Followers of Richard Carrier’s blog will have known of Richard Carrier’s review earlier this month of A Shift in Time by Lena Einhorn:

Lena Einhorn on the Claudian Christ Theory

I am glad I did not mention it here at the time now because the page became more interesting in the following week with an exchange between Carrier and Einhorn. Lena Einhorn points out that she feels her “hypothesis itself is largely left unexplored” in Carrier’s review.

Lena further draws attention to the apparent irony of her work gaining attention by those who favour the Christ Myth theory since her own argument is that Jesus did exist, only not in the time setting found in the gospels and not as the sort of person portrayed in them either. This raises the problematic question of what we mean by “Jesus” whenever the question of his historicity surfaces. We need to have some idea of how to recognize the person we are looking for and the only guides to help us are the canonical gospels, yet we know the gospels portray a theological construct and not a historical figure! It is inevitable, therefore, that most people who look for the historical Jesus do look for someone resembling the mythical Jesus of the gospel narratives. Lena Einhorn breaks this circularity by identifying reasons to believe that the core events and persons found in the gospels match those of a couple of decades later according to the writings of the Jewish historian Josephus.

Carrier stresses his own conviction that the evidence is best explained without any need to postulate a historical Jesus at all. Einhorn replies:

The problem in comparing a hypothesis such as mine (“Jesus existed, albeit in another time, and this is the evidence”) with one suggesting he never existed, is that the latter is built largely on Evidence of absence. What I do in my book is line up evidence for his presence in the 50s (and for the New Testament as a historical text of the Jewish rebellion, lying hidden underneath a literary/devotional/supernatural narrative). It would have been a somewhat knotty exercise for me to challenge Evidence of presence with Evidence of absence (“what I just showed you never existed”).

She adds further explanation:

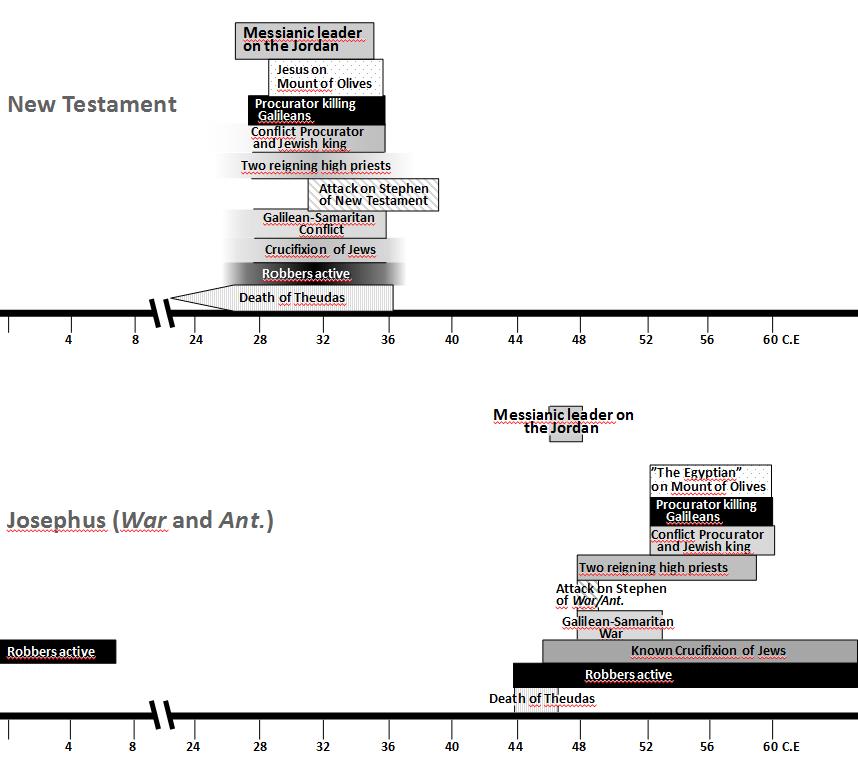

No, the time shift theory is not built only on the numerous similarities between Jesus and the messianic leader Josephus calls “the Egyptian” (the large following, the prophecy of the tearing down of the walls of Jerusalem, the betrayal to the authorities, the violent reaction of the authorities, the pivotal events on the Mount of Olives, previous time spent in Egypt, and in the wilderness). It is built on a slew of additional parallels between the Gospels and Acts, on the one hand, and events Josephus places in the 40s and 50s CE:

