The following is my own adaption from Philip Davies’ In Search for Ancient Israel, and is not to be taken as  representing Philip Davies’ views on the question of the historical Jesus. In 1992 Davies argued that the scholarly search for “ancient Israel” was at the time always based on the unquestioned assumption that there was an “ancient Israel” to be found. It was always taken for granted. The research was only about deciding how much of the biblical literature was historical, and what this ancient Israel must have looked like. Since I began studying the scholarly works about Christian origins and the historical Jesus, it has struck me that the same flawed assumptions and circular reasoning lies at the heart of these studies, too.

representing Philip Davies’ views on the question of the historical Jesus. In 1992 Davies argued that the scholarly search for “ancient Israel” was at the time always based on the unquestioned assumption that there was an “ancient Israel” to be found. It was always taken for granted. The research was only about deciding how much of the biblical literature was historical, and what this ancient Israel must have looked like. Since I began studying the scholarly works about Christian origins and the historical Jesus, it has struck me that the same flawed assumptions and circular reasoning lies at the heart of these studies, too.

Someone responded that the situations are completely different because the Gospels are written within the same time frame as the events they purport to describe. But it can be shown that the logic of this rejoinder is also circular. (Nonetheless, Davies’ argument about the study of “ancient Israel” is based in part on the ability to set the composition of the literature to Persian and Hellenistic times. Since this is a literature about an entire Kingdom and claims to be set within the time of that kingdom, this is necessary. The Gospels are not about a nation, but about a single person who was said by some sources to have been unrecognized in his time, and do not specifically claim any particular date for composition. They have been dated everywhere from the 30’s or 40’s to the 130’s or 140’s. But as with the Old Testament literature, most of the earlier dates are based on an assumption of the historicity of parts of the narrative itself.)

Nor do I see this as a negative or anti-Christian question. My atheism has not led me to question the Bible or God or religion. It was my questioning of these that led, rather, to my atheism. What I find fascinating is the study of Christian origins. My ongoing interest is an intellectual one and has nothing to do with finding supports for faith or reasons to reject faith. If that study uncovers a historical person at the heart of the process, then so be it. But so far I have seen no methodological or evidential reasons for positing such a person as a satisfactory explanation of the nature of the evidence.

In what follows, I have replaced Davies’ references to “Israel” with references to “Jesus” or “Christian origins”. The page references are to In Search of Ancient Israel. The following are not Davies’ views in this book. They are entirely my own adaptation of a few aspects of Davies’ argument to historical Jesus studies.

Opening up the question, not closing it

“Now let me be clear: I am not as yet saying that the literary [Jesus] must be assumed a priori to be unhistorical. What I am saying is that it is literary and that it might be historical.” (p.24)

Seems absurd

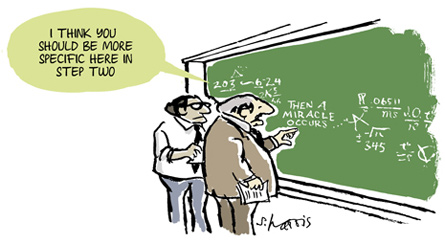

“The very raising of the question might seem absurd, deliberately provocative, programmatically negativistic. Virtually a whole discipline, after all, is predicated on the existence of an [historical Jesus]. But it is not absurd at all to ask the question. . . . It only seems absurd because scholars have never opened the question, so that it seems entirely off the agenda. It is the kind of question that threatens with a new paradigm, like the absurd idea that the earth orbited round the sun or that slavery was not a divinely-ordained institution. The student of the Bible gets the impression that [the historical Jesus] really did exist because she or he reads about [him] all the time. One might doubt that the Bible is not history, but one can surely not doubt a battalion of professors!” (p.25)

Compromise has ruined everything

“We have not set about arguing that the literary [Jesus] is an historical entity . . . . we have from the outset assumed it. Literary periodization becomes historical time, literary figures are transmuted into historical figures. There are some exceptions, of course: [the slaughtered babes of Bethlehem, Gabriel] and maybe even [Judas Iscariot and Joseph of Arimathea] (for the daring) are eliminated. But taking these figures out makes matters worse rather than better: the result is something that is neither historical nor biblical, but scholarly rationalisation of the literary and the historical. Literary criticism of the Bible became, for generations of students, an historical enterprise.” (p.24)

Never a hypothesis, never a reason to doubt

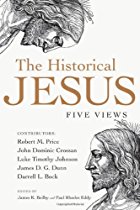

Robert M. Price lays out 5 ground rules for historical enquiry in his opening chapter, Jesus at the Vanishing Point, in

Robert M. Price lays out 5 ground rules for historical enquiry in his opening chapter, Jesus at the Vanishing Point, in