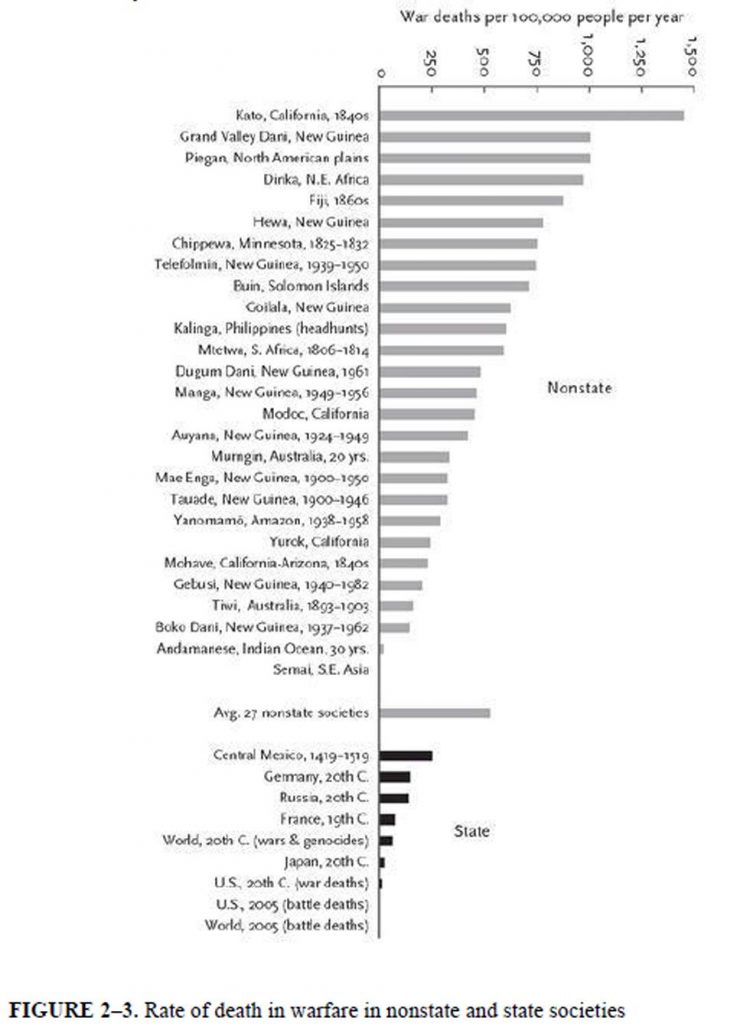

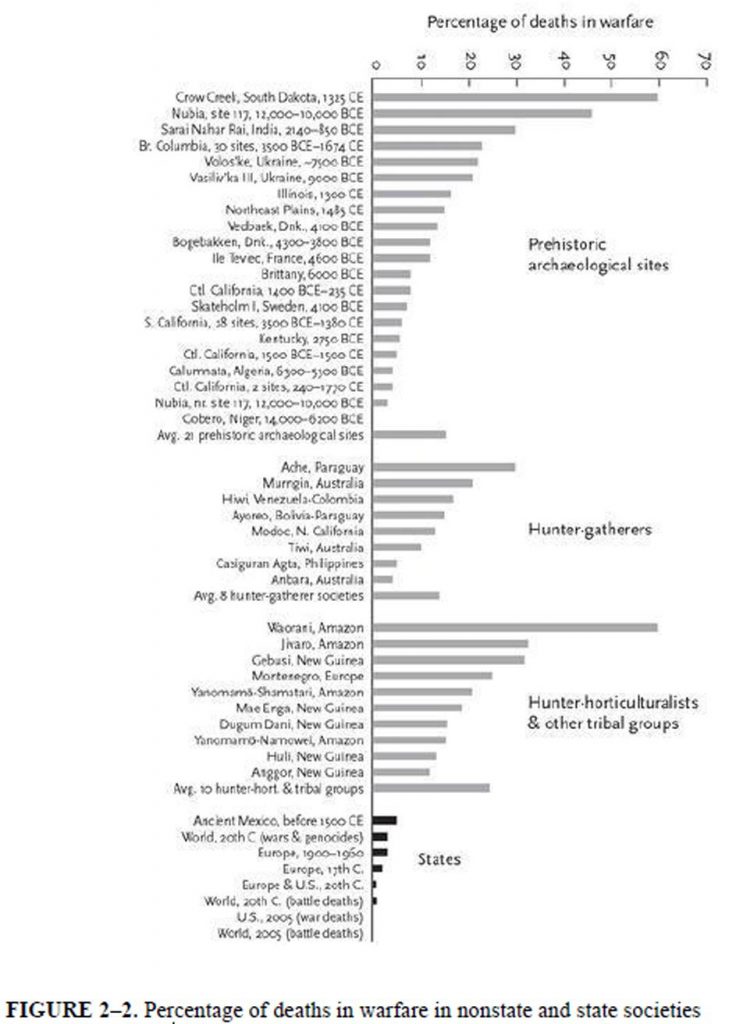

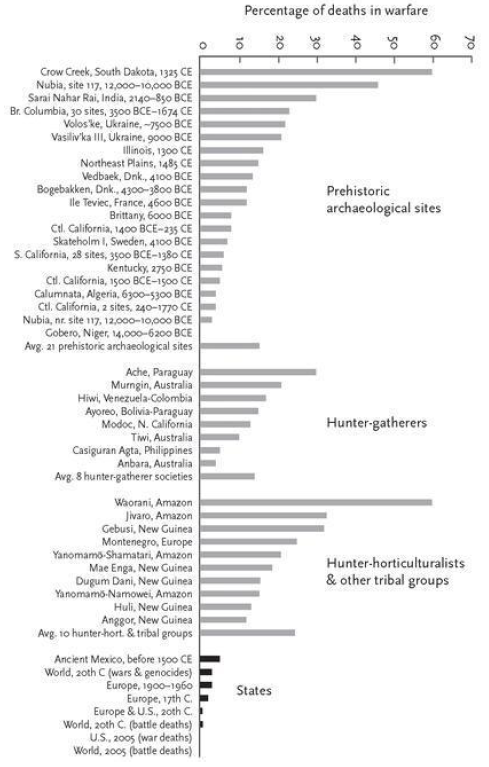

Thus concludes Stephen Pinker in The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (2012). He supplies tables to illustrate his point (click on the images to read larger text):

|

|

Pinker concludes from the above statistics that concerning warfare there has been a historical “retreat from violence”. Over millennia our species has transitioned

from the anarchy of the hunting, gathering, and horticultural societies in which our species spent most of its evolutionary history to the first agricultural civilizations with cities and governments, beginning around five thousand years ago. With that change came a reduction in the chronic raiding and feuding that characterized life in a state of nature and a more or less fivefold decrease in rates of violent death. I call this imposition of peace the Pacification Process.

