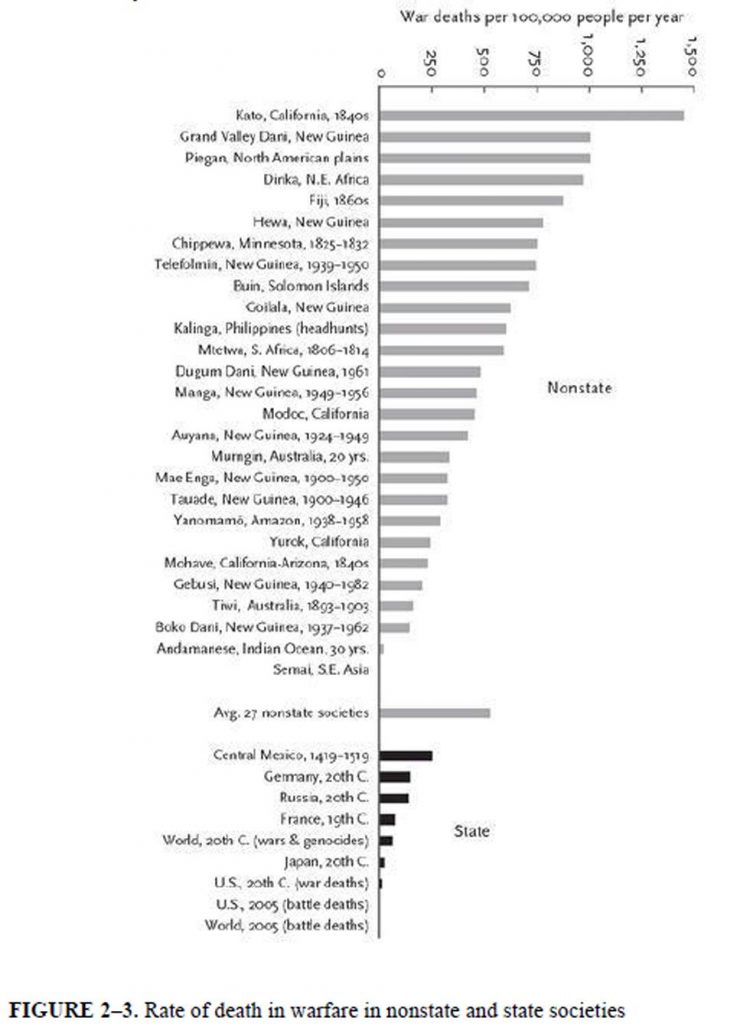

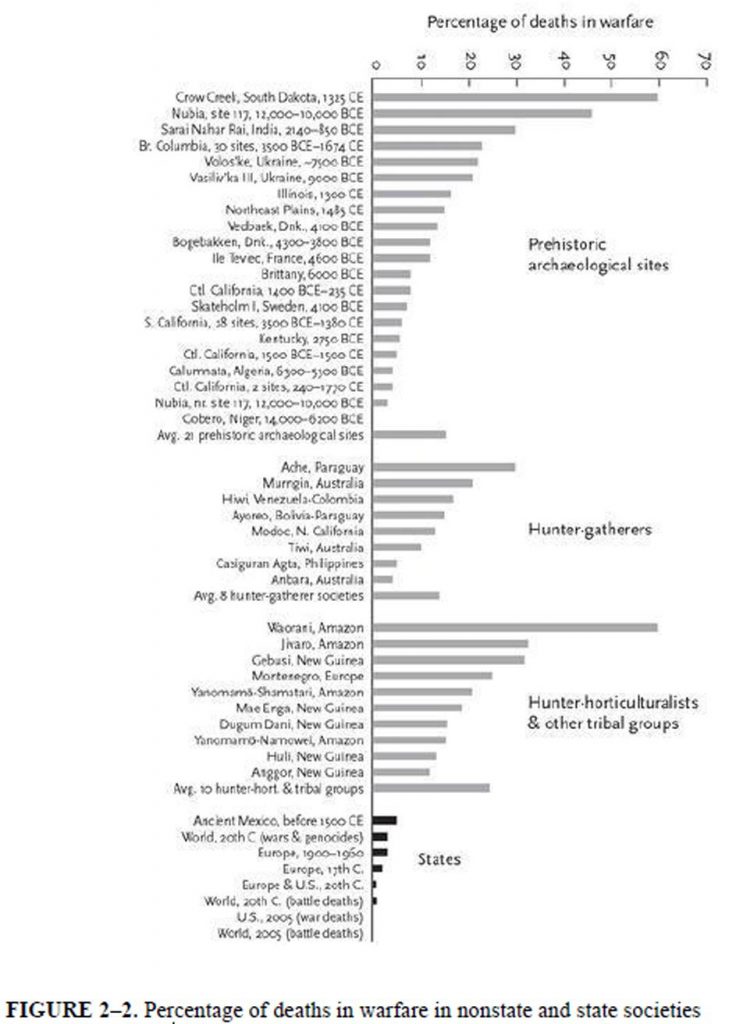

Thus concludes Stephen Pinker in The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (2012). He supplies tables to illustrate his point (click on the images to read larger text):

|

|

Pinker concludes from the above statistics that concerning warfare there has been a historical “retreat from violence”. Over millennia our species has transitioned

from the anarchy of the hunting, gathering, and horticultural societies in which our species spent most of its evolutionary history to the first agricultural civilizations with cities and governments, beginning around five thousand years ago. With that change came a reduction in the chronic raiding and feuding that characterized life in a state of nature and a more or less fivefold decrease in rates of violent death. I call this imposition of peace the Pacification Process.

But there is a problem.

