Then God said, “Let us make humankind in our image [LXX εικόνα], according to our likeness [LXX όμοίωσιν]; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.” So God created humankind in his image [LXX εικόνα], in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. (Gen 1:26-27)

RG focuses on two interesting details here.

1. Whereas plants, sea creatures, land animals are made “after their own kind”, mankind is made in the likeness of the gods — made in the genus of God.

In Gen 1:26 the Septuagint renders … “in our image according to our likeness” with …. “according to our image and according to [our] likeness”,. . . using the double κατά (“according to”) . . . . The κατά phrases . . . echo the phrase κατά γένος (“according to [its] kind”) of the preceding verses, suggesting more strongly than in the Hebrew that humankind belongs to the γένος [=race, genus] of God, or, at least, highlighting the contrast with the animals more strongly than in the Hebrew. (Loader, 27f)

2. In creating mankind we read God for the first time saying “Let us…”, that is, “Let us make man in our image.”

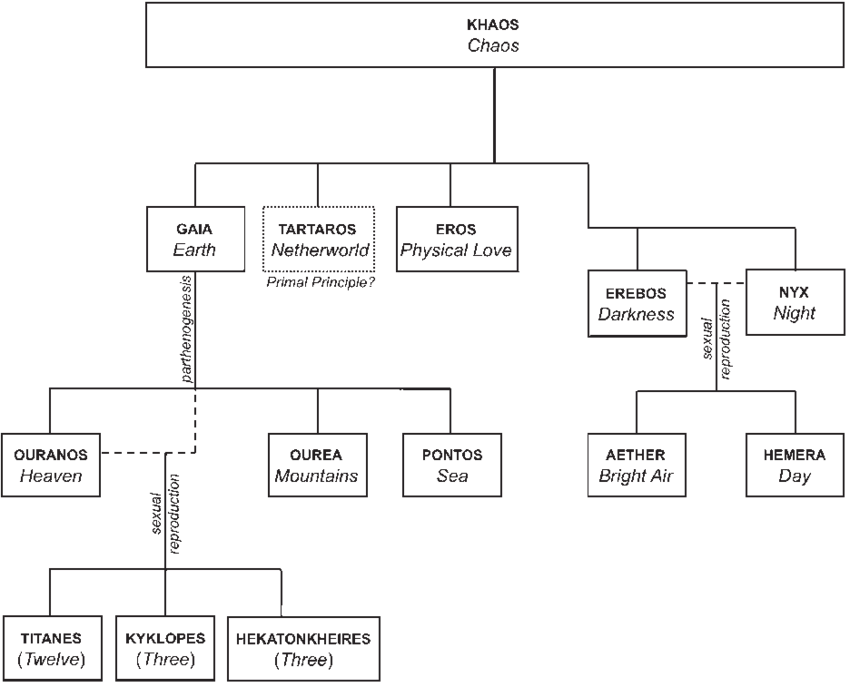

The language employed here, which points to some form of gathering of the gods, who state their intention to create humans in their image, implicitly recognizes older, polytheistic traditions. The announcement of their collective decision to make humankind suggests the divine council as narrative context (Westermann 1984: 144). Creation in the divine image is distantly reminiscent of Mesopotamian regnal imagery, where the king was created in a god’s image . . . , but here it was all of humanity that was created in the image of the gods. It is likely that both male and female gods were here envisioned, since humans were created “in the image of the Elohim… male and female” (Gen 1:27). (Gmirkin, 136)

“Let US . . .“

Various attempts have been made to explain God saying: “Let us….”. Westermann (cited by RG) believes the most economical explanation is that “Let us” implies a council of gods involved in the decision to create humans. Compelled to find out what was behind that interpretation I turned to Westermann who cited Schmidt and Schmidt, it turned out, said everything Westermann said except in German. (The price one sometimes pays just to be sure!) — Here is a synopsis of Schmidt’s (Westermann’s) argument:

Is it the Trinity speaking?

An early church view was that God was speaking as the Trinity. There is nothing else in Genesis to suggest the Trinity so we can put that view aside.

RG in another forum discounted the “plural of majesty” explanation:

I did a pretty thorough independent research on that whole “plural of majesty” thing. This theory was first put forward, as near as I can discover, after the time of Elizabeth I, who famously started the English custom of monarchs referring to themselves as “we”. I can find no evidence that this was earlier put forward as an explanation of Elohim, and no evidence of any ancient god in the Mediterranean or Ancient Near Eastern world in any language referring to themselves in the plural. I haven’t found other academics who have undertaken a similar study on the history of scholarship on this topic, so don’t cite me as a source, since there’s always the chance that I missed something. . . . .

Esther 8.8 allegedly has Ahasuareus refer to himself in the third person, but I don’t read it that way. In any case that is different from referring to himself in the plural (which I can’t find anywhere in Esther or elsewhere of a king or god in the biblical text). . . .