But there is a problem.

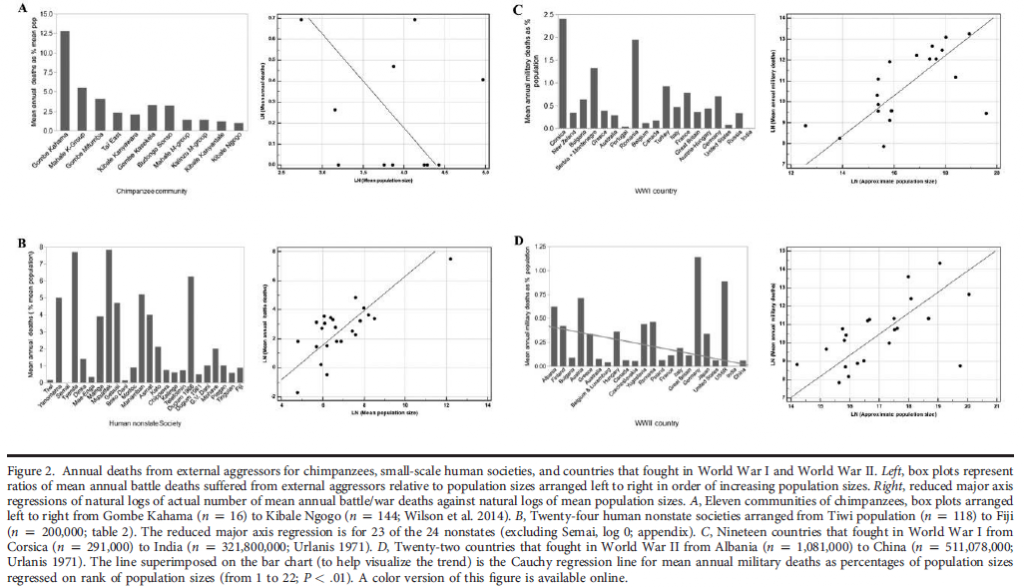

Still, there are many ways to look at the data—and quantifying the definition of a violent society. A study in Current Anthropology published online October 13 acknowledges the percentage of a population suffering violent war-related deaths—fatalities due to intentional conflict between differing communities—does decrease as a population grows. At the same time, though, the absolute numbers increase more than would be expected from just population growth. In fact, it appears, the data suggest, the overall battle-death toll in modern organized societies is exponentially higher than in hunter–gatherer societies surveyed during the past 200 years.