*The activity of robbers, lestai

*Known crucifixions of Jews

*An insurrection (Mark 15:7; Luke 23:19)

*A messianic leader gathering people on the Jordan river, who is subsequently decapitated by the authorities

*An attack on a man named Stephanos (Stephen) on a road outside Jerusalem

*Two co-reigning high priests

*A conflict or war between Galileans and Samaritans, limited in time

*Galileans on their way to Jerusalem for the festivals being stopped in a Samaritan village (Luke 9:51-56)

*A conflict between the Roman procurator and the Jewish king (Luke 23:12)

*A Jewish king with a prominent and influential wife (Matthew 27:19)

*A procurator slaughtering Galileans (Luke 13:1)

*A procurator and a Jewish king sharing jurisdiction over Galilee (Luke 23:6-7)

*Likely noms de guerre such as “the Zealot”, “Boanerges”, “Bariona”, or “Iscariot”

*The death of Theudas (Acts 5:36)

*A messianic leader who had previously spent time in Egypt, and in the wilderness, who prophesies about tearing down the walls of Jerusalem, and who is defeated by the authorities on the Mount of Olives

The 20s and 30s are – not only according to Tacitus, but also according to Josephus – a period when no robbers, no crucifixions, and no Jewish messianic leaders are reported. To name only a few discrepancies.

But most of it is there in the late 40s and 50s.

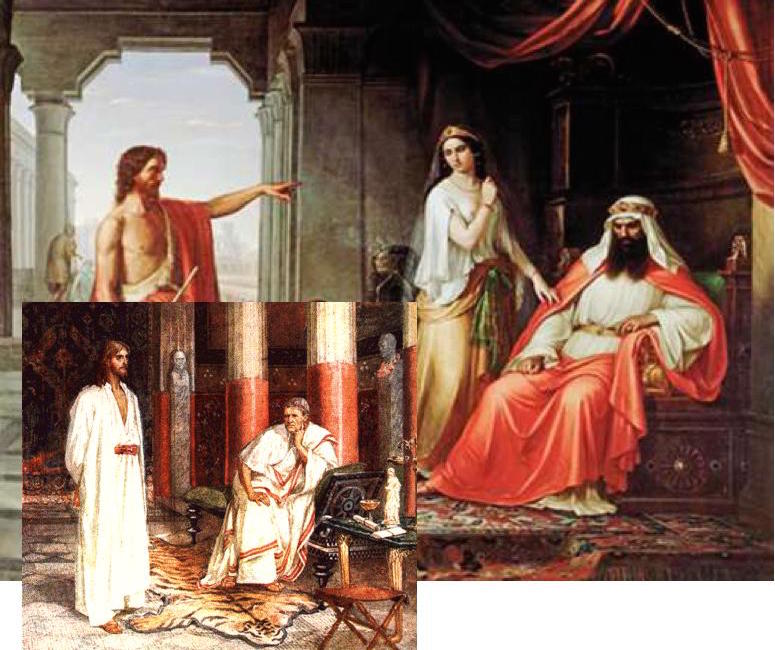

One of the illustrations Lena Einhorn posts in her reply to Richard Carrier:

Carrier subsequently responds to Einhorn’s argument that “the coincident character of the patterns” points to specific intent by the authors of the gospels. Continue reading “Richard Carrier & Lena Einhorn Discuss Shift in Time“