Still, there are many ways to look at the data—and quantifying the definition of a violent society. A study in Current Anthropology published online October 13 acknowledges the percentage of a population suffering violent war-related deaths—fatalities due to intentional conflict between differing communities—does decrease as a population grows. At the same time, though, the absolute numbers increase more than would be expected from just population growth. In fact, it appears, the data suggest, the overall battle-death toll in modern organized societies is exponentially higher than in hunter–gatherer societies surveyed during the past 200 years.

Stetka, Bret. 2017. “Steven Pinker: This Is History’s Most Peaceful Time–New Study: ‘Not So Fast.’” Scientific American. November 9, 2017. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/steven-pinker-this-is-historys-most-peaceful-time-new-study-not-so-fast/. (Bolded highlighting is my own in all quotations.)

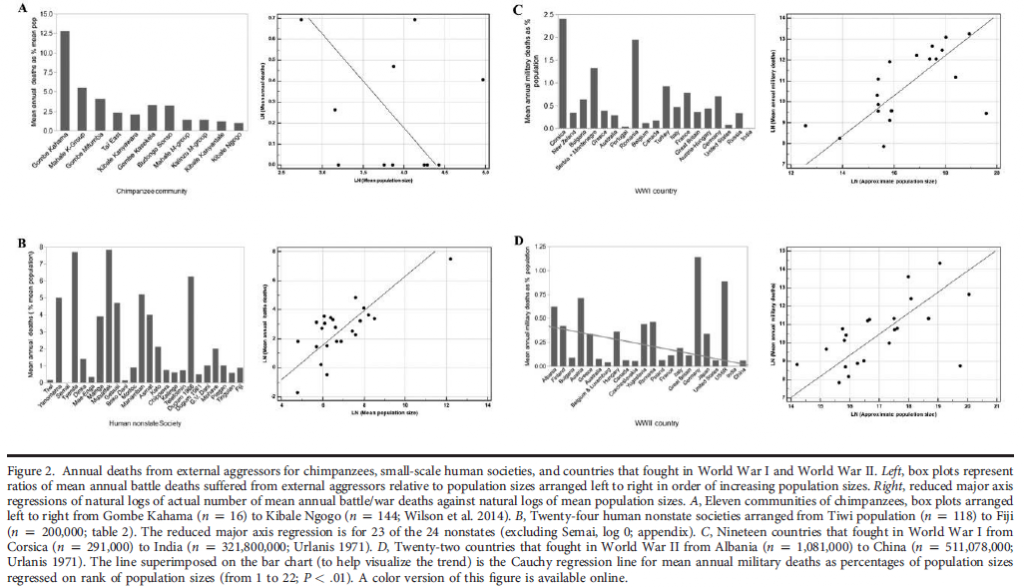

Here is some detail from that Current Anthropology study by Dean Falk and Charles Hildebot.