Stetka, Bret. 2017. “Steven Pinker: This Is History’s Most Peaceful Time–New Study: ‘Not So Fast.’” Scientific American. November 9, 2017. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/steven-pinker-this-is-historys-most-peaceful-time-new-study-not-so-fast/. (Bolded highlighting is my own in all quotations.)

Here is some detail from that Current Anthropology study by Dean Falk and Charles Hildebot.

The objection raised by Stetka above is that Pinker overlooks the scaling factor when he interprets the raw statistics.

Psychologist Steven Pinker suggests that humans “started off nasty and . . . the artifices of civilization have moved us in a noble direction” (Pinker 2011:xxii). Figure 1 [Figure 2-2 above], reproduced from Pinker, illustrates his main evidence for asserting that states are less violent than small-scale “hunting, gathering, and horticultural societies in which our species spent most of its evolutionary history” (Pinker 2011:xxiv); however, because this figure depicts annual rates of war deaths suffered per 100,000 people, these ratios are blind to actual population sizes. (Falk and Hildebot)

By factoring in population sizes, F&H observe that the numbers of war deaths have increased exponentially as populations increase. Their studies were based on direct war or inter-group conflict deaths relative to population sizes of

- 11 chimpanzee communities,

- 24 human nonstates,

- 19 and 22 countries that fought in World War I and World War II.

Clicking on the following F&H image will enlarge it to allow for clearer detail:

The chimpanzees make an interesting comparison. Chimpanzee communities engage in deadly violence against one another but the numbers of absolute deaths suffered are unrelated to the sizes of their communities.

A Cochran-Armitage trend test indicates that, as mean chimpanzee population sizes increase, the percentages of mean annual deaths from external aggressors that are observed, inferred, or suspected decrease . . . . A reduced major axis regression . . . shows that the absolute number of annual deaths suffered by a population is unrelated to its size . . . .

To come full circle, assertions that humans living in states have become less violent than those living in nonstates, with the assertions being based on blind ratios of annual war deaths relative to population sizes (e.g., war deaths per 100,000 people), are parallel to the untenable assertion that squirrel monkeys are smarter than humans because they have relatively large (blind) ratios of brain sizes divided by body sizes. (F&H)

Are state societies less war-mongering than nonstate societies?

[N]onstates should be viewed as neither more nor less fundamentally violent than the countries that fought in World War I and World War II, because severity of war deaths scales nearly identically with population sizes in all three groups.

The more severe the anticipated casualties in a war the less frequent war occurs.

. . . thus, in 97 interstate wars that occurred between 1820 and 1997, “a 10-fold increase in war severity [war casualties] decrease[d] the probability of war by a factor of 2.6” (Cederman 2003:136; fig. 3). Importantly, wars causing relatively few absolute numbers of deaths occurred frequently; those with moderate deaths occurred less often; and highly disastrous wars (e.g., World War I and World War II) occurred rarely (fig. 3). . . . .

F&H cite other studies that conclude the likelihood of a third “rare” world war is “a distinct possibility” (because decisions to wage war are found to “[depend largely] on innovations in military technology and logistics and alterations in contextual conditions”) . . .

This is especially so because the onerous liability of weapons of mass destruction has failed to obviate further developments in war technology

The relative periods of peace between “rare major wars” is a sign of how extremely severe the next such war will be rather than a hopeful sign that we have become less violent somehow.

. . . not that larger populations are less prone to violence than smaller ones; rather, larger communities are less vulnerable to having large portions of their populations killed by (or entirely wiped out by) external enemies compared with smaller ones (i.e., there is safety in numbers). . . .

. . . people living in small-scale societies are not inherently more violent that those living in “civilized” states. Our analyses demonstrate that war deaths scale similarly with population sizes across all levels of human society.

