In a recent comment, Giuseppe asked about Mark 8:27-30 (the Confession at Caesarea Philippi). At issue is a grammatical error in the text, mentioned in Robert M. Price‘s Holy Fable Volume 2, but first (apparently) noticed by Gerd Theissen in The Miracle Stories of the Early Christian Tradition. Both Theissen and Price argue that the error reveals a redactional seam in Mark’s gospel. Beyond that, Giuseppe suggests that the original text beneath or behind the existing text of Mark indicates that Peter confessed that Jesus was the Marcionite Christ, not the Jewish Messiah.

Lost in the weeds

I confess that I ruminated over the text in question for quite some time before I understood exactly what Theissen and Price were getting at. One can easily get lost in the weeds here, so I’ll try to break it down into small steps.

To begin with, we have two passages in Mark in which we find lists of possible identities for Jesus. The first happens when Herod Antipas hears about Jesus and thinks it must be John the Baptist raised from the dead.

14 King Herod heard of it, for Jesus’ name had become known. Some were saying, “John the baptizer has been raised from the dead; and for this reason these powers are at work in him.”

15 But others said, “It is Elijah.” And others said, “It is a prophet, like one of the prophets of old.”

16 But when Herod heard of it, he said, “John, whom I beheaded, has been raised.”

(Mark 6:14-16, NRSV)

The second happens just before Peter’s confession.

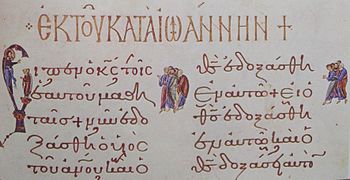

27 And Jesus went out, and his disciples, into the towns of Caesarea Philippi: and by the way he asked his disciples, saying unto them, Whom do men say that I am?

28 And they answered, John the Baptist; but some say, Elias; and others, One of the prophets.

29 And he saith unto them, But whom say ye that I am? And Peter answereth and saith unto him, Thou art the Christ.

30 And he charged them that they should tell no man of him.

(Mark 8:27-30, KJV)

John the Who?

I chose the NRSV for the first passage, because it stays very close to the original Greek, even to the point of “John the baptizer” vs. “John the Baptist.” In 6:14, we find the word βαπτίζων (baptizōn), the present participle. Put simply, the literal text would be something like “John, the Baptizing One.” (Note: this word, used as an appositive after John’s name, is found only in Mark’s gospel. The author of the fourth gospel uses it, but only as a participle describing an activity.)

On the other hand, in 8:28, Mark used a different word: βαπτιστήν (baptistēn), a noun in the accusative case. The NRSV helpfully gives us a verbal cue that something is different here by translating it as “John the Baptist,” which differs from the translation in 6:14. Unfortunately, the NRSV used “who” instead of “whom” in 8:27, so I went with the KJV there instead.

For our purposes here we need to know that at Caesarea Philippi, Jesus asks a question with an accusative “whom?” — τίνα (tina) — and so the answers need to be in the accusative as well. The point upon which Theissen builds his case will depend our understanding this error. In a stilted, word-for-word translation, we have something like: “Whom do the men pronounce me to be?” The words “whom” and “me” are in the objective (accusative) case; and in proper Greek, the answers should follow suit.

Two lists

The people haven’t figured out who Jesus is. They provide three wrong guesses. We see them listed in 8:28 — Continue reading “A Redactional Seam in Mark 8:28?”