Is it a plural of majesty?

Another is that we have a “plural of majesty” … as in the monarch saying “we” where lesser mortals would simply say “I”. Exegetes who have worked on the view that Genesis was written very early have discounted that possibility because a clear instance of a “plural of majesty” only appears elsewhere for the first time in the mouth of the Persian king in the Book of Esther. (RG, though, does argue for a post-Persian era composition of Genesis.)

Is it a council of gods?

Note that God is found speaking of “us” in other books of the Old Testament whenever he is in a council with other divine beings. [See the insert below for references.] But again, many scholars have been reluctant to accept the view that God is addressing a council of gods in Genesis because they are convinced that the (“priestly”) author would never have thought to imagine God as a “first among equals”.

Is God talking to himself?

Another view: are we reading here God turning over an idea in his mind, speaking to himself? The problem with that view is that there is nothing in the declaration to suggest a pondering: the words are a proclamation, an announcement, of what “they” are about to do.

After weighing up the above options, Schmidt concludes that the sentence here is a relic from a polytheistic era. Both Schmidt and Westermann conclude that the saying originated in the context of a heavenly court of divine beings but continued as a form of speech even after the idea of a heavenly court was no longer part of their belief system. No doubt many later readers and copyists did treat it as a form of speech and ignored its original and literal meaning. But that leaves open the question of why the first author chose to use the expression. For RG, we have here one more instance of a borrowing from Plato:

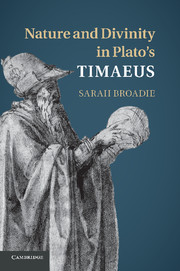

In light of Plato’s Timaeus, the appearance of a multiplicity of gods becomes entirely comprehensible. (Gmirkin, 136)

In Timaeus the Demiurge or Craftsman God first created the universe and then in a subsequent stage delegated the creation of humanity to the other gods he had also created. That Creator God addressed these lesser deities to explain why he wanted them to be the ones to create humankind:

Once all the gods had been created — both those that traverse the heavens for all to see and those that make themselves visible when they choose — the creator of this universe of ours addressed them as follows: ‘Gods, divine works of which I am the craftsman and father, anything created by me is imperishable unless I will it. Any bond can be unbound, but to want to destroy a structure of beauty and goodness is a mark of evil. Hence, although as created beings you are not altogether immortal and indestructible, still you shall not perish nor shall death ever be your lot, since you have been granted the protection of my will, as a stronger and mightier bond than those with which you were bound at your creation. ‘Now mark my words and apprehend what I disclose to you. Three kinds of mortal creature remain yet uncreated, and while they remain so the universe will be incomplete, for it will not contain within itself all kinds of living creatures, as it must if it is to be perfect and complete. If I were to be directly responsible for their creation and their life, they would have the rank of gods. To ensure that they are mortal, and that this universe is truly whole, it is you who must, in fulfilment of your natures, imitate the power that I used in creating you and turn, as craftsmen, to the creation of living creatures. . . . .

After this, he handed over to the younger gods the task of forming their mortal bodies. When they had also created any further attributes a human soul might require, and whatever went along with such attributes, he left it up to them to govern and steer every mortal creature as best they could, so that each one would be as noble and good as it might be, apart from any self-caused evils. (41a – 42e; Waterfield translation)

Sarna in his commentary on Genesis supports the interpretation that “Let us” is a pointer to a heavenly court:

Let us make The extraordinary use of the first person plural evokes the image of a heavenly court in which God is surrounded by His angelic host.20 Such a celestial scene is depicted in several biblical passages. This is the Israelite version of the polytheistic assemblies of the pantheon — monotheized and depaganized. It is noteworthy that this plural form of divine address is employed in Genesis on two other occasions, both involving the fate of humanity: in 3:22, in connection with the expulsion from Eden; and 11:17, in reference to the dispersal of the human race after the building of the Tower of Babel. (Sarna, 12)

The image of God

What does the expression — “image of God, after our likeness” — mean? The fact that these words are not explained in Genesis indicates that it was well enough understood not to need further explanation at the time it was written (Schmidt, 136). So we must look for parallel usages. If we turn to Mesopotamian creation stories, however, we search in vain:

Can a precursor of the tradition be found in the ancient Orient? Although the similarity between God and man is repeatedly stated there in that man is said to be created from clay and the blood of the gods or even in the divine image, the expression “image of God” hardly has its home in the (Babylonian) creation myths. (Schmidt, 136f – translation. Cited by Clines who is cited by Gmirkin, 136)

What happens when we look in another direction? Continue reading “When God Created Humans, then Retired: Genesis 1 as Science — [Biblical Creation Accounts/Plato’s Timaeus – 5c]”