Human rights — they are so Western! But how can anyone, any culture, frown upon them and want them excluded from their frame of reference? Think China.

Human rights — they are so Western! But how can anyone, any culture, frown upon them and want them excluded from their frame of reference? Think China.

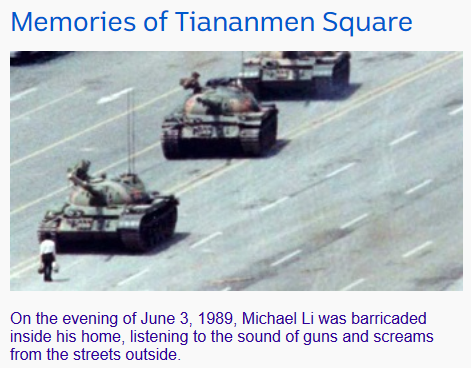

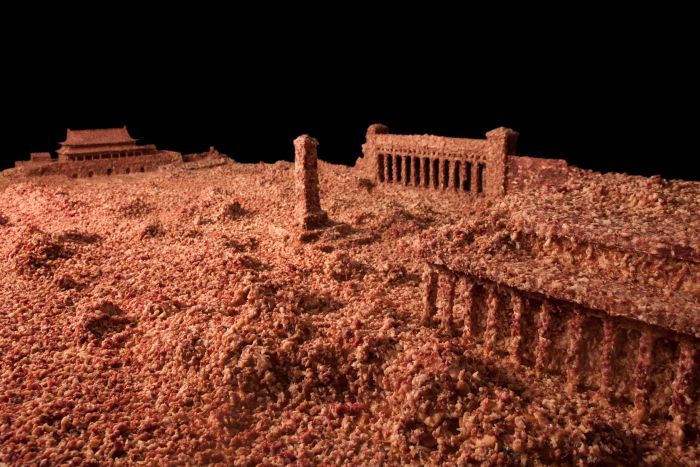

Around twenty years ago I visited Tiananmen Square. Soldiers, every few metres it seemed, still guarded the space. One could not just freely wander anywhere there as if it were what we imagine a public space to be. My sobered looks were noticed by my Chinese companions and they clearly looked worried at my change of mood. They (my companions) were good people, they said. After those “very bad” people did something in the square years before, soldiers or police visited their houses and left when they were assured that they were only good people and not the bad ones causing the trouble. Those were their words: good and bad people. They were horrified that I should seem to display any regrets about that time and they tried to extricate me from that area as quickly as possible. No doubt there are Chinese who feel my horror more than I can but they must remain hidden, even now.

Not long afterwards I took in a Chinese student boarder. She expressed shock when she saw on the TV news film of opposition party figures in Parliament verbally attacking those on the government side. To her she was witnessing anarchy, treason even. At one point she tried to educate me by having me analyze the word “government”: it had “govern” in it, and did not that mean that those in government must “govern”? What right, how on earth …. what a display of utter rabble and rebellion to have people attack the government!

I am currently reading three books. One of them is Kevin Rudd‘s The Avoidable War. He knows a thing or two about China. Here are some passages I have found interesting so far. Confucianism is no longer dead in Communist China:

But Xi Jinping made cultivating nationalism an even stronger priority, leveraging an increasingly sophisticated propaganda apparatus that has seamlessly fused the imagery of the modern CCP with the national mythology of a proud and ancient Chinese civilization.

This has included the rehabilitation of Confucianism, once dismissed by the CCP as reactionary and anticommunist, as part of the restoration of the party’s emphasis on the uniqueness of China’s national political philosophy. According to the official line, a long-standing continuity of benign hierarchical governance (as represented by Confucianism) is what differentiates China from the rest of the world. The shorthand form of Xi’s political narrative is simple: China’s historical greatness, across its dynastic histories, always lay in strong, authoritarian, hierarchical Confucian governments. By corollary, China’s historical greatness was never the product of Western liberal democracy or any Chinese variation of it. By extension, China’s future national greatness can lie only in the continued adaptation of its indigenous political legacy, derived from the hierarchical tradition of the Confucian/communist state. (87f)

It’s about Party legitimacy in the eyes of the people. As long as the Party can oversee rising living standards, a cleaner environment, and a consolidation (even restoration!) of China’s national borders, then the Party is safe. Confucianism: “benign hierarchical governance.”

Human rights?

Like most of his colleagues across the CCP leadership, Xi has long seen US support for universal human rights, democracy, and the rule of law as a fundamental challenge to the party’s interests. Lest there be any doubt on this score, China’s indigenous democracy movement has long been condemned by the party as one of the “five poisons” that threaten the Chinese system, together with Uyghur activists, adherents of Falun Gong, Tibetan activists, and the Taiwanese independence movement—all of which the party contends are backed by the United States.

The party’s historical antagonism toward human rights, electoral democracy, and an independent legal system will, therefore, continue because these concepts strike at the very heart of the perceived legitimacy of the Chinese party-state, both at home and abroad. This explains China’s continuing hostility toward any foreign government that dares challenge the moral fundamentals of the Chinese political system. . . .

That Xi implemented a wide-ranging crackdown against “bourgeois liberalization” in China’s education system during the first six months of his term in 2013 is, therefore, unsurprising. He identified seven sensitive topics that could no longer be the subject of any form of academic discussion or debate. These were “universal values, freedom of speech, civil rights, civil society, the historical errors of the Communist Party, crony capitalism, and judicial independence.” This was followed in 2017 by China’s new foreign NGO law, which placed new security restrictions on the operations of any NGO attracting philanthropic funding from abroad. With the strike of a pen, this law crushed an active civil society that developed over decades, with organizations promoting everything from occupational health and safety to the schooling of migrant workers’ children. Then, more recently, Xi has also moved to ban private schooling and the hiring of foreign teachers as well as the use of international textbooks and curricula. (91f)

One of the other books I am reading now has many references to Plato. I can’t help thinking Plato would have some admiration for Xi Jinping’s policies – except for his nationalist ones that risk war.

Rudd, Kevin. The Avoidable War: The Dangers of a Catastrophic Conflict between the US and Xi Jinping’s China. New York: PublicAffairs, 2022.