Other scholars have uncovered the same results:

Based on our results, we conclude that trends in proportions of war group size or casualties in relationship to population are, in fact, described by deeper scaling laws driving group social organization subject to contingencies, such as logistical constraints, expedient needs, and technology. . . .

Indeed, while the probability of being involved in conflict as a member of a war group or as a casualty of conflict in large and/or contemporary societies is lower than in small-scale societies, it might not be driven by any better or worse angels of our nature. This probability might merely be an emergent outcome of differential logistical constraints and group populations. This probability may also change rapidly based on group conflict needs, expedience, and contingency. The demographic investment of any society in its own conflict issues or the lethality of any conflict then is not a matter of proportions but of scale. (Oka et al.)

Prehistoric Warfare?

Here is Pinker’s List indicating that extreme violence was more prevalent the further back we go:

Against Pinker’s claims of evidence for prevalent warfare at those twenty-one prehistoric archaeological sites, R. Brian Ferguson assures us that the evidence is simply not there.

Pinker’s (2011, p. 49) List compiles data from Keeley and Bowles to include 21 cases. One case has no killings, and it will be shown that six more of the 21 cases can be tossed out. The others, valid cases of multiple violent deaths, will be shown to be a very selective compilation of high-killing situations, in no way representative of “typical” war casualties of prehistoric people in general. (Ferguson, p. 116)

Ferguson presents readers with a detailed analysis of each of Pinker’s references documenting prehistoric warfare and sums up as follows (and I reformat his paragraph):

So let us look back over Pinker’s list. Of the original 21,

- Gobero, Niger is out because it has no war deaths.

- Three cases, the burial ground across the Nile from Site 117, Sarai Nahar Rai, India, and Calumnata Algeria are all eliminated because they only have one instance of violent death.

- One site each was dropped because of duplication in Brittany, southern Scandinavia, and California.

That leaves two-thirds of the original List, 14 examples, which purportedly represent average war mortality among “prehistoric people.”

- Jebel Sahaba, the two cases from the Dnieper gorge, and Indian Knoll are all highly unusual in their very early dates and number of casualties, when compared to other contemporary locations, including 117’s neighbor’s cemetery (see Ferguson, chapter 11).

- Three European sites are from the Mesolithic, which has gained a reputation for violence compared with earlier and later cultures,

- and two of those are from the Ertebolle tradition, which has an established reputation of being especially violent even within the Mesolithic.

- Four cases (compiled from many more individual sites) are from the Pacific coast, British Columbia, and Southern-Central California, all of which have higher levels of violence than any other long-term North American sequence, and which still show great variations by time and place.

- The final three are from Illinois and South Dakota or thereabouts, which, even during the most violent centuries in the entire sequence of prehistoric North America, stand out as the extreme points of warfare killings.

Of the figures used by Pinker Ferguson avers

Is this sample representative of war death rates among prehistoric populations? Hardly. It is a selective compilation of highly unusual cases, grossly distorting war’s antiquity and lethality. The elaborate castle of evolutionary and other theorizing that rises on this sample is built upon sand. Is there an alternative way of assessing the presence of war in prehistory, and of evaluating whether making war is the expectable expression of evolved tendencies to kill? Yes. Is there archaeological evidence indicating war was absent in entire prehistoric regions and for millennia? Yes. The alternative and representative way to assess prehistoric war mortality is demonstrated in chapter 11, which surveys all Europe and the Near East, considering whole archaeological records, not selected violent cases. When that is done, with careful attention to types and vagaries of evidence, an entirely different story unfolds. War does not go forever backwards in time. It had a beginning. We are not hard-wired for war. We learn it. (Ferguson, p. 126)

Or maybe the “learning” of it is related to how our “hard-wired” nature responds to larger and more complex communities?

In chapter 11 Ferguson concludes

But more than that, before war became “normal,” there may have been developed cultural systems to prevent conflict from turning into collective violence. Cross-cultural research tells us that there are factors and forces which promote peace, which are quite distinct from those that encourage war. The comparative record from Europe and the Near East suggests that these could be investigated, if archaeologists recognized the possibility, and chose to investigate them. . . .

Across all of Europe and the Near East, war has been known from 3000 BC, or millennia earlier, present during all of written history. No wonder we think of it as “natural.” But the prevalent notion that war is “just human nature” is empirically unsupportable. The same types of evidence that document the antiquity of war refute the idea of war forever backwards. War sprang out of a warless world. (pp. 228 and 229)

.

