interpretation, however, speaks of God opening the graves to raise up the bones.

This is not an indication of a later or extraneous origin for the interpretation, but rather that in interpretation creative activity goes on, adorning and amplifying the parable as it does so. This should be borne in mind when we come to similar gospel parables such as the sower where efforts have been made to separate parable from interpretation. Here is a big precedent for their belonging together, and it is not the only one in Ezekiel. (p. 19, italics original)

We see parable and its interpretation again merge into one in the allegory of the sheep and the shepherds in chapter 34 with its message of divine judgment. In the interpretation of this parable we read of God bringing his “sheep” out of the “diaspora among ‘peoples and countries'”. The symbol and the interpretation are once again fused.

[Ezekiel] was the father of apocalyptic, that ultimate biblical solution to enigmatic history which lives on allegory. He was also the father of the allegorical historical parable which is the commonest kind of parable in the Gospels. (p. 20)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Thanks a lot, Neil. That’s very interesting.