I think a wider discussion of Nero is necessary in order to help us understand the context of matters arising in any discussion about Nero’s purported persecution of Christians. Here are a few details that I think are relevant, all from Anthony Barrett’s book, but from chapters either side of the fifth that is the treatment of the persecution we read in the Annals of Tacitus.

I think a wider discussion of Nero is necessary in order to help us understand the context of matters arising in any discussion about Nero’s purported persecution of Christians. Here are a few details that I think are relevant, all from Anthony Barrett’s book, but from chapters either side of the fifth that is the treatment of the persecution we read in the Annals of Tacitus.

This post has three parts:

1. When did the rumours that Nero was to blame for the Great Fire start?

2. Did Nero fear the populace was blaming him for the fire? Who hated Nero the most?

3. Three Nero pretenders.

The Rumours

A central point in the text of Tacitus is that Nero targeted the Christians in order to deflect suspicions that he himself was responsible for starting the fire of Rome in 64 CE.

During Domitian’s reign, some time in the 90s, a poet Statius wrote in praise of another poet, Lucan, who had had a strained relationship with Nero (Nero forced him to commit suicide) by saying that he, Lucan,

. . . will speak of the horrendous flames of the guilty tyrant . . . ranging over the heights of Remus.

Had Lucan accused Nero of starting the fire in one of his poems?

Another literary work from the Flavian era (late first century) is the Octavia, a tragedy about Nero’s first wife. In the play,

Nero invokes a fiery destruction on the city (line 831): “soon let the city’s dwellings collapse in my flames” (flammis . . . meis). The simple addition of the adjective “my” (meis) to the flames (flammis) leaves no doubt about the emperor’s supposed role. (Barrett, p. 122)

Josephus was a contemporary of Nero and in his Jewish War (written about ten years after the fire of Rome) he listed Nero’s sins:

Through excess of prosperity and wealth Nero lost his balance and abused his good Fortune outrageously. He put to death in succession his brother, wife, and mother, turning his savage attention next to his most eminent subjects. The final degree of his madness landed him on the stage of a theatre. But so many writers have recorded these things that I will pass over them and turn to what happened to the Jews in his time. (G. A. Williamson’s translation, p. 134)

No mention of burning much of Rome to ashes.

Then there’s Pliny the Elder. I quote Barrett:

On the other hand, Nero does seem at first glance to be blamed by an older contemporary of the emperor, the Elder Pliny. In his account of the particularly fine lotos trees found on the Palatine, published in AD 77 in The Natural History . . ., Pliny says that the trees lasted until Nero’s fires (ad Neronis principis incendia), in the years when he burned down the city. Pliny adds that the trees would have remained green and youthful had the princeps not speeded up the death of trees as well (ni princeps ille adcelerasset etiam arborum mortem). The “as well” (etiam) presumably implies that Nero killed trees as well as people as a result of the fire. This does seem pretty damning. But all is not as it appears. The words “in the years when he burned down the city” (quibus cremavit urbem annis postea) do not appear in one of Pliny’s manuscripts (MS D) and as far back as 1868 were dismissed from the other manuscripts as a later gloss (a comment added by a scribe). Also, in the final part of the sentence there is a very awkward repetition of the word princeps. There is also the equally awkward unspecific etiam (“also”), which seems to suggest that Nero killed people also, but those unspecified people have not been previously mentioned. Hence it is very possible that the phrase blaming Nero is a later addition to Pliny’s manuscript, supplied by a scribe trying to be helpful and informative, or perhaps just mischievous. Pliny does refer to the “fires of the emperor Nero” (Neronis principis incendia) in the uncontested part of the manuscript, which might be intended to convey the notion of Neronian guilt. But the phrase could be simply a chronological marker. Clearly it would be dangerous to use Pliny as evidence of a general belief in his time that Nero had set fire to Rome. (Barrett, pp. 122f)

So far the evidence for Nero starting the fire is pretty thin. Indeed, as Barrett points out,

the first explicit and documented claim that Nero was responsible for the fire is made no earlier than the final years of Domitian’s reign (he died in AD 96), in the line of the Silvae of Statius, quoted above, about the flames of the guilty tyrant ranging over Rome’s heights. (p. 123 — bolded highlighting in all quotations is mine)

So the record shows us that

there was a common belief by the end of the first century that Nero had been responsible for the fire.

And it was after that time that the historians we rely upon for the fire — Tacitus, Suetonius, and Dio — wrote their works.

–o0o–

Loved and Hated

But what was Nero’s standing like before and in the immediate aftermath of the fire among the different sectors of Roman society?

Here is Barrett’s summary of the “before”:

Before AD 64, Nero’s position seems to have been virtually unassailable. He had committed some unquestionably outrageous acts, like the murder of his mother, but the outrageous murder of a mother can be weathered when the son is immensely popular and the mother deeply unpopular, and when there are public relations experts like Seneca on hand to manage any potentially hostile reaction. (p. 223)

The majority of ordinary Roman citizens were “notorious” in the eyes of the “upper classes” for being easily won over by “bread and circuses”. Nero did not hold back on pagaentry-frilled spectacles and games. The “free grain” was halted for a time after the fire but apparently soon resumed. Evidence of Nero’s popularity, especially in the eastern part of the empire, is seen with the rise of several imposters claiming to be Nero and gathering followings after Nero had actually committed suicide.

The historian Suetonius speaks of a mixed reaction to news of Nero’s death:

He met his end in his thirty-second year on the anniversary of Octavia’s death, thereby provoking such great public joy that the common people ran throughout the city dressed in liberty caps. Yet there were also some who for a long time would decorate his tomb with spring and summer flowers, and would sometimes display on the rostra statues of him dressed in a toga or post his edicts as if he were still alive and would soon return to avenge himself on his enemies.

