The influences of Mesopotamian creation stories in Genesis are clear. But how those stories came to be re-written for the Bible is less clear. Russell E. Gmirkin sets out two possibilities in Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch:

The traditional Documentary Hypothesis view:

Around 1400 BCE the well-known Babylonian Epic of Creation, Enûm Elish, the Epic of Gilgamesh and other stories found their way through Syria and into the Levant where the Canaanites preserved them as oral traditions for centuries until the Israelites learned of them. Then around the tenth or ninth centuries these Israelites incorporated some of those myths into an early version of Genesis (known as J in the Documentary Hypothesis).

About four centuries later, around the fifth century, the authors of that layer of the Bible known as P took quite independently orally preserved overlapping Mesopotamian legends and used them to add additional details from those myths that had been preserved by the Jews orally throughout to the J stories.

Now one remarkable aspect of this scenario (accounting for the Mesopotamian legends underlying Genesis 1-11) that has been pointed out by Russell Gmirkin is that though they had been preserved orally for centuries by the Canaanites, in Genesis they are completely free from any evidence of Canaanite accretions. This should be a worry, says Gmirkin, because Canaanite influences are found throughout the rest of the Bible.

Gmirkin suggests that this traditional model of how the Babylonian legends came to be adapted in the Genesis narrative is strained, so he proposes an alternative.

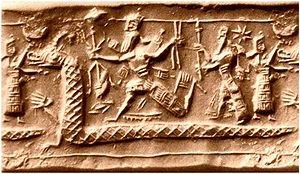

The author/s of Genesis 1-11 borrowed directly from the early third century (278 BCE) Babyloniaca of the Babylonian priest Berossus. The sources for this work show that Berossus himself drew upon the Babylonian epics of Creation and Gilgamesh, and Gmirkin argues that some of his additions and interpretations found their way into Genesis. Moreover, the Epic of Creation that resonates in Genesis, the Enûm Elish, was quite unlike other Babylonian creation myths:

- the standard Babylonian myth of creation (e.g. Atrahasis Epic, Enki and Ninmeh) began with earth, not with waters;

- Enûm Elish was specifically associated with the cult of Marduk, localized in Babylon — its purpose was to explain why the Babylonian patron god, Marduk, had been promoted over the other gods.

Note also:

- during the late Babylonian period and Seleucid times, the Enûm Elish likely increased in significance, but was still only recited in Babylon’s New Year Festival;

- Berossus was himself a priest of Bel-Marduk in Babylon at this period. For Berossus, the Enûm Elish would have been the definitive creation epic.

The Enûm Elish was very likely unknown beyond the region of Babylonia until Berossus himself drew attention to its narrative for his wider Greek audience. Gmirkin believes the simplest explanation for the Enûm Elish’s traces in Genesis is that they were relayed through Berossus’s Babyloniaca.

Here is a table comparing the details of the Genesis Creation with those found in the Babylonian Creation Epic and in Berossus’s third-century work: Continue reading “The Genesis Creation Story and its Third Century Hellenistic Source?”