Forget any notion of an anti-Roman “nationalism” yearning to be free from Rome. Forget messianic hopes and a desire to be ruled by God alone. Steve Mason proposes in A History of the Jewish War, A.D. 66-74 causes much more common to wars more generally:

Forget any notion of an anti-Roman “nationalism” yearning to be free from Rome. Forget messianic hopes and a desire to be ruled by God alone. Steve Mason proposes in A History of the Jewish War, A.D. 66-74 causes much more common to wars more generally:

The Judaean-Roman conflict broke out … not from anti-Roman ideas or dreams among the uniquely favoured Judaean population, but from the sort of thing that more commonly drives nations to arms: injury, threats of more injury, perceived helplessness, the closure of avenues of redress, and ultimately the concern for survival.

(Mason, 584)

Further, there was no massive Judean wide uprising against Rome. Most Judeans either quickly demonstrated their loyalty to Rome or fled for their lives as Nero’s general Vespasian approached. Prior to the siege of Jerusalem, Vespasian’s army “faced little or nothing in the way of combat” (412). [Some readers will immediately be wondering about Joseph Atwill’s account and in particular the “battle of Gadara” will come to mind. At the end of this post I add Steve Mason’s description of that massacre and its context in the “wider war”.]

I’ll attempt a very general overview of what Mason proposes were the steps that led to the war. Doing so means I necessarily gloss over the detailed reasons for each point he makes and for his setting aside the conventional view that Judean resentment against Rome was on the boil until it reached a point where open rebellion was inevitable. So take the following as an invitation to read the book or follow up with further discussion wherever appropriate.

The theme to look out for running through each of the following stages is the tense relationship between Judeans and their neighbours.

Before Rome

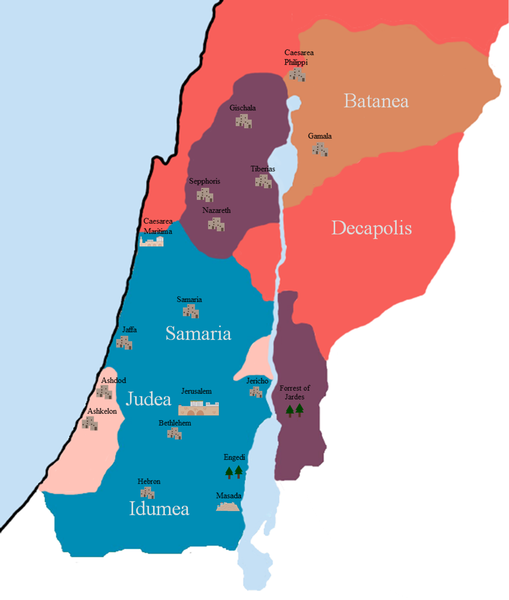

Before the Roman period Judea was a regional hegemon. This had been the work of the Hasmonean dynasty that cowered neighbours — Samaria, the Mount Gerizim temple, cities of the Decapolis — into submission by conforming to Jewish ways or destroyed them.

Rome Enters

The Roman Pompey was thus greeted as a liberator from Judean domination. Pompey reduced Judea to little more than its pre-Hasmonean extent.

Not long afterwards, however, Herod was made a client king of Rome and Judea once again became the regional hegemon. (Mason argues that Judea was not a Roman province at this time but was an ethnic region of southern Syria. Syria itself was a Roman province. Judea did not become a Roman province until after the Jewish War.)

So Herod’s Kingdom of Judea was permitted to extend even beyond what it had been during Hasmonean times. Unlike the Hasmoneans, though, Herod did not attempt to Judaize his neighbours. Samarians and Idumeans were permitted their own institutions, cultures and cults.

Herod Dies

Herod died and the Roman emperor Augustus respected his will that his kingdom be divided among his three sons:

Archelaus turned out to be the black sheep of the family and soon lost the support of key groups among his subjects. Pleas to Augustus for his removal succeeded.

(IN)SIgnificance of Judas the Galilean

Josephus informs us that after the removal of Archelaus there arose (6 C.E.) “a certain Galilean fellow by the name of Judas” who attempted to instigate a rebellion and calling for no ruler but God alone! Mason challenges the common view that this Judas marked the beginning of Judea’s “nationalist” movement for freedom from Rome:

Solomon Zeitlin put the standard view succinctly: “The Sicarii were the followers of the Fourth Philosophy which was founded by Judas of Galilee in the year 6 CE.”170 To untangle the knot of assumptions behind this, we must reconsider the evidence. Fortunately, there is little. (Mason, 245)

Mason focuses on the timing of the protests. That a protest movement began soon after the removal of Archelaus and the incorporation of Judea into the province of Syria (an event that would have entailed a census on Judea) is not likely coincidence. It is not likely that anti-Roman feeling suddenly flared up at this point after having been in effect for seventy years by this time. The other regions where there was no change, those that continued under Antipas and Philip, saw no uprising.

No, according to Mason, any form of revolt at this time is best understood as a change in the status of the Judeans as they were incorporated into the province of Syria and their centre of administration moved to Caesarea. That involved a major shift in relations with neighbouring ethnic groups as we see in the next section.

turning point — Caesarea and a samarian force dominate

With the removal of Archelaus the centre of administration shifted from Jerusalem to Caesarea.

Herod’s army had been a “multi-ethnic” organization but with the removal of Archelaus the armed forces that were the means of maintaining order lost their large Jewish component and became predominantly Samarian.

In other words, with Caesarea now the administrative centre, a Samarian force was set over the Judean population. Continue reading “What Caused the Jewish War of 66-74 CE?”