One of Nero’s successors, Otho, appealed to popular sentiment in favour of Nero:

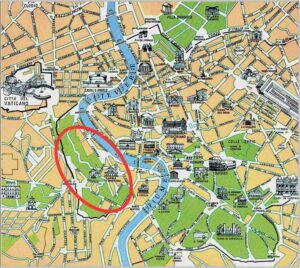

But when Otho . . . was greeted by the soldiers and ordinary citizens as “Nero Otho,” he welcomed the form of address, and, according to Suetonius, he may have used it in his earliest letters to the provincial governors. Otho also restored some of Nero’s statues, or at the very least turned a blind eye when others chose to set them up . . . and reappointed some of Nero’s old officials to their former posts. He also raised the question of special honors to Nero’s memory. One of Otho’s first acts as emperor was to allocate 50 million sestertii for further work on the Golden House [Nero’s famous post-fire architectural project]. Vitellius, who supplanted Otho, was perhaps not so overt in publicly respecting Nero’s memory, but even he carried out formal funerary rites to the late emperor in the Campus Martius, and during the banquet that followed he ordered musicians to perform Nero’s songs, and greeted them with enthusiastic applause. What Otho and Vitellius might have thought of Nero deep in their hearts is irrelevant. Their conduct shows that they had clearly decided it would be politically advantageous to present themselves as admirers of their supposedly infamous predecessor. All of this goes strongly against the idea that the great mass of the people resented Nero for the fire and for the building program that he initiated in its wake. It is surely significant that although Dio claims that some cursed Nero for starting the fire, he does admit that this is just an inference—Nero’s name did not in fact appear in the graffiti that began to materialize soon afterward. (pp. 224f)

Notice Tacitus’s description of how various social classes responded to the news of Nero’s death:

Although Nero’s death had at first been welcomed with outbursts of joy, it roused varying emotions. . . . The senators rejoiced and immediately made full use of their liberty, as was natural, for they had to do with a new emperor who was still absent. The leading members of the equestrian class were nearly as elated as the senators. The respectable part of the common people and those attached to the great houses, the clients and freedmen of those who had been condemned and driven into exile, were all roused to hope. The lowest classes, addicted to the circus and theatre, and with them the basest slaves, as well as those men who had wasted their property and, to their shame, were wont to depend on Nero’s bounty, were cast down and grasped at every rumour. (Tacitus, Histories 1.4)

Immediately after the passage setting out the horrors of Nero’s treatment of the Christians we read,

Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car. (Tacitus, Annals, 15.44.4)

It would appear, then, that Nero was not fearful that the public was turning against him in suspicion that he had started the fire, given such a display of mixing with them. Later in the Annals Tacitus informs us that conspirators were attempting to decide the most opportune time to slay Nero and one of the options considered was when he was making one of his public appearances.

Those who hated Nero the most in the wake of the fire were the wealthy, especially those who were being required to contribute “generously” to support Rome’s rebuilding. These well-to-do appear to have been most incensed over what they considered to be Nero’s “vanity projects” such as the Golden House as the purpose of the financial demands being imposed upon them.

Vespasian, Nero’s eventual successor, did replace some of Nero’s works in favour of building the Colosseum, a stadium for popular entertainment. Yet he also continued other projects of Nero, such as, it appears, the giant statue, the colossus.

The focus so far has been on the reaction of the people at large to the fire, and it is suggested here that the masses may not have turned against Nero at the time. This might explain the curious scheme described by Suetonius, in which shortly before his death Nero planned to bypass the senate and go directly to the popular assembly to plead his case. The speech that he prepared for the occasion reputedly was later found in his desk. It was believed that he abandoned the plan from fear of assassination. The Greek philosopher Dio Chrysostom writing almost certainly during the reign of Domitian recounts the view that Nero’s subjects would have been happy to see him rule forever, and everybody wished that he was still alive.(Barrett, p. 231)

Barrett’s view is that the wealthy classes were the ones who actively turned against Nero after the fire.

Nero’s egregious behavior in past years might not have impressed them [i.e. the ruling elite], they might at some level even have despised him. But provided his conduct did not affect their own careers or their own wealth, they seem to have been perfectly willing to tolerate it and to take the view that his antics had little impact on their own personal comfort and well-being. As a result of the fire, however, the upper classes, and in that number we have to include the wealthier members of the equestrian class, were affected personally and directly, since they were asked to dig deep into their pockets to subsidize the economic reconstruction. The rebuilding involved Nero in major expenditures and he was obliged to collect large sums from private individuals as well as from whole communities. Sometimes he was able to raise funds by voluntary contributions, but on occasion he had to use compulsion. Property owners who rented out their buildings found themselves seriously out of pocket, since for one year the rents for private houses and apartments were diverted to the emperor’s account. (p. 233)

Despite some difficulties, by and large, before 64 CE, Nero had little to seriously worry about from the senatorial classes.

This all changed in AD 64. And when it did, the resentful senators, and some equestrians, found common cause with the officers of the Praetorian guard. . . .

Whatever the reason, after the fire of AD 64, elements of the nobility, rich equestrians, and the Praetorian guard found common cause, and decided that Nero had to be removed. . . .

The relationship between Nero and the governing classes definitely changed from AD 64 on, and it is reasonable to interpret the growing tensions and hostility as one of the consequences of the Great Fire. (pp. 239, 245)

–o0o–