The objection raised by Stetka above is that Pinker overlooks the scaling factor when he interprets the raw statistics.

Psychologist Steven Pinker suggests that humans “started off nasty and . . . the artifices of civilization have moved us in a noble direction” (Pinker 2011:xxii). Figure 1 [Figure 2-2 above], reproduced from Pinker, illustrates his main evidence for asserting that states are less violent than small-scale “hunting, gathering, and horticultural societies in which our species spent most of its evolutionary history” (Pinker 2011:xxiv); however, because this figure depicts annual rates of war deaths suffered per 100,000 people, these ratios are blind to actual population sizes. (Falk and Hildebot)

By factoring in population sizes, F&H observe that the numbers of war deaths have increased exponentially as populations increase. Their studies were based on direct war or inter-group conflict deaths relative to population sizes of

- 11 chimpanzee communities,

- 24 human nonstates,

- 19 and 22 countries that fought in World War I and World War II.

Clicking on the following F&H image will enlarge it to allow for clearer detail:

The chimpanzees make an interesting comparison. Chimpanzee communities engage in deadly violence against one another but the numbers of absolute deaths suffered are unrelated to the sizes of their communities.

A Cochran-Armitage trend test indicates that, as mean chimpanzee population sizes increase, the percentages of mean annual deaths from external aggressors that are observed, inferred, or suspected decrease . . . . A reduced major axis regression . . . shows that the absolute number of annual deaths suffered by a population is unrelated to its size . . . .

To come full circle, assertions that humans living in states have become less violent than those living in nonstates, with the assertions being based on blind ratios of annual war deaths relative to population sizes (e.g., war deaths per 100,000 people), are parallel to the untenable assertion that squirrel monkeys are smarter than humans because they have relatively large (blind) ratios of brain sizes divided by body sizes. (F&H)

Are state societies less war-mongering than nonstate societies?

[N]onstates should be viewed as neither more nor less fundamentally violent than the countries that fought in World War I and World War II, because severity of war deaths scales nearly identically with population sizes in all three groups.

The more severe the anticipated casualties in a war the less frequent war occurs.

. . . thus, in 97 interstate wars that occurred between 1820 and 1997, “a 10-fold increase in war severity [war casualties] decrease[d] the probability of war by a factor of 2.6” (Cederman 2003:136; fig. 3). Importantly, wars causing relatively few absolute numbers of deaths occurred frequently; those with moderate deaths occurred less often; and highly disastrous wars (e.g., World War I and World War II) occurred rarely (fig. 3). . . . .

F&H cite other studies that conclude the likelihood of a third “rare” world war is “a distinct possibility” (because decisions to wage war are found to “[depend largely] on innovations in military technology and logistics and alterations in contextual conditions”) . . .

This is especially so because the onerous liability of weapons of mass destruction has failed to obviate further developments in war technology

The relative periods of peace between “rare major wars” is a sign of how extremely severe the next such war will be rather than a hopeful sign that we have become less violent somehow.

. . . not that larger populations are less prone to violence than smaller ones; rather, larger communities are less vulnerable to having large portions of their populations killed by (or entirely wiped out by) external enemies compared with smaller ones (i.e., there is safety in numbers). . . .

. . . people living in small-scale societies are not inherently more violent that those living in “civilized” states. Our analyses demonstrate that war deaths scale similarly with population sizes across all levels of human society.

Other scholars have uncovered the same results:

Based on our results, we conclude that trends in proportions of war group size or casualties in relationship to population are, in fact, described by deeper scaling laws driving group social organization subject to contingencies, such as logistical constraints, expedient needs, and technology. . . .

Indeed, while the probability of being involved in conflict as a member of a war group or as a casualty of conflict in large and/or contemporary societies is lower than in small-scale societies, it might not be driven by any better or worse angels of our nature. This probability might merely be an emergent outcome of differential logistical constraints and group populations. This probability may also change rapidly based on group conflict needs, expedience, and contingency. The demographic investment of any society in its own conflict issues or the lethality of any conflict then is not a matter of proportions but of scale. (Oka et al.)