A Long-standing Tool

A Long-standing Tool

While searching for other things, I stumbled upon this paragraph in a Wikipedia entry.

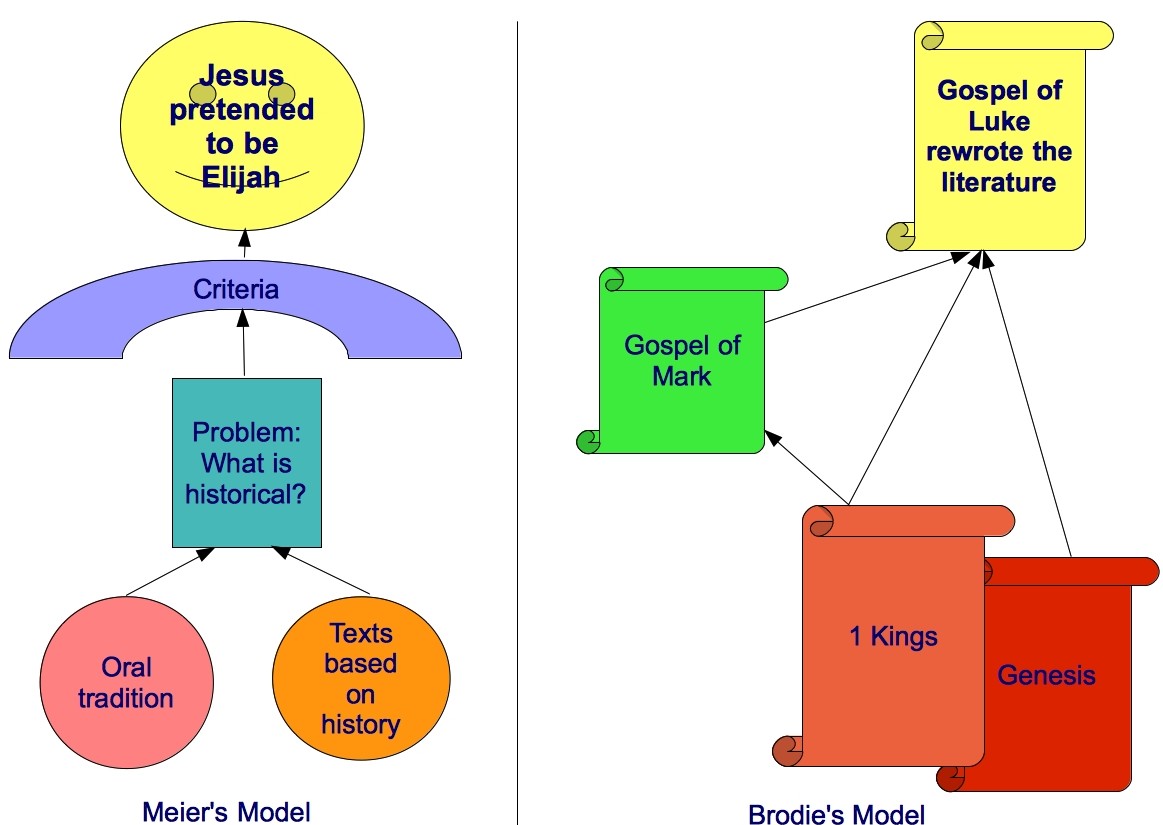

The criterion of embarrassment is a long-standing tool of New Testament research. The phrase was used by John P. Meier in his book A Marginal Jew; he attributed it to Edward Schillebeeckx, who does not appear to have actually used the term. The earliest usage of the approach was possibly by Paul Wilhelm Schmiedel in the Encyclopaedia Biblica (1899).* (Wikipedia: Criterion of embarrassment, emphasis mine)

* Stanley E. Porter, Criteria for Authenticity in Historical-Jesus Research (Continuum, 2004) pages 106-7.

Having read Schillebeeckx, I was taken aback. Didn’t he mention the term “embarrassment” in Jesus: An Experiment in Christology? In a post from 2013, we quoted him:

Each of these gospels has its own theological viewpoint, revealed by structural analysis no less than by disentangling of redaction and tradition. Via their respective eschatological, Christological or ecclesiastical perceptions they give away their theological standpoint through the selection they make of stories reporting the sayings and acts of Jesus, as also in the way they order and present the material. Consequently, whenever they hand on material not markedly in accord with their own theological view of things, we may take this to be a sign of deference in the face of some revered tradition. (Schillebeeckx 1981, p. 91, emphasis mine)

Hey, Porter!

Perhaps I had a false memory. It wouldn’t be the first time. Could he have discussed the mechanics of the criterion without ever using the word itself? I turned to Porter, who in a footnote wrote the following: Continue reading “The Criterion of Embarrassment: Origins and Emendations”