Time once more to pull out my copy of Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (Afshon Ostovar). I’ve referred to it a few times now:

Time once more to pull out my copy of Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (Afshon Ostovar). I’ve referred to it a few times now:

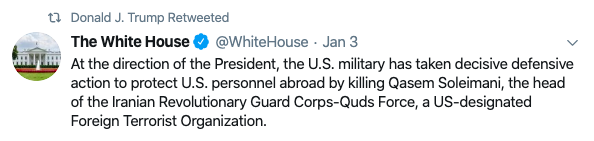

It’s first reference to Qassem Soleimani is in its Introduction:

Also significant were placards in honor of Qassem Soleimani—the architect of the IRGC’s [= Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corp] foreign operations. Soleimani earned the reputation as a savvy strategist during the US occupation of post-Saddam Iraq, during which he organized an effective counterweight to American influence through the development of a Shiite militant clientage. This work made Soleimani—often referred to with the honorific “Hajj”—a revered figure within IRGC ranks. He was considered the one most directly responding to Iran’s grievances by confronting its enemies on the battlefield. The supreme leader even referred to Soleimani as a “living martyr” for his efforts—placing him iwithin the pantheon of Shiite-Iranian heroes. As one sign proclaimed, “We are all Hajj Qassem!” (p. 3. Highlighting is mine in all quotations)

Also significant were placards in honor of Qassem Soleimani—the architect of the IRGC’s [= Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corp] foreign operations. Soleimani earned the reputation as a savvy strategist during the US occupation of post-Saddam Iraq, during which he organized an effective counterweight to American influence through the development of a Shiite militant clientage. This work made Soleimani—often referred to with the honorific “Hajj”—a revered figure within IRGC ranks. He was considered the one most directly responding to Iran’s grievances by confronting its enemies on the battlefield. The supreme leader even referred to Soleimani as a “living martyr” for his efforts—placing him iwithin the pantheon of Shiite-Iranian heroes. As one sign proclaimed, “We are all Hajj Qassem!” (p. 3. Highlighting is mine in all quotations)

and

Ostovar explains Quds: Quds Force is a … selective organization. As its name implies, the Quds Force—Quds means Jerusalem in Persian and Arabic—was originally conceived as a division that would lead the IRGC’s efforts against Israel. However, its mandate has grown over the years to encompass all of the IRGC’s foreign covert and military operations. Its members are some of the best trained in the IRGC, having received advanced instruction in areas such as explosives, espionage, tradecraft, and foreign languages. There is no accurate reporting of the Quds Force’s size, but estimates generally peg its membership between five thousand and twenty thousand individuals. The primary function of Quds is to develop and assist allied armed groups outside of Iran. It helps train, equip, and fund a variety of organizations across the greater Middle East. This work has brought it into close partnerships with groups such as Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza, the National Defense Forces in Syria, the Badr Organization in Iraq, and Ansar Allah (also known as the Houthis) in Yemen.

In Iraq . . . Quds chief Qassem Soleimani was able to subvert the influence of the United States by building up a network of pro-Iranian, anti-American Shiite militant groups. These groups fought American and allied troops, and secured powerful positions in Iraq after US combat forces withdrew in 2011. They remain one of the most powerful constituencies in Iraq and have made Iran a dominant player in that country. (p. 6)

After 9/11 Iran was prepared to cooperate with the United States in its war against the Taliban and Al Qaeda in Afghanistan, supplying the U.S. with the detailed location of Taliban and Al Qaeda targets and advising on the best plans for destroying them. Soleimani was said to have been “very pleased” with the cooperation, but then came the Bush led betrayal of Iran and Soleimani’s assistance. The details are posted at

Iran, Iran, if only we had been friends

(2018-09-24)

(I seem to recall another recent betrayal — this time of an Iranian ally that also had a strong record of helping the U.S. defeat ISIS — by Trump.)

Moving on to the period of Iraq’s Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki. . . .

Unable to achieve his goals [to crush the Iraqi Shiite militia opposing the Sunni dominated government] militarily, Al-Maliki was forced to send a team to negotiate a ceasefire with the Basra groups in Qom, Iran. The man behind the deal, as first reported by McClatchy’s Leila Fadel, was Quds Force chief Qassem Soleimani. Part of the agreement included an offer by Maliki to absorb Badr Organization militants into Iraq’s security forces—a move that further entwined pro-Iranian and IRGC-linked elements with the Iraqi government.

Soleimani’s role in the Basra ceasefire highlighted Iran’s growing influence in Iraq. It also signaled Soleimani’s emergence as a powerbroker. Recognizing his own rising stock, in May 2008 Soleimani sent a letter to his “counterpart” in Iraq, US General David Petraeus, suggesting that the two meet to discuss Iraqi security. Petraeus dismissed the letter, but Soleimani’s message was clear: Iran had amassed considerable power in Iraq and would have to be engaged for stability in that country to be achieved. That event was the high watermark of Iranian influence in Iraq during the first half-decade of the US occupation. (p. 174)

Responding to the Collapse of the Soviet Union and Emergence of the Arab Spring

The potential for a fundamental political reorientation in the Middle East was at its most acute since the fall of the Soviet Union. The region was going to change. How and to what end was the question. The Islamic Republic saw peril and opportunity. As Quds Force chief Qassem Soleimani explained in May 2011, the unfoldment of the Arab Spring was as critical to the future of the revolution as the war against Saddam. “Today, Iran’s defeat or victory will not be determined in Mehran or Khorramshahr, but rather, our borders have spread. We must witness victories in Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria.” In order to safeguard its interests and counter its enemies, Tehran had to look beyond its borders. If it failed to help determine the future course of the Middle East, Iran’s enemies would be the beneficiaries.

Soleimani was not speaking rhetorically. He was expressing an evolving view in the IRGC that it not only had the responsibility but the ability to advance Iran’s agenda outside its borders. The IRGC had learned with the fall of Saddam that it could successfully exploit power vacuums for strategic gains. Syria’s civil war and the war against ISIS in Iraq were new entryways for the organization. Under the direction of Soleimani, the IRGC led Iran’s campaigns of assistance in both countries. These were in large part strategic efforts designed to protect Iran’s allies and equities from hostile forces. But their resilience was rooted in religion. The IRGC framed its involvement in both countries in religious terms. In Syria, the IRGC was defending the shrine of Sayyida Zaynab—a mosque built near Damascus that Shiites believe houses the remains of Zaynab bint Ali, a sister of the Imam Husayn and revered hero in Shiism—and in Iraq, it was safeguarding the holy shrines of the imams and the Shia population. As the IRGC saw it, these conflicts were part of a larger war waged by Sunni Arab states and the West against Iran and its allies. It was a war intrinsically against Shiism and the family of the Prophet. To defeat the jihadist scourge and its Sunni Arab benefactors, the IRGC mobilized pro-Iranian, pro-Shiite supporters in Syria and Iraq. These relationships helped Iran advance its agenda and expand its influence. They also intensified sectarian hatreds. (p. 205)

The Critical Importance of Syria

Continue reading “Who was Qassem Soleimani?”

Like this:

Like Loading...