Falk, Dean, and Charles Hildebolt. 2017. “Annual War Deaths in Small-Scale versus State Societies Scale with Population Size Rather than Violence.” Current Anthropology 58 (6): 805–13. https://doi.org/10.1086/694568.

Ferguson, R. Brian. 2015. “Pinker’s List: Exaggerating Prehistoric War Mortality.” In War, Peace, and Human Nature: The Convergence of Evolutionary and Cultural Views, edited by Douglas P. Fry, 112–31. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ferguson, R. Brian. 2015. “The Prehistory of War and Peace in Europe and the Near East.” In War, Peace, and Human Nature: The Convergence of Evolutionary and Cultural Views, edited by Douglas P. Fry, 191–240. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oka, Rahul C., Marc Kissel, Mark Golitko, Susan Guise Sheridan, Nam C. Kim, and Agustín Fuentes. 2017. “Population Is the Main Driver of War Group Size and Conflict Casualties.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (52): E11101–10. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1713972114.

Pinker, Steven. 2012. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. Reprint edition. New York: Penguin Books.

Stetka, Bret. 2017. “Steven Pinker: This Is History’s Most Peaceful Time–New Study: ‘Not So Fast.’” Scientific American. November 9, 2017. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/steven-pinker-this-is-historys-most-peaceful-time-new-study-not-so-fast/.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Funny but not one mass shooting occurred involving Neanderthals, just us modern humans.

An awful lot of numbers to crunch in that post. Maybe somebody can show me this bottom line: Am I more likely to be killed by an act of violence now or if I had lived at some random time in the past?

I added the number charts or graphs to demonstrate the validity of the analysis. There is safety in numbers but that does not impinge on whether we are less war-like as a species today than we were in the past. If you walk alone in a dark and dangerous street at night there is a good chance you will become a victim, much more so than if you walk with a handful of others. But that does not mean the street is less dangerous at night, only that the slower or weaker partners are more likely to be caught first allowing you to escape.

If you lived in small tribal group at war with another small tribal group the death toll might be a horrendous 20%. But if you were in a country involved in World War 1 or 2 your the percentage of total population killed would be much less but the total deaths overall would be higher than expected extrapolating from smaller groups. The control chimp studies suggest that we are no less warlike today than our ancestors, and that our warlike customs have magnified since moving into more organized and larger societies.

Statistically, it is about scaling, or linear regression analysis. Pinker confuses individual vulnerability, the chance of any one of us dying, with the overall tendency of our species to wage ever more deadly wars.

I assumed that your purpose in showing the numbers was to demonstrate validity. I would have to do my own analysis of those numbers to know whether they actually demonstrate it, and that would require a commitment of time that I cannot make right now. Thus my question about the bottom line.

As for “whether we are less war-like as a species today than we were in the past,” I did not construe Pinker’s work as an effort to answer that question. I construed it as an argument that, for most of us humans alive today, life is better than it would have been if we had lived at any time in the past. Of course, “better” is a matter of judgment, not of fact. But, in making that judgment, I cannot regard as irrelevant the fact that I am likelier to reach my 80th birthday (not quite six years from now) than I would have been in any previous century.

Of course not everyone in the modern world shares my personal good fortune. This is not the best of all possible worlds, and Pinker has never said it was. I happen to be very pessimistic about our prospects for the near future. But I believe the reason we are headed for a catastrophe is the currently widespread rejection of the very Enlightenment values that were responsible for the progress we actually have made until now.

If you are part of a family group of 10 and 50% of you are killed by raiders, the odds of you surviving are five in ten, but in reality, your chances of surviving are greater if you are part of nation of 200,000,000 and 60% of that nation was wiped out by a nuclear strike. Safety in numbers, as they say. Better chance for you to be one of 80 million survivors than one of five out of ten.

The vulnerability of any particular individual is not a measure of how much more violent war has become.

Hi Neil

I don’t think that’s right – in your nuclear bomb example an individual’s chances of surviving are 40% and are therefore lower than in the small group. Population size does not make a difference if you are already discussing the % of a population harmed.

I think the point made about scaling is more subtle. I think they are suggesting that modern societies have just as many, or more wars. These wars are as common as ever (per society) and bloodier than ever (total casualty figures). They do, however, directly involve a lower % of the population.

Disclaimer: I haven’t read the original paper yet!

