In 1823, the Supreme Court of the United States decided the case of Johnson v. M’Intosh (pronounced “Macintosh”). The case centered on a title dispute between two parties over land purchased in 1773 and 1775 from American Indian tribes north of the Ohio River. In the decision Chief Justice John Marshall outlined the Discovery Doctrine, explaining that the U.S. federal government had exclusive ownership of the lands previously held by the British. While the native inhabitants could claim the right to occupy the land, they did not hold the radical title to the land.

In plain English, the United States claimed ultimate sovereignty over the discovered territories, but permitted the native tribes residing there to continue to live in a kind of landlord-tenant relationship. Marshall explained that as a result, the natives could sell only their right to occupancy — their aboriginal title — and only to the federal government. With a stroke of the pen, American Indians had become tenants of the empty land.

Legal basis

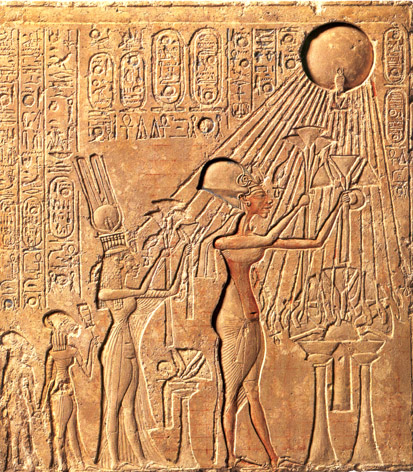

The case has several peculiarities; for example, Marshall’s decision did not rely on the Constitution or previous decisions, but instead upon international agreements put in place during the Reconquista of Iberia, and solidified shortly after Columbus’s first voyage to the New World. This framework essentially permitted Christian nations of Europe to invade, occupy, and colonize any non-Christian land anywhere in the world.

Marshall explained that the United States was the successor of radical title, which they had won by defeating the English. (The quoted paragraphs below come from the original text of the decision. The bold text is mine.)

No one of the powers of Europe gave its full assent to this principle [of discovery] more unequivocally than England. The documents upon this subject are ample and complete. So early as the year 1496, her monarch granted a commission to the Cabots to discover countries then unknown to Christian people and to take possession of them in the name of the King of England. Two years afterwards, Cabot proceeded on this voyage and discovered the continent of North America, along which he sailed as far south as Virginia. To this discovery the English trace their title.

In other words, as long as no other Christian nation had taken title of a non-Christian foreign territory, the English saw it as fair game. What Cabot had discovered, they reasoned, became the Crown’s sovereign holdings.

In this first effort made by the English government to acquire territory on this continent we perceive a complete recognition of the principle which has been mentioned. The right of discovery given by this commission is confined to countries “then unknown to all Christian people,” and of these countries Cabot was empowered to take possession in the name of the King of England. Thus asserting a right to take possession notwithstanding the occupancy of the natives, who were heathens, and at the same time admitting the prior title of any Christian people who may have made a previous discovery.

The same principle continued to be recognized. The charter granted to Sir Humphrey Gilbert in 1578 authorizes him to discover and take possession of such remote, heathen, and barbarous lands as were not actually possessed by any Christian prince or people. This charter was afterwards renewed to Sir Walter Raleigh in nearly the same terms.

While Marshall focused on so-called heathen people (usually construed as polytheists, animists, etc.), we should recall that Portugal operated under the same doctrine to colonize and subjugate people in Africa, some of whom were Muslims. Continue reading “The Doctrine of Discovery: The Legal Framework of Colonialism, Slavery, and Holy War”