I read a bit of the article, and I think the argument the authors are making isn’t that there actually is a higher chance of dying in larger societies, but that “chance of dying” isn’t a useful marker of “violence in a society” because it mechanically scales with population size. Doug Shaver dismisses how we can argue all day about defining “more violent” and “less violent” but it’s actually a pretty relevant question because Pinker isn’t arguing that things are better in our modern societies only because our societies contain more people. His book is called “The better angels of our nature”, not “On the benefits of being in large populations”.

I’m not completely confident I understand the argument the authors are making (and I agree that Neil made a mistake with his numbers here but in other comments he seems to be making the same argument as the one I understood), but I think they’re claiming they found a basic scaling law between population size and the number of dead due to violence, and that they find a similar relationship in chimpanzee societies. This is certainly a decent reason not to use the simple ratio of population size/number of dead as an indicator of anything but population size, just like we don’t use pure muscle mass to measure the strength of an animal or raw brain size to evaluate how big-brained they are. Having established this, they find that in humans, large societies are more violent than you’d expect from the scaling law calculated from chimpanzee societies.

Well, Pinker does say, if I remember correctly, that modern society is, in some general way (allowing for inevitable exceptions) less violent than earlier societies. And so, if the only question is “Was he correct in saying so?” then yes, it is relevant how we define “less violent.”

I did post a comment that I quickly deleted when I suspected I had got muddled with some of the numbers. Unfortunately I think that comment went out to anyone subbed to the comments anyway.

Further, just for clarification, here is Pinker’s claim, the one in question. It is more than simply “less or more violent”. He is speaking of “rates of violent death” — but the problem is his rates are all “rounded” to per 100,000 even though primitive warfare never saw such raw numbers. Scaling has to be factored in.

re Doug Shaver: “And so, if the only question is “Was he correct in saying so?” then yes, it is relevant how we define “less violent.””

That does seem to be the only question interesting you but it’s not the only one as far as I’m concerned, indeed I find that this paper makes a good argument that this is the least interesting question of all (and I don’t even think Pinker would agree with you that this was the point of his book, but I already said that). Which is why I made my reply in response to Geoff S.’s comment, who was discussing his understanding of the paper, and not you.

OK, Neil, lemme see if I’m understanding you correctly.

I can be a member of population A, comprising 10 people, or a member of population B, comprising 200,000,000 people. A war breaks out in both populations, killing 5 in population A and 120,000,000 in population B, which translates mathematically to 50 percent of A and 60 percent of B. That leaves 5 survivors of population A and 80,000,000 survivors of population B. It follows that my odds of survival are 50 percent if I am a member of A and 40 percent if I am a member of B.

But you say I have a better chance of surviving if I belong to B than if I belong to A.

That does not compute. There is no way a 40 percent chance of survival is better than a 50 percent chance.

You follow with a quotation from Falk and Hildebolt that, I gather, is supposed to support your argument. I don’t see how it does so. I do get what they are saying in terms of Pinker’s claim that modern society is less violent than earlier societies. Very well. It can be argued that “less violent” is not the correct term, or not the best term, for characterizing modern society relative to earlier societies. But in the passage you quote, Falk and Hildbert do not refute Pinker’s claim that most people in modern society are less likely to die as victims of war or other violence than their ancestors were.

We can argue all day about how we should define “more violent” or “less violent,” but there is no sensible way to argue that we should prefer a 60 percent chance of violent death to a 50 percent chance of violent death.

Sorry about the typo on Hildebolt’s name.

We are talking about two different things. Pinker is confusing vulnerability of any particular individual with propensity to wage either equally or increasingly violent war. My question was not if 60% is better/worse than 50% in any absolute sense — recall the scenario of walking down a dangerous street at night. Your chances of survival are increased (by 50%, say) if you go with someone (there is a chance they’ll be the victim instead of you) but that doesn’t mean the street is any less violent or dangerous because you are with someone else who, hopefully for you, is a slower runner than you.

One person walks down the street and is murdered: 100% death rate.

Two people walk down the street and one is murdered while the other gets away: 50% death rate.

The street has not suddenly become 50% less violent, though.

It’s a scaling thing. Yes, there’s more chance of you surviving if you are part of a larger group rather than a smaller one. But the stats show that the actual numbers of deaths, when the scaling factor is entered, is much higher than one would expect even though the percentages killed are less. A death rate of 5% tells us very little unless we know the sizes of populations it is being applied to. Pinker dumbs everything “down” to a death rate of per 100,000 even though in primitive warfare the numbers were far, far less than 100,000. Recall the chimp control study.

For the mathematical detail of the scaling effect Falk cites

Armitage, Peter. 1955. Tests for linear trends in proportions and frequencies. Biometrics 11(3):375–386 — https://www.jstor.org/stable/3001775

and

Cochran, William G. 1954. Some methods for strengthening the common x2 tests. Biometrics 10(4):417–451. — https://www.jstor.org/stable/3001616

“Yes, there’s more chance of you surviving if you are part of a larger group rather than a smaller one.”

At a given time and place, sure, but that is not the comparison being made. I don’t recall that Pinker ever claimed that we are better off now than before because there are more of us. As I understood him, he is claiming that we are better off at this time in our history because we are, at this time in history, less likely to die as victims of war or other violence.

Of course that raises the question: Why are we less likely to die from violence now? One possible explanation (A): Because there are more off us, and there is safety in numbers. Another possible explanation (B): A smaller percentage of the total population are inclined to use violence as a means of achieving their goals, whatever their goals are. One other possible explanation (C): Both (A) and (B).

I believe Pinker was arguing for (B), and I find his argument persuasive. I think (A) is also credible, and so I would pick (C).

Now, the benefits of (B) could have been offset by the increasing lethality of modern technology. Obviously, one person or group of people can kill more people at one time than they ever could during earlier times. Notwithstanding that capability, though, the bad guys are not taking out as large a fraction of their fellow humans as they used to. Safety in numbers could be part of the reason. I’m not persuaded that it’s the only reason.

The argument of Pinker being addressed:

I have a subscription to JSTOR through the University of Phoenix, but it still won’t let me access either of those two articles.

The two articles in Biometrics.

That’s odd. I thought they were open access. Anyway, I have added them to Google Drive for a short while now and you and anyone else can access them through the following links. Let me know when you have done that and I’ll remove them just to be on the safe(r) side…

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1JUZXUh6xiHm3mbb-Q08AmOOVEM4eGwJz/view?usp=sharing

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Jof0CM9lPhHBz6TrQYBMEN4ktFAX4_R8/view?usp=sharing

I’ve downloaded both. Thank you very much.

Here is the opening paragraph of Falk and Hildebolt in full. It zeroes in more precisely on the issue they take up with Pinker’s argument:

I have had a couple of statistics classes beyond the introductory level, but I cannot entirely follow the articles by Armitage and Cochran. I cannot tell just by reading them whether they discredit anything Pinker says. I do assume that Falk and Hildebolt are correctly interpreting their work. What is not yet clear to me is whether their work is relevant to Pinker’s overall thesis. Maybe it is; I just can’t tell from reading either Stetka’s or Falk and Hildebolt’s criticisms of Pinker.

Stetka says, “Still, there are many ways to look at the data—and quantifying the definition of a violent society.” Exactly, and until we all agree on one quantified definition of “violent society,” we are literally not talking about the same thing when we argue about relative degrees of violence in various societies. It’s kind of like the abortion debate. Is abortion murder? If the adversaries just don’t mean the same thing when they use the word “murder,” then they are not arguing about the same thing.

So, is the debate over Pinker’s thesis just so much semantic quibbling? No, not any more than the abortion debate is just a semantic quibble. Words are defined by usage, and we have our tribal reasons for preferring some usages over others. Pinker can present his own defense, if he cares to, for defining “less violent” the way he does. I don’t believe that the overall thesis of The Better Angels of our Nature and its followup, Enlightenment Now, depends on whether we accept it. In other words, I would argue, humanity as a whole has made progress—i.e. we are better off than we used to be—even if we stipulate that we are just as violent as we ever were.

“Is abortion murder” isn’t a silly disagreement predicated on not realizing the two sides use “murder” differently. It’s a disagreement about the use of the word, and the reason there’s a disagreement about the use of the word is because there’s also a substantive disagreement on the moral status of abortion.

In this case we don’t have people talking past each other because they haven’t realized they define “violent society” differently. We have authors of a paper making a very specific argument for why “violent society” should be defined their way and not in the way Pinker does. And this disagreement on how one measures the violence of a society isn’t a pure question of semantics, it relates to substantive issues of how violence functions in societies and how we measure how “good” things are in a society (the latter of which is the core of Pinker’s book to begin with – he argues that things are getting better, which means making an argument for how one should measure how good things are).